“Golden Kola”, “with a national flavor” and that “combines with everything”, this is Inca Kola. He was born on January 18, 1935, when Lima (Peru) celebrated its quadricentennial and since then it has captivated Peruvians and foreigners. The story begins with Joseph Robinson Lindley, an English immigrant who opened his soda water factory “La Santa Rosa” in Rímac in 1910. By 1945, his youngest son Isaac took over management and with him a friendship with the Japanese community in Peru was born. .

ANTI-JAPANESE MEASURES IN PERU

With the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941), the United States went to war with Japan and then with Germany and Italy. Out of solidarity with the United States, the support of the American countries was sought by recommending that they break diplomatic relations with Japan, Germany and Italy at the III Meeting of Consultation of Foreign Ministers (Brazil, 1942). The first country to respond to the call was Peru, which broke all diplomatic and economic ties, declared war on Germany and Japan in February 1945 and even developed a fierce anti-Japanese policy.

Before the Second World War, there was already an anti-Japanese campaign in Peru, encouraged by certain politicians and the biased press who took a dim view of the massive Japanese immigration. Reflecting the times, restrictive laws were enacted that mainly affected Japanese immigrants, their families, and their economic activities in Peru, such as the closure of schools and institutions, the confiscation of their assets and property, and, finally, deportations.

In 1943, during the government of Manuel Prado, the “expropriation of property and rights of Axis subjects” was ordered, that is, the forced transfer of the businesses of Japanese, Italians and Germans. If a business was visited by an auditor, this meant its end: it would be inventoried and, finally, auctioned. The owner could no longer supply himself with new merchandise and only worked with what he had. When he sold something, he was able to keep a portion of the profit to subsist on and the rest was held in a bank for future government construction projects. If someone wanted to buy that business, they acquired it at a bargain price and the payment was also withheld. Meanwhile, the controller received a handsome salary, which was paid by the business owner. Because of this total control, large commercial houses went bankrupt. Small businesses were saved from suffering the same fate.

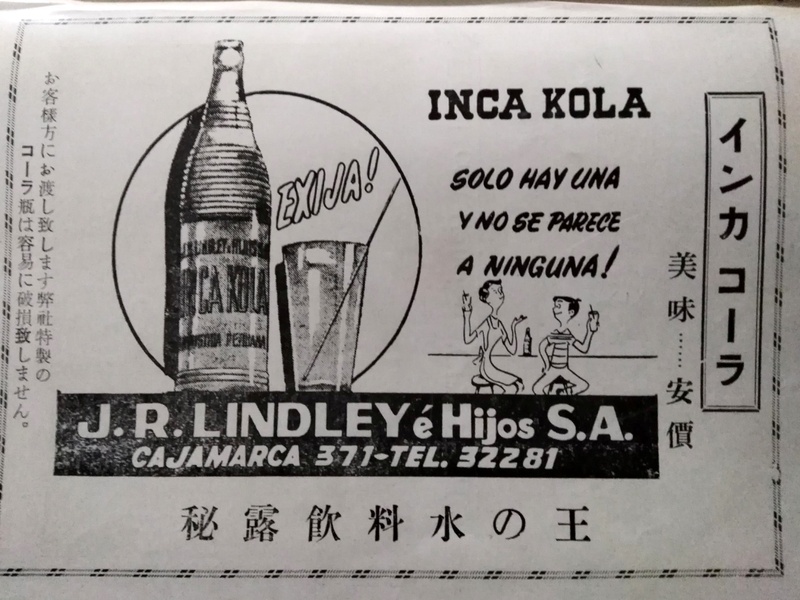

Those most affected by this policy were Japanese merchants. There was discrimination, abusive laws and even boycotts by the governments in power, which were sympathetic to the American politics of the time. Profits were decreasing and businesses were not as profitable as before, no one wanted to sell to them on credit anymore. There were even soda factories that did not want to sell their products to the Japanese. As a foreign memory, Giuliana Higuchi (blogger from La Liman Cosmopolitude ) repeats what she heard from family and friends of her parents: they all agreed that Coca-Cola closed its doors to Japanese merchants at that time. But their competition did show them a light on the way, golden and with a national flavor.

