In Part 6, I wrote about how Yoemon educated his eldest son, Atae, in Seattle. This part will focus on how Yoemon’s barbershop business led him to make a big leap forward in starting a hotel business.

From barbershop business to hotel business

After moving from Kamai, Yamaguchi Prefecture, to Seattle, Yoemon moved to Walla Walla and made his barbershop business a big success. For an even bigger leap, Yoemon was thinking about going back to Seattle and starting a hotel business as his next venture. Running a hotel was something that many Japanese people in Seattle dreamt of back then.

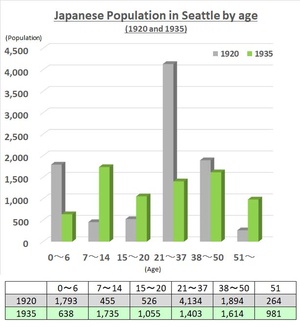

When he first moved to Seattle, Yoemon was planning to return to Japan once he earned a fortune. Yet as he called Atae back to Seattle and started living as a family with his wife and son, he started to think about settling down in Seattle. To do that, he had to take on a challenge bigger than a barbershop business and earn a steady income. His thinking was influenced by the change in the social environment of Seattle’s Japantown as well. In its early years, the Japanese labor force was made up of many young bachelors from Japan, but the immigration of such bachelors ceased in the late 1920s after the enforcement of the Immigration Act of 1924. On the other hand, America-born Nisei became an important part of the families of Issei immigrants who had taken picture brides. Toward the end of the 1920s when the economy was beginning to decline, more people were deciding to move back to Japan, and the Manchurian Incident of 1931 spurred the anti-Japanese optics, which further increased the number of people returning to Japan, making a significant drop in the number of Issei, especially those in their most productive years. The population structure of 1920 and 1935 shows this change.

This change in the social environment made an impact on businesses run by the Japanese in Seattle. In the barbering industry, the number of shops peaked in 1923 with a record number of 118, yet Japanese barbershops gradually began to close around 1926, and the number had dropped to 36 in 1935. A good number of owners quit their barbershop businesses and returned to Japan or switched over to other businesses. This change was seen not only in the barbering industry, but the number of businesses targeting the Japanese such as tailor shop businesses, ballparks, bathhouses, and Japanese diners also decreased. The hotel industry, however, was not part of this trend. As with the barbering industry, the hotel business had significantly grown by 1923, and the number of hotels peaked in 1926 with a record number of 191. The number remained steady after 1928.

Seattle was an international port, which connected Japan to the U.S. mainland via the shortest path, and it also served as an important transportation hub with a transcontinental railroad leading to Europe. Many tourists stayed there, making hotel businesses highly profitable. Seattle had many Japanese-run hotels and they were mainly for Japanese travelers at first; yet eventually their businesses thrived as hotels targeting Caucasians as well.

This is written in the papers and historical sources from back then, too. In an article published in Taihoku-nippo on February 10, 1911, titled “Hotels now and then,” it is noted that “Almost all hotels south of Yesler in Seattle are run by the Japanese. 80% of their guests are Caucasian, and all furniture items in the hotels are also provided by the Japanese.” According to Hokubei Nihonjin Soran (Compendium of the Japanese in North America), the hotels run by Japanese people around 1914 were mainly targeted at Caucasians, and the room rate was one dollar or 50 cents without meals. This is equivalent to around $10-$20 today. In the 1928 edition of Hokubei Nenkan (North American Almanac), it is noted that “In Seattle, there are nearly 200 hotels run by the Japanese, and their main guests are Caucasian. Their businesses are doing even better than their Caucasian peers.” As with barbershop businesses, hotels run by the Japanese also appealed to Caucasians. While Japanese barbershops gained popularity with the dexterity of Japanese women, Japanese hotels were appreciated by Caucasians for the cleanliness of the Japanese, as they would not leave lint in a room for the next guest.

As I have written in a previous part of this series, the profit rate of a hotel business was 40%, which was the fifth in the profit rate ranking of businesses run by the Japanese in Seattle, following 57% in barbershop businesses, 50% in clinics, 50% in fish retailers, and 44% in Daiuoku businesses (dry cleaners). But opening a hotel required a tremendous amount of money. The barbershop business required relatively little money to start and was profitable in the short term, yet the hotel business, while requiring much more money to invest in the beginning, had the possibility of turning into a business that is stable and profitable in the long term.

Yoemon makes leaps in his new hotel business

With the earnings from his barbershop business, Yoemon thought about starting a hotel business. While the barbershop business required perseverance in one’s work, as barbers had to stand all day long, running a hotel was relatively less demanding, with more administrative tasks and room management. Another difference was that people in the barbershop business had to work long hours, compared to those in the hotel business who worked irregular shifts including late-night ones. For his hotel business, Yoemon chose a busy, populated street in Seattle where many tourists would come, not Walla Walla. He did not have a doubt about this choice.

