Wakako Yamauchi, who died on August 16, 2018 at age 93, was a groundbreaking Japanese-American playwright and short story writer. Her first play, And the Soul Shall Dance, based on her eponymous 1964 short story, premiered at East West Players in Los Angeles in 1977. Soul launched her career as a playwright when she was already in her 50s. She went on to write many more plays, including 12-1-A, about her incarceration in the Poston, Arizona, internment camp during World War II. After the war, she married, raised a daughter, got divorced, and lived out the remainder of her life in her small, immaculately kept mid-century home in Gardena, California.

Yamauchi, who was a personal friend of mine, achieved her greatest renown as a playwright, but when relating an incident or articulating her thoughts, she always seemed to be speaking in prose, searching for the mot juste as she gestured broadly with upturned palms.

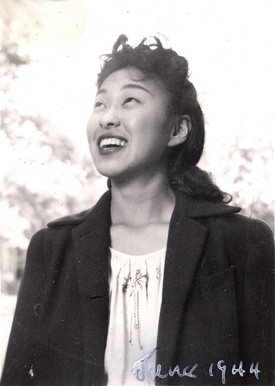

She was a thin, energetic woman with an oval face, a wide smile and eyes that effortlessly toggled between a mischievous delight and an expression of deep empathy. She was born Wakako Nakamura in the small town of Westmoreland (now Westmorland), socked between Brawley and the Salton Sea in California’s Imperial Valley. There was little “imperial” about life there, and the “valley” was part of the vast Sonoran Desert, flat and barren, its soil encrusted with white alkali, amenable to agriculture only through relentless irrigation.

Yamauchi’s parents, Yasaku and Hama, were Issei—that is, immigrants from a truly imperial land, Japan. They had left their homeland lured by the promise of prosperity and the chance to escape the stifling traditions that defined all aspects of life in the Shizuoka Prefecture southeast of Tokyo. What awaited them in California was the Alien Land Law, first enacted in 1913 and aimed expressly at the Japanese. It prohibited “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning agricultural land or leasing it long-term, thus relegating the Nakamuras to the peripatetic life of itinerant tenant farmers.

It was a harsh existence; perhaps that’s why Hama Nakamura always dreamed of growing wealthy enough to one day return to her homeland. Yamauchi, the third of the Nakamura children, gave her birthdate as October 25, 1924, but was ever quick to point out its inaccuracy, that owing to rural recordkeeping, and the fact that her parents couldn’t decide on her name, the actual date was days earlier.

The name they chose—“Wakako,” meaning “young child”—would prove fittingly straightforward for their down-to-earth daughter. Picked on by her elder sister and brother, Yamauchi was overjoyed, at age 12, when her mother gave birth to a fourth child, a boy who Yamauchi hoped would become her loyal companion. But five months later, her mother left the infant briefly alone in a washtub with just a few inches of water, and upon her return, discovered he had drowned.1 Wracked with guilt, Hama Nakamura might have taken her own life had not her three surviving children kept watch over her, making sure she understood how much they needed her. A psychic told the mother that the answer to her grief was another child, and she eventually gave birth to Yamauchi’s baby sister Kibo.

Yamauchi would recount to me that she and her siblings worked hard as kids—for example, covering the cantaloupe seedlings during the winter, after planting them in September. They used curved wire cages that they lined with wax paper, or sometimes two layers of sagebrush, sheets of newspaper in between, that they positioned at an angle sheltering the plants. Nothing was wasted; after winter passed, the paper had deteriorated, but they stored the sagebrush for the following year. When the weather was exceptionally cold, they lit bonfires on the periphery of the fields to generate heat and warming smoke.

Yamauchi would also say that the black, Chinese, Mexican and other children of color attended separate schools until the sixth grade, when they would be integrated into the mainstream (the Mexican kids having learned English by then). But the Japanese children went to school with the whites from the start, because Japan’s government had used its influence to insist that Nisei—the U.S.-born children of Japanese citizens—go to “American” schools. Nevertheless, when Yamauchi started school, she, too, scarcely spoke English, and had to deal with the disdain she faced from many of her white teachers and classmates.

