As staff of the Collections Management and Access (CMA) department at the Japanese American National Museum, my colleagues and I make little rediscoveries in JANM’s permanent collection regularly. I refer to them as rediscoveries rather than discoveries since we’re certainly not the first to become well versed with the stories anchored to artifacts in the collection. These constant rediscoveries remind us that we arguably have the best job at JANM. It’s also one that comes with great responsibility since we’re tasked with the important job of ensuring the preservation of the collection for posterity.

Given the size of JANM’s permanent collection and the active collecting program that we maintain, we’re perpetually behind on cataloging and digitizing the artifacts, photographs, documents, artwork, and ephemera that comprise it. While this is a challenge inherent to all museums, JANM Collections Management and Access staff is making a concerted effort to document and digitize more of the collection to increase its accessibility. This work will enable our members and the public at-large to make rediscoveries of their own.

Often, this process begins with opening an archival box and sifting through the wondrous contents inside. One day, I came across a small grouping of historical materials that pertained to the wartime incarceration. This was not out of the ordinary, given that the World War II experience of Japanese Americans is one of the major strengths of JANM’s permanent collection. At first glance, this assemblage of artifacts—while unique—contained the types of materials that I had generally seen before. As I took a closer glance, though, I noticed the materials reflected the experiences of two generations of women of the Sasano family. This was rather atypical since women’s experiences are disproportionately underrepresented in most museums’ archival collections, including our own.

As I perused the items, noting the ways in which they revealed the experiences of an Issei mother and her two Nisei daughters during and after World War II, the value of this collection became readily apparent. This collection highlights the stories of the Sasano women—Taye, Frances, and Louise, the matriarch of the family and her two daughters, respectively—through the successes and challenges that characterized World War II and the postwar period.

An autograph book that belonged to younger daughter Louise, who was of junior high and high school age while at Amache, reveals the teenager’s personality through the reflections from her friends. Louise’s notebook, which contains the schoolwork she completed while at Amache, suggests that the incarcerees tried to maintain a sense of “normalcy” while detained in one of America’s concentration camps. Frances’ high school diploma from Amache helped her to obtain acceptance to college in Hartford, Connecticut. The various handbooks, yearbooks, and newspapers from Santa Anita and Amache help to reconstruct what daily life in the concentration camps entailed.

Finally, Taye Sasano’s study materials for her citizenship test, copy of the Bill of Rights, and naturalization certificate from the postwar period reflect Taye’s patriotism and love for her adopted country. Taye, despite the unjust detention that she endured during World War II, became a naturalized citizen after persons of Japanese ancestry were finally permitted in 1952.

Because the collection remained unprocessed since it arrived at the museum four years earlier, I wanted to confirm that the donor still intended for it to be accessioned into the museum’s permanent collection. I immediately called Scott Yoshida, the donor, and relayed my interest in the collection because it conveyed the experiences of three women of his family. He expressed his continued intent to donate the collection to JANM and asked if I would be interested in seeing a photograph of his mother, aunt, and grandmother—the three women highlighted in the historical materials.

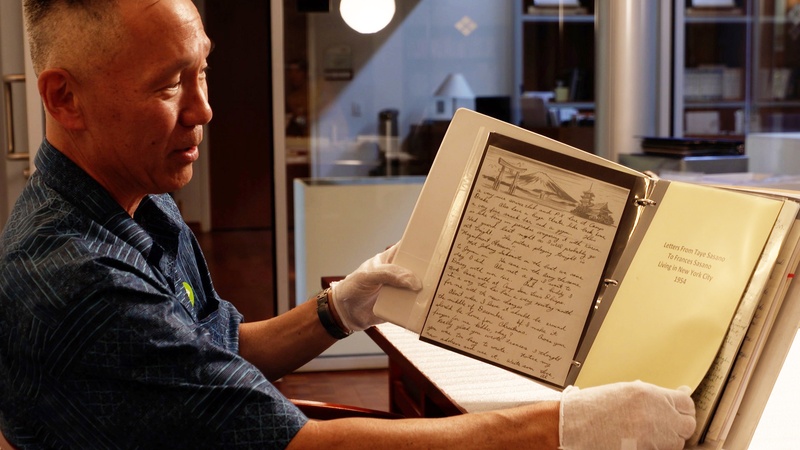

I assumed I would see a few family photographs upon Scott’s visit to JANM, but did not expect him to bring multiple boxes containing a couple hundred photographs, documents, ephemera, and 3D artifacts. Together, though, all of this material created rich portraits of the influential women in his family. He pulled out plastic Ziplog bags, which individually contained a small trinket or personal effects as well as binders containing photographs, historical documents, and ephemera each in a plastic sleeve. All of the items were meticulously labeled with an identification of the object, who it belonged to, and an approximate date of when it was created.

