In Part 4, I shared how Yoemon’s Seattle-born children were left with Yoemon’s parents in Kamai and how Atae was brought back to Seattle where his parents were working. In this part, I will write about the pinnacle of Yoemon’s barbershop business.

From Seattle to Walla Walla

After calling over his eldest son Atae, from his hometown in May 1924, Yoemon lived in Seattle for a while and moved to the city of Walla Walla in the summer of the same year.

Yoemon’s family lived in a small hotel room in Seattle. Yoemon decided to move because he wanted to have a spacious house for his family. Though being a little far from Seattle, he was able to get a house of his own in Walla Walla, in the east part of Washington state.

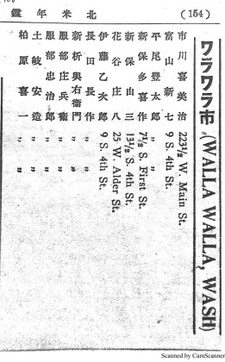

Walla Walla back in the days was a small town with a population of about 15,000. According to the 1928 edition of Hokubei nenkan (North American Almanac), the city of Walla Walla had 13 Japanese residents, including Yoemon. The almanac has names and addresses of the city residents, and Yoemon’s address—9 South. 4th St. Walla Walla, WASH—is listed there as well.

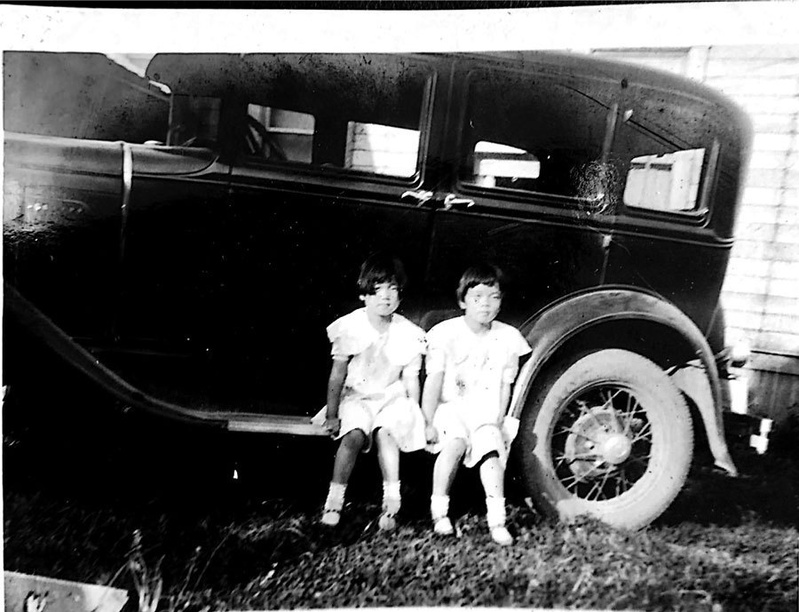

It took quite a long time to travel from Walla Walla to Seattle, but Yoemon was able to drive back and forth between the two cities as road improvements had just begun around that time. There is a photo of Yoemon’s car. It was a big car that could easily carry up to 4 or 5 people. Yoemon commuted to Seattle even after moving to Walla Walla and always found the time to see those who were significant in his life such as Chuzaburo Ito, his relatives, and friends.

For the Yoemon family, life in Walla Walla, which had clean air, was nothing but comfortable. There was a large open area around their house, which they turned into a flower garden. The place had a similar rural atmosphere to that of Kamai, and Yoemon felt at peace. Yoemon got to know another Japanese family in the neighborhood, and they became friends. I found a photo of Yoemon from this time, where he is sitting on the ground of the garden in front of his house. “In front of our happy house” was the note that was written on the photo.

The wife from the family Yoemon had become acquainted with was almost the same age as Yoemon’s wife Aki, and the two got along well. The family had a 6-year-old son and two girls aged 8 and 5. The boy made friends with Atae, and they played together. The two girls often visited Yoemon’s house. There are a couple of photos with the date when they were taken, September 25, written, which were meant to be given to the wife and each of the children. They were estimated to be from 1924, which was the first year for the Yoemon family in Walla Walla. This shows how close their relationship with the family was.

Yoemon took the two girls for drives and looked after them. He thought about his two daughters of almost the same age whom he’d left in Kamai, and felt a little sense of remorse. Yet there was no point in dwelling on it at that time.

Opening of a flamboyant barbershop

When Yoemon had just started his barbershop business in Seattle, he was taken to a barbershop owned by a Caucasian. At first, he thought he had entered the wrong shop. The roomy inside of the shop looked like a palace with gorgeous chairs, and the barber chairs were shiny, like one a king would sit in. The sight of the room stuck in Yoemon’s head, and he started to dream about having a luxurious barbershop like it.