Their houses were wooden shacks with dirt floors. I was living in Manhattan’s East Village when, in 1980, theater impresario Joseph Papp produced Yamauchi’s play The Music Lessons at his Public Theater in New York. Papp’s staff created an elaborate set featuring what looked like a well-constructed wooden cabin representing the home of an Issei farmer’s widow. When Yamauchi saw the set for the first time, she told Papp, “We didn’t live in houses like that.” Indeed, the Public’s reproduction of a Depression-era Japanese farmer’s dwelling in the Imperial Valley did not look like the kind of place that would be lit by kerosene lamp; where its occupants would drink water scooped from the nearby irrigation canals, after leaving it in containers for the silt to settle; that had no windows, only a tarp to cover the openings in winter (until they scraped together the money for a house with windows); or that could be shoved onto a truck when it came time every few years to move again. “Well,” Papp grumbled, “it’s built already,” and the set stayed as it was.

A providential double whammy—the 6.9 May 1940 El Centro earthquake and the failure of the annual lettuce harvest—was more than Yamauchi’s father could bear. He moved his family to Oceanside, north of San Diego, where Yamauchi’s mother got work first as a cook, then as the manager, at a boarding house for day workers on Santa Margarita Ranch, now part of Camp Pendleton. “That was a Japanese community before the war,” Yamauchi once wrote to me. “They called it Kumamoto-mura, for the prefecture they came from. They farmed on the crest of the hill and raised strawberries, string beans, flowers.”

Scarcely more than a year later, the life of every American changed, some more than others. Yamauchi was a high school senior when she returned home from a nearby movie theater to find her mother waiting at the front gate. “America and Japan are at war,” she said. Within a month, facing outright hostility from her fellow students and even some teachers, Yamauchi had to leave school.

And then, in February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 paved the way for internment of the Japanese. Once the evacuation orders were posted for each area, Japanese families, citizens included (and more than two-thirds of them were citizens), were given a week to gather whatever possessions they each could carry in a single valise and report to a designated assembly center. “Evacuation,” wrote Yamauchi in her 1988 essay American Dream, “was the euphemism for the incarceration.” In a 2006 letter, she described the start of her exile:

“I was a little over 17, had known racism most of my life, but who hasn’t? The civic and social studies classes told us we were equal, and in America, there is justice for all, but we knew, right?

As our train slowly pulled out of Oceanside, I looked out the window and saw a clump of weeds, still green from the spring rain but struggling to stay alive. I vowed to always remember that color. But things to remember multiply as we grow old and there isn’t room enough for everything.

Where were we going? What will happen to us? Starvation? Firing squads? There were people of all ages in that train: some old (40 up), some young like myself, plenty of children and babies. I thought, if they could take it, so can I, and at that point, I stopped stressing out. Or tried to.

We, from Oceanside, didn’t live in horse stalls. Our barracks were made of new lumber, still raw with knots cracking and jumping out. We closed the holes with tops of tin cans. Those few with money ordered sheets of dry wall (the ubiquitous Sears & Roebuck) and installed them. Maybe they were budding architects or more likely, blue-collar guys just practicing for when they would be free. The rest of us used the barrack 2x4s as shelves and set our pocket mirrors, combs, etc. on them and hung our clothes on nails and took two steps back, or right, or left, to our cots. No privacy. Well, most of us were family, anyway.

… even the lives of bottom feeders are moved and changed by the political pollution that filters down.”

In later years, resolute Nipponophile that she always was, Yamauchi would say that the Japanese, feeling threatened by the United States, were baited into attacking Pearl Harbor. She even justified the empire’s colonization of Manchuria: the Japanese, crowded onto a few islands, were forced to go elsewhere for resources, and, in any case, those areas were not being utilized to their full capacity. She may have had politically incorrect justifications for Japan, but she brooked none for America.

