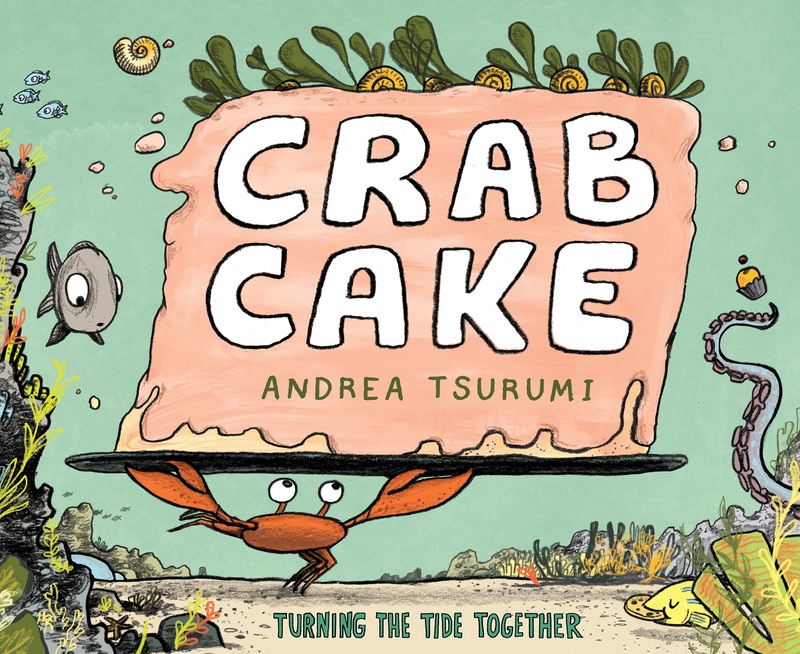

In the undersea world of Andrea Tsurumi’s new picture book, Crab Cake, the community has a steady rhythm: “ Seahorse pretends to be seaweed…Parrotfish crunches coral and poops sand…Pufferfish puffs up…And crab bakes cakes.” When a (human-caused) disaster brings this routine to a halt and all the animals into hiding, Crab takes action. What results is a warm-hearted affirmation of individual effort, art, and caretaking, with joyful, richly textured illustrations sure to inspire curiosity about ocean ecology, environmental responsibility, and the taste of mussel-topped cupcakes.

Tsurumi—who is also the author of picture book Accident! (about a chain of events set off by a clumsy, well-meaning armadillo) and comic book Why Would You Do That?—grew up as the child of professors in a suburb of New York City. Her work has also appeared in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Believer, and more. She spoke with me from her home in Philadelphia. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Mia Nakaji Monnier: What is it like making both picture books for kids and comics for adults? Are there certain things you can do in only one medium or the other? Are there any surprising overlaps?

Andrea Tsurumi: I kind of feel like I've always been doing the same thing. I've always been really interested in how images and text go together and how they tell stories, so that's been my go-to medium forever. But obviously there's a difference between comics and picture books—which gets funny sometimes when I explain to people who know me from my picture books who want to buy Why Would You Do That?, my comic book, just so you know, it is for adults, it's a much more adult sense of humor. It's kind of like how in kidlit, you have different grades, which is kind of nonsense because there are teenagers who read picture books and there are 8-year-olds who read YA, so your mileage may vary. But a picture book usually has a set number of pages and you can kind of accomplish one really cool idea in it. It's almost like a poem, right? Even if it’s a poem about farting dinosaurs. It's just a different expression of the same medium.

And it's always great to have those different voices that you're working with because it really gets me to connect with feelings I haven't thought about since I was a kid, since all kidlit authors are writing for the kids they used to be in addition to kids now. Feelings of frustration, for example. And with Crab Cake, I made a comic about this on my blog about why I made the book in the first place, but like a lot of people, I paid a bunch of attention to the news and was just feeling completely overwhelmed by all the horrible, brutal things that were happening around the world. And I remembered when I started doing the book that I had similar feelings when I was a kid—because being a kid, you feel constantly overwhelmed, right? Especially by stuff you don't understand and have very little power to engage with because you can't vote, can't drive, you don't really have any money of your own. When I was 12 or 13, I used to volunteer at a local nature center and be very concerned about ecology and animals, and I’d learn these realities, like, here's this beautiful, magnificent creature that is going to not exist in the future because we're screwing up its food chain. And then you begin to feel like no one else really cares about this or is talking about this, what can I do about it? And it just makes you quit. It wears you down over time and makes you feel like you shouldn't even try. Or that's how it happened for me. I might just be giving myself a pass—

Monnier: No, no. It's interesting that you talk about that in the context of childhood because when I read your book—I've been struggling with anxiety for a while, so I've been thinking about this a lot, how we sustain our energy and what to do with it. The way this crab is baking in the face of something horrible happening, it seemed like this really nice message that there is a point to doing what you do, whether you are an artist or whether you are just living your small life and contributing in small ways to a larger community that is all doing that to accomplish something larger. Is that something that you've dealt with as well, not necessarily clinically, but as an artist trying to figure out what is the purpose of doing your work?