A HELP THAT WAS BORN AS A SALES STRATEGY

During the war, Inca Kola was the only brand that continued to supply the Japanese colony. Behind this help, we find the sales strategy of José, the eldest son of the Lindleys. When the Lindleys launched Inca Kola on the market in 1935, they wanted to popularize it using the best sales channels of that time: radio advertising, the busy restaurants on Capón Street (chifas) and the bodegas or grocery stores of the Chinese and Italians. .

In the prewar, the pulperías or wineries in Peru were managed mostly by Italians. When the Italians prospered and changed fields, they transferred their businesses to other emerging immigrants such as the Chinese and they in turn did the same with the Japanese. By the time Inka Cola was born, the most popular and numerous wineries were those of the Japanese. Even during the war and with Japan as a declared enemy of Peru, Isaac Lindley continued to supply Japanese businesses, being faithful to the original commercial strategy. Over time and thanks to Don Isaac, what this commercial strategy achieved was to strengthen ties of friendship between the Inca Kola and the Japanese community.

THE PREFERENCE THAT GOES BEYOND FLAVOR

There are memories that refuse to be forgotten. César Tsuneshige (former president of the Peruvian-Japanese Association) once said that Don Isaac Lindley, son of the creator of Inka Cola, used to go in his little truck to the stores of Japanese merchants to leave Inca Kola on credit ("fiado"). , at a time when others closed their doors to the Japanese. This is also confirmed by Giuliana: "My father said that he donated, I heard from others that he even donated soda. In a world where the Japanese were turned their backs , Mr. Lindley supported them.”

As a thank you, Inca Kola became an almost exclusive product within the colony, even after difficult times. The Inca Kola has been a must in all Nikkei celebrations and activities, such as weddings or undokais. According to the book Setogiwa: difficult times, by Carlos Yrigoyen, Inca Kola supported the community's celebrations, supplying them unlimitedly with its star product. For Isaac Lindley, the Inca Kola could not be missing in “all the community's festive celebrations in which the children participated,” as he says.

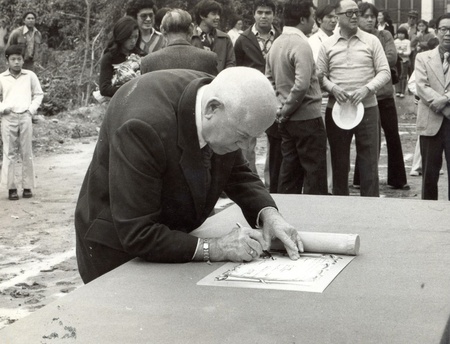

Don Isaac Lindley is also remembered with gratitude by the alumni of La Unión school. “He was the one who donated the first computers when they were still rare, at the end of 1983,” remembers David Uehara. While Diany Harada remembers him as the godfather of her class (1984). “And with great pride, it bears his name,” he adds.

And to accompany meals, Inca Kola is a must, because “it goes with everything,” even with chifa and Nikkei food. Humberto Sato, pioneer of Nikkei food and remembered chef and owner of Costanera 700, stated that there was nothing better than a clear drink like Inca Kola to digest the extreme flavors of his menu. As its slogan says, Inca Kola does go with everything.

With this perfect formula, which mixes business vision with social sensitivity, Inca Kola managed to position itself as a favorite in the Nikkei community. And with Don Isaac Lindley, this became a lasting friendship.

SOURCES:

Samuel Matsuda (2014), Walking 75 years along the roads of Peru.

Alejandro Sakuda (1999), The future was Peru.

Carlos Yrigoyen (1994), Setogiwa: difficult times.

Aldo Panfichi (2004), Interior worlds: Lima 1850-1950 .

Lindley Continental Ark (website).

Enterprise Power (magazine).

César Tsuneshigue for Nippon News (2014).

La Lima cosmopolidad (2009).

Marco Avilés and Daniel Titinger for Letras Libres (2005).

Jiritsu (blog).

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 116, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2019 Asociación Peruano Japonesa