The artist Mine Okubo is most famous for her book, Citizen 13660, a graphic memoir of the Japanese American concentration camps. She became my hero while I was a student at University of California (UC), Riverside in 1979. As a young woman in my twenties, I felt inspired by Mine’s accomplishments as part of the “greatest generation” that survived World War II. She did it on her own terms and without apology. She persevered as a female artist and in life itself. The difficulties she experienced made her stronger. She retained her Nikkei identity and never forgot the Japanese American community or her beginnings in Riverside. It was exciting to discover a strong-willed young Japanese American artist who knew from an early age what she wanted to do with her life. During a time when women were expected to marry and raise a family, she decided that she would never let anything interfere with her art.

Mine was born in Riverside in 1912. She left the small community of Riverside for the larger world at UC Berkeley. At Berkeley, Mine was exposed to valuable experiences and interesting people that would shape both her life and her art. In 1938, a UC scholarship allowed her to travel to Europe before WWII. Her travels were cut short by the war, but not before she had traveled extensively for two years and discovered color and light in her paintings.

Growing up in Albuquerque, New Mexico, during the 1960’s, I was used to being the only Asian in a room. Our family were the only Asians on our block. In school, there were sometimes a few Chinese students but no Japanese Americans except for my brother and I. My parents moved to El Centro, California in 1970, when I started high school. I first learned about the Japanese American concentration camps in my high school California history class. This was briefly mentioned in a lone page in our textbook.

While Asian Americans in Los Angeles and San Francisco were discovering their identity with Yellow Power, I struggled to find mine in a conservative small town. Imperial Valley was a desert, both literally and culturally. The Japanese American farming community there was my first contact with my own community. I noticed the difference between my outspoken parents, who had grown up in Hawaii, and the mainland Japanese community.

After high school, I began independently reading books about the Japanese American concentration camps. I devoured Michi Weglyn’s book Years of Infamy which explained how U.S. government officials at the highest levels had been complicit in putting people into camps. It described how deeply Japanese Americans suffered during World War II because of the internment. I felt outraged by the stories of suffering and injustice.

When I needed to write a college paper for my Women & Culture humanities class, I wanted to find an artist who had been in camp. It was fortunate that I was a student at U.C. Riverside, because Mine had grown up in Riverside. She had donated papers and books to the Special Collections Library there. I found Mine’s book Citizen 13660 to be eye-opening because of her bluntly truthful black-and-white illustrations combined with matter-of-fact observations of daily life. Her comments were often humorous and sometimes poignant. While at Tanforan, she received letters from European friends telling her how lucky she was to be free and safe at home.

Mine’s work in Trek, the camp art and literary magazine at Topaz, later led to an offer to work for Fortune magazine in New York. She would reside in New York for the rest of her life. Citizen 13660 was originally published in 1946, right after the war. This was a daring book to publish at the time, when anti-Japanese sentiments were still high. When Citizen was reprinted in 1984, it won the American Book Award.

What amazed me about Mine’s art was that she never stopped exploring different art styles. Even after Citizen 13660 had brought her lifelong fame, she continued to evolve as an artist. Her later work included her “happy” paintings with bright colors and children, animals, or flowers as subject matter. She returned to Japanese folk traditions for inspiration, instead of European masters.

At the end of my class, I had to present my paper aloud. It was one of the few papers presented about a living female artist. The Special Collections Library had Mine’s New York address. With all the bravado of youth, I mailed her a copy of my paper with a letter.

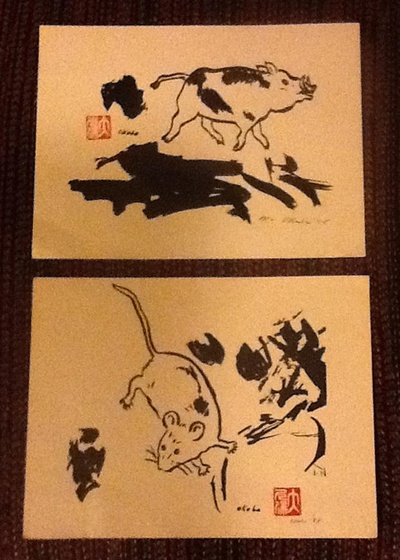

She began sending me her holiday cards printed with Chinese New Year animals in bold black-and-white prints. I was still writing her letters when I became active in the Japanese American community and their fight for redress/reparations. As years progressed, I eventually married and had a child. I continued writing her letters until her death in 2001.

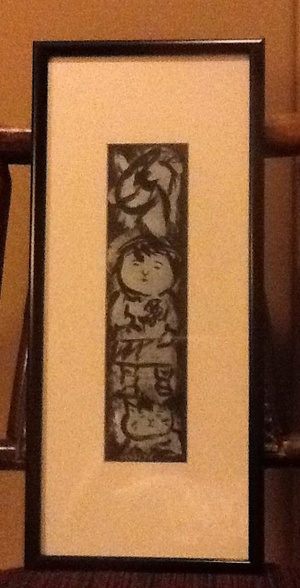

I will never forget the day in 1981 when a small package arrived in the mail from New York. I slowly unwrapped the brown paper package, wondering what Mine had sent me. As I pulled away the wrapping, I was amazed to discover a small painting inside. It was called “Sun, Girl, Cat,” a black and white acrylic in a playful style. Mine had included a short note. It read:

I am sending a little picture in appreciation of your thesis. I was impressed with your writing and the work shows you put lots of thought and effort into it.

Sincerely yours, Mine Okubo.

* * * * *

Our Editorial Committee selected this article as one of his favorite Nikkei Heroes: Trailblazers, Role Models, and Inspirations stories. Here is the comment.

Comment by Dan Kwong

Edna Horiuchi’s essay about Mine Okubo struck me on several levels: one, the importance of shedding new light on an extraordinary Nisei woman artist and her powerfully compelling creation, Citizen 13660; two, the journey of personal exploration undertaken by Edna herself; and three, the happy intersection of these two in the end. It was wonderful to read how one woman’s determination inspired the other, and reminds us that we never know how our creative efforts in life may impact someone, somewhere, someday.

Edna’s appreciation and respect for Mine’s choices as a female artist resonated strongly with me as I was raised by a Nisei mother, Momo Nagano, who also had to overcome the traditional expectations of (and limitations on) a woman in order to fulfill her desire to be an artist.

Both Mine’s and Edna’s stories are about women following a path of self-discovery and finding ways to share it with others - Mine Okubo through her art and writing, and Edna Horiuchi through her community activism. How perfect that they connected with each other.

© 2019 Edna Horiuchi