Japanese hotel owners in Seattle had established a “Hotel Association” in 1910. Yoemon, too, visited this association made up of Japanese hotel owners and learned about hotel management. According to the Taihoku-nippo in 1925, a general assembly meeting of the association was held on January 10 with about 80 attendees. Since then, the meeting was continuously held with more than 100 attendees regularly in January and in September. Yoemon was seemingly acquainted with Eihan Okiyama who was chairperson of this hotel association. Okiyama was vice-chairperson of the North American Japanese committee in 1928 and later became chairperson in 1930.

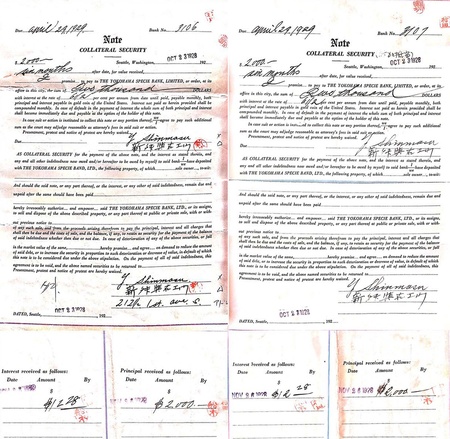

To purchase a hotel, Yoemon borrowed funds from the bank to compensate for the shortfall, to be added to the earnings from his barbershop business. Dated November 23, 1928, there were two documents of collateral security for $2,000 each equaling a total of $4,000 from Seattle Yokohama Bank. Yoemon’s handwritten note “Additional security” can be found, with his signature in the right center and the bottom right, and his seal was on one of them. On the back of this document, it was written that Yoemon received $4,000 on November 26 of the same year. The bank deemed Yoemon’s financial plan feasible and thus made a loan.

The average amount of investment in hotel businesses back then, according to some resources, was approximately $9,000. (About 19,000 Japanese yen back then and 20 million yen in the current rate) Assuming that the one that Yoemon bought cost $9,000, he needed about $5,000 of his own money in addition to the borrowed funds of $4,000, and apparently he had enough savings from his barbershop business to cover it.

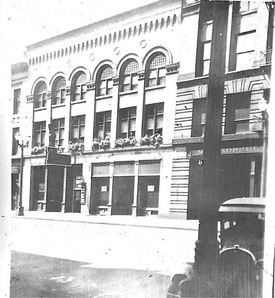

Thus Yoemon was able to purchase a hotel at the end of November 1928 on Occidental Avenue (written as “Occidental Avenue 311” on the photo) in Pioneer Square, a bustling area in Seattle. It was the moment of his dream coming true. I found a photo of the hotel taken by Atae around 1937. The hotel in the photo is presumably the one that Yoemon bought. It was a rather small hotel, a three-story, reinforced concrete building. In 1928, Yoemon moved his residence again from Walla Walla to Seattle and moved to the New Central Hotel in Japantown where he once resided.

Hotel management in Seattle was governed by the Revised Code of Washington, and the business had to be operated in accordance with the law, with security procedures such as installation of emergency exits and fire alarms. Thus hotel owners had to obtain a license conforming to the hotel code of the state of Washington. Yoemon studied until late every day and got the license. Despite the hardships forced upon him after moving to Seattle, Yoemon was full of joy and feeling a great sense of accomplishment, as he’d come so far, becoming a hotel owner.

While Yoemon continued to expand his business in Seattle, he was sending a great amount of money to his hometown in Yamaguchi Prefecture. In fact, he was thinking about rebuilding the old house in Kamai and having a big new house for his parents, siblings, and his two daughters.

References:

Edited by Junichi Torai, Hokubei Nihonjin Soran (Compendium of the Japanese in North America), Chuo-shobo, 1914.

Hokubei Nenkan (North American Almanac), Hokubei-jiji-sha, 1928 Edition

Kojiro Takeuchi, Beikoku seihokubu nihon iminshi (History of Japanese Immigrants in Northwestern America), Taihoku-nippo sha, 1929

*This series is a collaboration between Discover Nikkei and The North American Post, Seattle’s bilingual community newspaper. It is an excerpt from “Studies on Immigrants in Seattle – Thoughts on Yoemon Shinmasu’s Success of Barbershop Business,” the writer’s graduation thesis submitted at the Distance Learning Division at the Nihon University as a history major and has been edited for this publication. The Japanese version was published on November 26, 2019 on the The North American Post.

© 2019 Ikuo Shinmasu