Poston, Arizona, in the Sonoran Desert a few miles from the California border, and about 130 miles from where Yamauchi grew up, averages triple-digit temperatures a third of the year, and hits near freezing in winter. The “Poston War Relocation Center,” the largest of the 10 internment camps, was an affront not only to Japanese Americans, but Native Americans as well; it was built on the Colorado River Indian Reservation, even though the tribal council wanted no part of this new increment to American racism (they were overruled by the army and the Bureau of Indian Affairs).

Constructed by Del “Sahara Hotel” Webb under a military contract, it had a peak population of 17,000, making it, at the time, the third-largest city in Arizona. Armed sentries and the foreboding desert beyond the gates ensured no one would try to escape.

“We lost everything in Oceanside but the two armloads we carried to camp,” wrote Yamauchi in American Dream. “The evening we arrived, my father squatted on the dusty barrack floor for a long time, shoulders hunched, arms folded, his head deep in shadow. I can see him now.”

It was in Poston that Yamauchi met, for the second time, lifelong friend and fellow writer Hisaye “Si” Yamamoto, whom she had unknowingly admired for years. They had previously encountered one another in Oceanside, but did not hit it off since Si was older and, as Yamauchi saw it, more worldly.

As it turned out, the diminutive Si was the anonymous author behind “Napoleon Sez,” a column in the Kashu Mainichi (the California Japanese Daily News) that chronicled the nitty gritty of daily life among the Japanese in California, including the simple foods they survived on, such as green tea rice (chazuke)and Japanese pickles (tsukemono).

Yamauchi had come to admire Si’s column while reading the back issues of Kashu Mainichi that she and her siblings had used to protect the seedlings back in the desert. Serendipitously, both women wound up on the staff of the Poston Chronicle, the camp paper—Yamauchi as a layout artist and occasional cartoonist, Si as a writer. The former was at first “disappointed” to learn the object of her veneration was a female, but this time, the two bonded, and Yamauchi would dutifully follow her friend about the camp as she walked her beat.

Yamauchi, who would fully explore her camp experience in her play 12-1-A (a discussion of which will follow in Part Four), was released on “short-term leave” from Poston in late 1942; she left the barb wire behind for toilsome work at a tomato-canning plant in wintry Provo, Utah.

When the work ended, she returned to Poston, and made the difficult decision to once again separate from her family by applying for, and being granted, “indefinite leave” to Chicago. Torn with guilt, but desperate to be free, she left for the Windy City, where, after a one-day stint at a shady firm producing marked playing cards, she joined the assembly line at the Curtiss Candy factory, where she spent nearly the rest of the war running a machine that made wrappers for Baby Ruths and Butterfingers.

Yamauchi relished her freedom, and passed many an afternoon at the Art Institute of Chicago, admiring its priceless collection. Her love of paintings had begun with black-and-white images of works by the landscape painter Camille Corot that she had encountered as a child. Now another passion arose in her—a love of live theater; she even attended one of the premiere, legendary performances of The Glass Menagerie, before it went to Broadway, with Laurette Taylor as Amanda Wingfield.

As the war was just about to end, she received word from her mother back in camp that her father, 12 years her mother’s elder and suffering from bleeding ulcers most likely linked to the copious homemade liquor he consumed during Prohibition, was gravely ill and vomiting blood. Yamauchi hurried to board a train back to Poston, praying during the agonizingly slow trip that she’d make it in time, only to arrive in the midst of her father’s wake. Even if the camps, by disrupting their lives so completely, had propelled the Nisei closer to the mainstream of American life, the price was steep for the many Issei who did not survive them.

Note:

1. Yamauchi wrote about her sibling’s death in her short story “Songs My Mother Taught Me”: “Waiting for my father that afternoon, my mother roamed from room to room, holding Kenji’s kimono to her cheek. We followed her everywhere. Outside the tub sat with its four inches of water and the toy boat listing, impervious to our tears.”

© 2019 Ross Levine