Tsurumi: Oh, all the time. I read a really good book a year ago and I keep recommending it to all my artist friends because whenever artists hang out together, it's like a therapy circle opens. You really need to talk because you're doing a strange thing. You’re dealing with the capitalist side of art, and at the same time, it's also a psychological and emotional thing, and a craft thing. It's really lovely to talk with other people who get you and get this weird thing that you're doing. So this book is called Art and Fear, and it really lays out how being an artist is just dealing with uncertainty all the time, which is just the essence of what it is because being an artist—ugh, this sounds very Gwyneth Paltrow, but it is a verb, it's a thing we do, it's not a thing we are. So no matter if you're a Pulitzer-winning whatever or you're just starting out or you do this for yourself because it brings you joy, to engage in the activity is to be this thing or to do this thing. But when you're not doing it, you're like, well, then am I not an artist? It's interesting thinking in the context of this interview because a lot of figuring out or wrestling with cultural identity is also like dealing with uncertainty and contradictions, right? All the time.

Monnier: Absolutely. Can I ask you more about that? What is your background—are you Japanese on both sides of your family?

Tsurumi: No, my dad is Japanese. He was born in Kumamoto Prefecture in 1935, so he was there during the war as a child, and now he's a U.S. citizen. My mom was born in Queens, New York, and she's third-ish generation Ashkenazi Jewish.

Monnier: Is being mixed something you thought about when you were younger, or was there a point when you started thinking about it for the first time?

Tsurumi: It's always been something on my mind. I think it wouldn't have been if I were surrounded by 99.9% other people like me, but being on the East Coast especially, and being in an environment that's predominantly not that, it was absolutely there. I remember being in fifth grade, and I was walking down the hallway and a kindergartener looked up from the water fountain and just screamed, "Hi, Chinese girl!" and waved at me, and she was so happy. I was like, huh, that seems rude. But this was the early 90s, right around the recession in Japan, so I had a lot of friends who were Japanese or Korean or from other East Asian countries and I would hang out with them all the time. We kind of self-segregated a bit in elementary school. Not very consciously, but probably consciously in the way that kids form alliances, you know?

Monnier: They were people you could be comfortable around.

Tsurumi: Yeah.

Monnier: When you were growing up, was there a language barrier between you and your dad? Did you speak Japanese? Was he fluent in English your whole life?

Tsurumi: He speaks English, I don't speak Japanese—I studied it briefly in college of my own volition, but my parents decided not to teach my brother and me Japanese or enroll us in Japanese school when we were younger because they said they were concerned about us getting mixed up between learning English and learning Japanese.

Monnier: That's exactly what my parents said.

Tsurumi: Really? Okay, I've never really understood that, though, because now you have all these people starting kids early.

Monnier: They say that it's good for your brain to grow up bilingual. Yeah, I know my mom said that it was because I was in Illinois at that age when I would have been starting those things, so there weren't resources nearby, and also, we were just surrounded by white people and she tells me that she wanted us to be really good at English so we would be just like any other American kids.

Tsurumi: Right. You want your kid to fit in. That's hard.

Monnier: Do you feel sad about that now, not growing up speaking Japanese?

Tsurumi: Yeah, there are a lot of things I feel sad about and have regrets about. I've only been to Japan once, when I was seven, and I really want to go back. I wish that I knew more about Japanese culture in general. Language is part of that because it opens your access to books. I just wish I knew more about my family in particular. I'm much more concerned about questions of identity surrounding my actual relatives than I am really about Japanese culture. But I'm pretty comfortable in my identity as myself and my identity as something that's not one thing. Do you watch The Good Place at all?

Monnier: Yeah, but I’m not caught up.

Tsurumi: Okay, this is not a spoiler, but at one point, one of Jason's friends, whose name is Pillboy, comes up with this crazy scheme to sell something that is both a body spray and an energy drink. And Michael asks, "So do you spray it or do you drink it?" and Pillboy says, "You both it!" I feel like both-ing it is my identity.

Monnier: I like that as a verb.

Tsurumi: Right? Yeah, both it! It is that, like being uncertain and being kind of fluid. Everything is a construct. Being American is a construct. So I feel very American in my uncertainty, and I feel like that's a very American thing, to try to figure out like, what is Asian American or what is Italian American or whatever in 2019?

© 2019 Mia Nakaji Monnier