Dr. Marie Rose Wong of Seattle University is one of our foremost chroniclers of life in the International District. Wong published last year a groundbreaking and exhaustive history of Seattle’s residential hotels (Building Tradition) and is working on an equally extensive work on prewar Japanese American baseball leagues that she hopes to finish by the end of the year. Doc Wong, as her friends call her, has served on and advised many nonprofit boards in the ID and elsewhere. With the Mariners headed to Tokyo in a few weeks to open the Major League Baseball season, we decided to talk with Doc Wong about America’s pastime as it was played before World War II in the International District. Excerpts of the interview follow.

How did you get interested in prewar Japanese American baseball?

It started with the interviews I was doing for Building Tradition. I can’t think of anybody in the Japanese American community who somehow or another didn’t start talking to me about baseball. I filed it in the back of my head, but I thought, this is coming up too much for it to be just an accident. When Building Tradition was coming to a close, I was spending more time gathering information about the teams in Seattle.

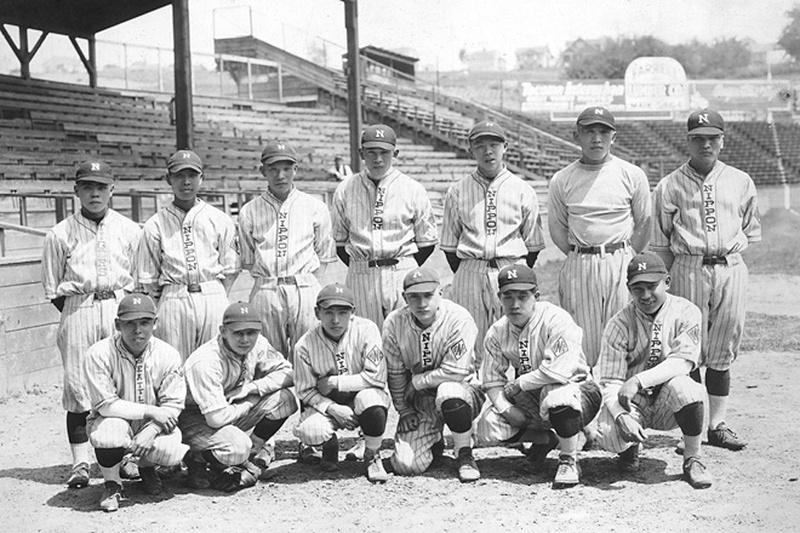

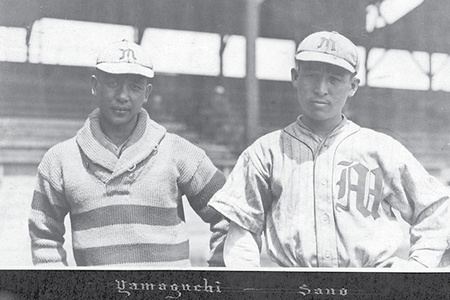

One of the families I interviewed was the Tokita family and Shokichi. His son, Kurt, is the board president of the JCCCW (Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Washington). He thought it would be a good idea for the Tomodachi Luncheon to make part of the focus baseball. They had a community event called Baseball is Bridges. We put out a call for anybody who had photographs or information on the community teams.

The really sweet thing about this is people started bringing in photographs from albums that survived the incarceration. I thought, wait a second, if people were only able to bring what they could carry, and they’re including these gigantic, heavy photo albums, it starts to tell you how important the game was to the families.

Right now, I have hundreds of photographs. Conservatively, hundreds. The JCCCW probably has thousands. The tough part is trying to find the stories behind the photographs.

How did you find the stories?

It’s really about getting out and talking with the community. The Main Street Gang (a group of close friends who used to gather for lunch and befriended Doc Wong) was hugely helpful. I also started talking with Mr. Kuniyuki, the grandfather of the owner of Kaname restaurant. Another person who has been very helpful – a sweet man and an incredibly good friend – is Tyrus Okada. He goes by the nickname Fish. Fish’s father (Ban) was basically in charge of all the managers who were in charge of all the individual teams.

What I am finding is there is a strong connection between the Issei and Nissei and the community newspapers. In fact, The Courier, which was published from 1928 to 1941, was responsible for getting all those teams into the Courier League. If it weren’t for James Sakamoto, who was the editor of The Courier, this may never have happened or have been as successful as it was.