Scott proceeded to tell me more about his grandmother Taye, mother Louise, and his aunt Frances, using the artifacts that he brought with him to anchor charming, funny, heartbreaking, and inspiring anecdotes about each of them. He also introduced me to another impressive woman in his family, his great-aunt (his grandmother’s younger sister) Chiyoko.

Despite being of the same generation, sisters Taye and Chiyoko Sakamoto had different life experiences, which arguably originated from the difference in their citizenship status. Taye grew up just as American as her younger sister, yet because she had been born in Japan, she—like her parents—were considered aliens ineligible for citizenship. Class photos from Taye’s schools in Napa, California, show the diverse ethnic makeup of the agricultural-producing area in the 1910s and 1920s. Her high school graduation photograph from Polytechnic High School in Los Angeles reflects completion of 12 years in the American education system. Taye’s American-born sister Chiyoko, however, had more opportunities as a citizen. Her law school class ring is representative of her monumental accomplishment as the first Asian American woman to pass the California Bar Exam (1938) and subsequent career as a civil rights attorney.

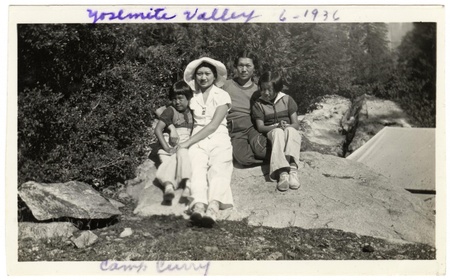

Meanwhile Taye married Yoshikichi Sasano, a Japanese immigrant who had spent the majority of his formative years in his native country of Japan. Together, the couple had three children: Frances, Louise, and Allen. Photographs, documents, and material culture artifacts in the collection document the Sasano family’s prewar life in Santa Maria, California.

In the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, life changed drastically for the Sasano family, just as it had for many other Japanese American families on the West Coast. Yoshikichi was taken by the FBI and incarcerated at the Tuna Canyon Detention Center in Los Angeles. With her husband gone and news of impending removal from the West Coast, Taye moved her three children, who were ages 15, 13, and 9, down to Los Angeles to meet Chiyoko in Los Angeles so they would not be separated during their relocation to Santa Anita Assembly Center.

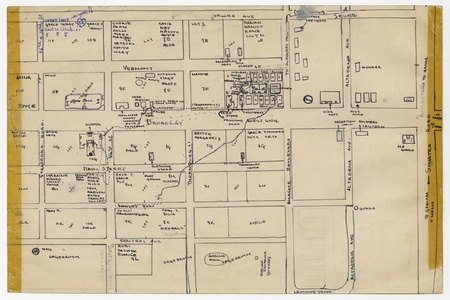

The collection consists of some of Louise’s prized possessions that she carried with her from Santa Maria to Los Angeles to Santa Anita to Granada (Amache). They include: a miniature steno pad with handwritten recipes; a charm bracelet that she continued to add to throughout her life to commemorate additional milestones; and a “Baby Dimples” doll. Additionally, there are mementos from her time at Santa Anita, including a drawing of the family’s barracks, a hand-drawn map of a section of the camp at Santa Anita that includes notations of where Louise’s friends lived, and announcements for social events.

Members of the Sakamoto and Sasano families were later relocated to Amache in Colorado, where they reunited with Yoshikichi. At Amache, Frances and Louise excelled in their studies at Amache Junior High and Amache High School. Chiyoko, while at Amache, served as legal counsel and provided guidance to residents.

Through Louise and Frances’s fastidious collecting, there are hundreds of documents and ephemera that capture daily life in Amache, including schoolwork, dance invitations, paper crafts made with innovative materials, flyers advertising social club activities, doodles, and notes from friends.