With high rent in Seattle, it seemed impossible to make such a dream come true. Yet having moved to Walla Walla, Yoemon thought about making it happen. Seattle had a large population, and there were a lot of Japanese barbershops. In contrast, Walla Walla had a smaller population but no Japanese-owned barbershop. Yoemon wanted to run a barbershop that would attract the whole Caucasian population in Walla Walla. And to do that, he thought it would be absolutely necessary to have a big and lavish barbershop that they would all love. Yoemon looked for a potential place in Walla Walla, found one, and launched a project to open his dream barbershop.

According to the Great Northern Daily News of 1916, the average cost of opening a barbershop among Japanese owners was $590. Most of such Japanese barbershops were simple shops run by a couple with two barber chairs. It was noted that $1,200 to $1,300 were needed for a barbershop of the biggest kind.

Yoemon spent more money than that and completed his barbershop—which could possibly outdo the Caucasian-owned ones. It was completely different from the plain shops found in the dark underground of Seattle’s Nihonmachi. Yoemon’s spacious and ritzy barbershop had extravagant interior decorations with photos of celebrities (presumably) on the walls and big shiny barber chairs. He also hired more people.

As a result, his barbershop turned into a booming business. It attracted many Caucasians living in Walla Walla, not to mention the Japanese. The shop became more successful than the one he was running in Seattle, partly because Walla Walla didn’t have many barbershops. Caucasian customers loved the flamboyance of the big barber chairs and the shop’s interior as well as Aki’s deftness of hand. The shop became famous in Walla Walla.

There is a family photo of Yoemon, Aki, and Atae taken at this lavish barbershop. In the photo, Yoemon has a bright smile, and Aki and Atae, too, look very happy. I can feel a sense of satisfaction as they achieved a big goal.

As Yoemon achieved great success in his barbershop business, I wanted to find out how profitable the business was in general. In the “History of Japanese Immigrants in Northwestern America,” I found the “sales records of businesses in Seattle City” where they have detailed records of gross income and profit of 674 Japanese businesses in 21 categories as of the end of June, 1919.

As for barbershop businesses, the gross income of 54 shops in total was $227,150, and the profit was $129,750. Based on these numbers, I figured that the profit margin of a barbershop business was approximately 57%. Accordingly, the profit margin of other types of businesses was as follows: 50% for clinics, 50% for fish retailers, 44% for daiuoku business (meaning dry cleaners), 40% for hotels, and 37% for the shoe repair businesses. The average profit margin of 21 business categories was 20%. Of all the businesses run by the Japanese, barbershop businesses had the highest profit rate of 57%.

The high profit rate of barbershop businesses owed to a number of factors: opening of a shop did not require much money; working from early in the morning until late at night allowed them to take many Caucasian customers and make money, running shops with spouses helped keep the labor costs low, and so on. The success of Yoemon’s barbershop business was made possible by the perseverance fostered in rural life, which trained him to endure the hard work requiring him to stand all day long and the management of his business with Aki, who gave him diligent support.

Yoemon introduced in print

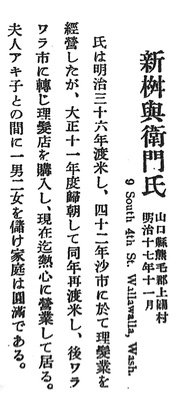

A note about Yoemon when his new barbershop business was thriving in Walla Walla can be found in the section “Directory of Japanese Residents in Northwestern America” in the History of Japanese Immigrants in Northwestern America, a 1,200- page record on the history of Japanese immigrants which was published by Taihoku-nipposha in July 1929.

“He moved to America in 1903 and started a barbershop business in Seattle in 1909. He went back home in 1922 and came to America for the second time in the same year. Later he moved to Walla Walla and bought a barbershop in which he runs his business to this day. He has a son and two daughters with his wife Aki, and the family lives happily.”

For Yoemon, who moved to Seattle from the rural countryside of Kamai with nothing, it was a great honor to be written about in the major historical work of immigration at the time.

However, Yoemon never knew about the publication of this book.

Yoemon worked his way up to make his barbershop business a great success and fulfilled one of his biggest lifetime goals. He was contemplating yet another big challenge as well. It was about how he could give an education to Atae whom he’d called over from Japan.

References:

Hokubei nenkan (North American Almanac), Hokubei-jijisha, 1928.

“Directory of Peer Businesses in Seattle” in Great Northern Daily News, April 1 to 5, 1916.

History of Japanese Immigrants in Northwestern America by Kojiro Takeuchi, Taihoku-nipposha, 1929.

*This series is a collaboration between Discover Nikkei and The North American Post, Seattle’s bilingual community newspaper. It is an excerpt from “Studies on Immigrants in Seattle – Thoughts on Yoemon Shinmasu’s Success of Barbershop Business,” the writer’s graduation thesis submitted at the Distance Learning Division at the Nihon University as a history major and has been edited for this publication. The Japanese version was published on September 30, 2019 on the The North American Post.

© 2019 Ikuo Shinmasu