Connected with that is The Pacific Citizen, which started one year after The Courier. The Pacific Citizen was where Bill Hasegawa and Joe Hamanaka of the Main Street Gang wrote. There’s this really strong connection between the power of the newspapers and what they were able to do for community development.

How many teams were there?

I’ve been counting up these teams, and every time I think I have them all, someone will say something, and I’ll think, oh no! You’re kidding? There’s another one. But so far, I’ve counted 48 teams in Seattle. That is just absolutely phenomenal! It’s amazing. The people who organized the teams never made any money – did it out of love for the game, love for the community, love for their families.

What I’m finding is that there would be four teams affiliated with one ball club. The teams were based on the skill and the age of the individual. It was possible for a young player who was really good to be part of a double-A team. There were also A, B, and C teams. It was a combination of assessment of age and skill.

Where did they play?

Literally, they would play in empty lots. They played in the street. They played in Liberty Field, Collins Field, Seward Park. There was one newspaper article I found that indicated that the mayor of Seattle threw out the first pitch at one of their tournaments.

Did they travel to play in other cities?

Primarily, they would play teams in the area. Green Lake would play White River. Tacoma had teams, Auburn, Fife, Kent, Bellevue, and a bevy of teams that were Seattle-based.

Players from Waseda University would come to Seattle and stay at the NP hotel. They would play local teams, and Fish said the Japanese players would always win. But the Japanese players would also show them techniques and train with them. It wasn’t rivalry; it was camaraderie, support.

The Asahi team of British Columbia is known as one of the best local teams that ever existed, but when you look at who was playing with the Asahis, you’re going to find that there were some Seattle guys. If the Asahi team was traveling, and they were short a couple of players in Vancouver, they would contact the Asahi team in Seattle, and a Seattle player would take the train up to play a game. It was a serious sport filled with fun. People say they did this to be recognized by the greater community, but the answer I got for the most part is they played because it was fun. They weren’t trying to get anything out of anybody. They did it because they loved the game,they were incredibly good at it, and it was fun.

One thing that your readers might find interesting is that there is a new Asahi team out of Vancouver right now that was playing in Japan. Transnational theory is big right now in looking at how people are connected. Baseball is the essence of transnational connection.

Interesting. Did the prewar games draw lots of spectators?

Yes. They had cheering squads of little kids. They sat in the first row for spectators. The Fourth of July games had a big turnout. People would come out. They would close their businesses or find other people to take over their business for the day so that they could have one day to watch the games. I get excited just thinking about it!

How close are you to finishing this project?

I don’t feel like I’m ready to call it quits. It’s an obsession. For anybody who does research, it is. It starts to take over every aspect of your existence. If you know there is still something out there to look at, like The Courier newspapers – I’m going through all of them – think that if I skip one, that’ll be the one that could have given me better insight. On Sunday afternoons, you can find me in Suzzallo Library (on the University of Washington campus) going through The Courier. I’d like to have a draft of the book done by the end of this year, and I think I’ll make it.

We know that baseball continued in the camps in World War II. Are you focused on that chapter as well?

I’m trying to get the prewar years. People have done studies through the war years. And after the war, the Nisei Vets sponsored a team. Baseball returned, but it never returned to the prewar levels. That’s not surprising,because any time you have some external force that starts fiddling around with community issues … community is never instant; it’s something that is nurtured over long periods of time.

What is it about baseball that made the connection with the Japanese American community?

Baseball was being played literally up and down the coast. The Japanese were aware of the game even before they emigrated to the United States. They were already playing it in Japan. They were well-versed in the sport long before they came to the United States.

It’s a little more challenging to figure out the stories because we’ve lost so many of the Niseis. But I gather what I can. And I’ve been very fortunate because the community is very dear. If I ask a Nisei to help me, I don’t know anyone who isn’t willing to help. I love this community, and I love finding out whatever I can.

* * * * *

Marie Wong is an associate professor of urban planning and Asian American community development at the Institute of Public Service and has an associate appointment in the Asian Studies Program and Public Affairs at Seattle University. She serves as an advisor for President of the Board of the Kong Yick Investment Corporation Company and is a board member for the Interim Community Development Association and Historic Seattle. She has written two books: Sweet Cakes, Long Journey: The China towns of Portland (University of Washington Press, 2004) and Building Tradition:Pan-Asian Seattle and Life in the Residential Hotels (Chin Music Press, 2018).

*This article was originally published on The North American Post on February 22, 2019.

© 2019 Bruce Rutledge