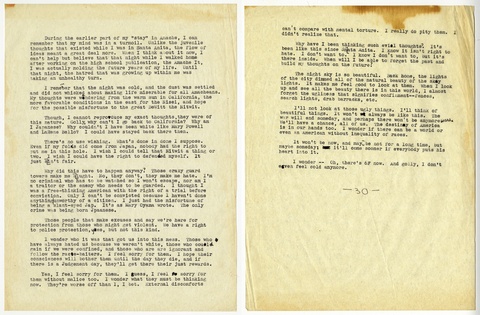

One of the most remarkable items in the collection is an essay that Frances wrote as a student at Amache High School, summarizing her thoughts on being incarcerated as a result of racial prejudice. In the essay, Frances notes that seeing the guard towers makes her hate. She articulates the internal consternation throughout her essay, remarking: “I’m no criminal who has to be watched so I won’t escape, nor am I a traitor or the enemy who needs to be guarded. I thought I was a free-thinking American with the right to a trial before conviction.”

Yet, by the end of the essay, she deliberately focuses on developing a more positive outlook: “when will I be able to forget the past and build my thoughts for the future... It won’t always be like this. The war will end someday, and perhaps there won’t be anymore (sic) wars. We’ll have a chance, all of us. The destiny of America is in our hands, too. I wonder if there can be a world or even an America [sic] without inequality of races.” To have this perspective at such a young age while incarcerated behind barbed wire is rather incredible.

The experiences of adolescent youth in camp, especially those of young women, is not adequately documented in our collections. The ephemera and mementos that Louise and Frances saved provide a glimpse into their day-to-day experiences and their inner thoughts. These materials juxtapose the fact that they were typical American teenagers who also had perceptive thoughts about racism and discrimination—the two major factors that led to their forced removal from their home on the West Coast and subsequent detention by their own government.

The collection also chronicles Taye, Chiyoko, Frances, and Louise’s experiences in the postwar period through the twilight of their lives, highlighting the challenges and triumphs that resulted. Taye and Yoshikichi divorced after the war, causing Taye to find employment to support herself and her children. She took up domestic work as her day job and studied at night to prepare for her citizenship test. Despite having lived in the United States for nearly all of her life, Taye finally became a citizen in 1954, soon after Issei became eligible for naturalization. The property tax records for the house that she was able to purchase, citizenship study materials, and naturalization certificate are reminders of the challenges that persisted after camp. They also demonstrate the incredible resilience and persistence required as the family returned to Los Angeles to rebuild their lives together.

After finishing school at Hartford Junior College in Connecticut, Frances returned home to Los Angeles and attended the University of Southern California (USC). She graduated in 1954 with a degree in social studies, and moved to New York City to work for the United Nations. Frances would later work for the Times-Mirror Company (now the Los Angeles Times), Metro Goldwyn Mayer (MGM) Studios, and other movie industry studios in audience research. Frances’ USC diploma and business cards are representative of her prominent career, which was foreshadowed from the promise she showed while at Amache High School.

While the early postwar period was difficult for Louise as she sometimes struggled to make ends meet, she persisted. Following graduation from Dorsey High School in Los Angeles in the spring of 1946, she took up typist and bookkeeping jobs. She married and had her son Scott. When her marriage did not work out a few years later, Louise took an offer from her mother and sister to move in with them. Louise’s son Scott grew up in a home, surrounded by several women who supported each other.

While each of these women was independent in her own way, each supported one another. Taye helped to maintain the household while Louise and Frances worked. Frances retired in 2001 to take care of Louise, suffering from colon cancer. After Louise passed, Frances moved into the postwar Los Angeles home to be closer to her nephew Scott and his family.

As Scott told me his stories of his grandmother, great-aunt, aunt, and mother, he acknowledged this history was incredibly significant to him, but he was surprised when I underscored their significance and historical agency in a broader context. Perhaps this is where “rediscovery” comes into play again. Seeing these women in a new light inspired Scott to revisit the family archive that he had in storage at his home. As he poured over the mementos in his collection, he viewed the artifacts in a different way and decided that JANM’s permanent collection would be the appropriate repository for these items.

Not only would they be accessible to his children and subsequent generations of his family, but they would also be available more broadly to others interested in the varied experiences of Japanese American women. This story of the Sakamoto-Sasano Collection is a testament to the power of objects and their ability to convey extraordinary stories of seemingly ordinary individuals. It is also representative of the aspect of our job in collections that provides the greatest satisfaction. As stewards of the Sakamoto-Sasano collection and those of many other families, my colleagues and I realize the importance of our work at JANM to ensure that these stories live on and remain relevant for many years to come.

* * * * *

Watch JANM’s video of Scott Yoshida’s visit to the museum. As he tells stories about his family’s artifacts, he shares how JANM collection staff’s “rediscovery” caused him to see the items in a new light.

Support the Japanese American National Museum’s ongoing work to document and share the Japanese American experience: janm.org/givenow.

© 2019 Kristen Hayashi