The trials and tribulations of pre–World War II Japanese on the West Coast are well documented, but there was a small group of them that were uniquely special and nearly lost to obscurity. The adversity they faced was as unparallel as the historical significance of their community of El Dorado County, CA.

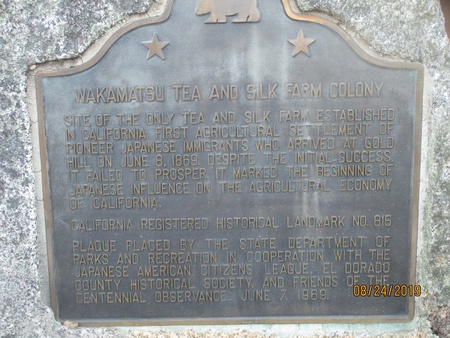

I’m a mixed race Sansei. My family decided in 1971 to leave southern California for the quieter rural El Dorado County in northern California three weeks before the school year ended. I clearly remember my first day at my new school. As the office gal took my parents, older brothers and I on a tour of the school grounds, the first place she took us was the parking lot behind the office and directed our attention to this big rock with a bronze plaque.

I recall her mentioning a young Japanese maiden name Okei who died nearby and two years earlier then Gov. Ronald Reagan came in to speak at the ceremony commemorating the plaque. That’s right, you guessed it; my new school unbeknownst to my family was Gold Trail Elementary forever associated with the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony, recognized as the first Japanese colony in the Continental United States. Years later I would come to realize that my family was the first Japanese family to attend Gold Trail and my mother was its first Japanese educator.

Fast forward, after American River Conservancy purchased the property in 2010 they began having a monthly open house during the summer months. With such personal ties to Wakamatsu, I started attending, gradually becoming more involved. Growing up in the area my family had numerous connections to early settling families, including several of the Veerkamps, the family that took in Okei and fellow colonist Matsunosuke “Matz” Sakurai. In 2016, I interviewed Harry Veerkamp, a friend’s father about Wakamatsu. In the midst of the interview, old Harry indignantly blurted out “You know there’s a lot more to the Japanese and Gold Hill than just Wakamatsu!” A bit stunned I replied “What?” and he repeated himself. It was then and there I realized that literally with the exception of Wakamatsu, the birthplace of Japanese American history has no Japanese American history to speak of. Why was that?

I sought out to learn why. Life growing up as Japanese in El Dorado County was not easy to say the least and could not image what it would have been like per-WWII. What I learned was fascinating but eerily similar. According to census records the Japanese population in the county at any given point never reached above 50, maybe as far as 1990 that I can determine. The 1930 census showed nine Japanese among two families. The 1940 census showed one family of four; Shinjiro Dote’s family.

Talking with old timers they expressed the same rationale of anti-Japanese sentiments prevalent throughout the West Coast at the time, yet counties still like Sacramento and Placer had thriving Japanese communities. A Kinoshita family descendant said to me that his Issei ancestor was told on numerous occasions by Placer County Issei he was crazy to live in El Dorado County, or that they would never allow their families to live there. In another conservation with Harry Veerkamp, he told me the county even tried to run his great grandfather Francis J. Veerkamp, who knew Okei and “Matz” personally, out of town for hiring Japanese around WWI. To provide the proper perspective the significance of this statement, trying to run a Veerkamp out of El Dorado County is akin to Martha’s Vineyard trying to run off a Kennedy.

Only the Dote family went to the internment camps, Poston, compared to the 1500 and 2200 individuals from the neighboring Placer County and Florin District; respectively. The Dotes for 25 years were the only Japanese family to truly call El Dorado County home and the oldest Japanese family until the mid 1980s. They chose not to return to El Dorado County after the war and no Japanese are known there until 1960. Son Shinji Dote was elected to the Bunka Hall of Fame in 2006 and daughter Grace would work as Head Librarian for Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics at UC Berkeley.

Other currently known El Dorado County Japanese of note: Tommy Hiroshi Kunishi; co-founder and long time owner of Sacramento Tofu Company. Dr. Sam Jiro Kimura; served as the Medical Officer for the 522nd Heavy Artillery during the war retiring at the rank of Major. After the war, he studied Ophthalmology at UC San Francisco from 1946-1949 and later served on the Atomic Bomb Causality Commission in Nagasaki as a researcher from 1949-1950. The Kimura Laboratory of Clinical Investigation at the University of California, San Francisco was so named in his honor. Sam has been mentioned in Fire for Effect - A Unit History of the 522 Field Artillery Battalion as well as numerous books regarding Ophthalmology and research. Other 442nd veterans include Placerville natives George Hidenobu Kinoshita and Eli Kitade, 1920 resident Paul Hideo Yokoi plus the brothers Sanai Joe and Frank Kageta whose father worked in the county (1910) before he had a family.

Numerous El Dorado County families from pre-WWII to pioneering, adamantly have said this story needs to be told, a story I’m still learning. They quietly admired the grit and determination of these Japanese to be so bold to settle were others sought not to in the place called the Japanese Plymouth Rock. This is why the family of Shinjiro Dote and fellow Japanese are my Nikkei heroes.

© 2019 Ryan Ford