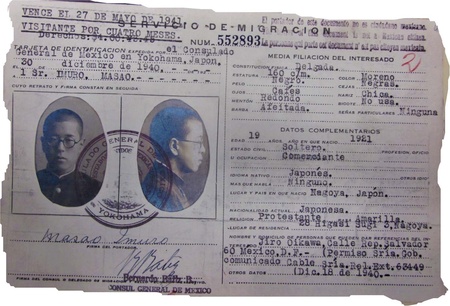

When I met Masao Iimuro personally, in 2007, I was already aware of many details of his life. He knew that he embarked for Mexico at the end of 1940, from the city of Nagoya, where he had been born 19 years before. He had precise details of his arrest in the month of May 1942 and his subsequent imprisonment in the Islas Marías prison, in Lecumberri and in the Perote fortress, in Veracruz. Without any trial or precise accusation and with the sole accusation of being a “dangerous foreigner”, the young Japanese was imprisoned for seven years until he was released in 1949.

Since their arrival in America at the beginning of the 20th century, in addition to being discriminated against, Japanese immigrants were, in fact, considered by sectors of the North American government as an “advance” of the imperial army, ready to invade the United States. For this reason, many years before the war between Japan and the United States broke out in 1941, American intelligence agencies monitored and persecuted them throughout the continent.

The confinement of 120 thousand Japanese and their descendants in concentration camps in the United States and the imprisonment of Iimuro were the violent and extreme proof of the war against Japanese immigrants in America. Hearing Iimuro's testimony firsthand therefore seemed very important to me to understand that stage in the history of Mexico. I looked for him and asked him to allow me to interview him but he flatly rejected it and told me that he did not want to talk about it. Fortunately for me, I asked a mutual friend, journalist Shozo Ogino, to request the interview again. Iimuro finally accepted, making it a condition that the meeting take place at the journalist's home.

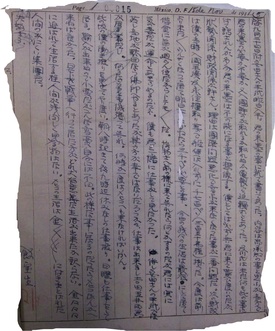

In the archives of Mexico and the United States I had collected extensive and detailed reports that the agents of the Ministry of the Interior and the North American FBI had on Iimuro. Even in the archives I found copies of the letters that young Iimuro sent to his friends and family in Japan. In his letters he urged them to be proud of being Japanese and expressed that he felt “very happy to be so.” But he also wrote something very delicate: “In a few days I will go out to shoot Roosevelt...then I will go to destroy the Panama Canal.” When Iimuro was arrested, he acknowledged the authorship of the letters and the seriousness of such statements, but told the authorities that they were evidently jokes that he could not live up to.

At Ogino's house, I handed over all the material that I had collected in archives to the then 87-year-old grandfather. Its voluminous nature was the first thing that surprised Iimuro. I even told him that there were reports from the director general of the FBI, Edgar Hoover, addressed to General Edwin Watson, President Roosevelt's secretary, so that he would be aware of the Iimuro case in Mexico. When the Japanese navy attacked the North American base of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Mexican government, at the request of the North American, forced the immigrants and their families, dispersed in many states of the Republic, to move and settle in the cities of Guadalajara. and Mexico. But Iimuro's imprisonment was extraordinary because the reason for doing so was based on the ideas and political position he expressed in his letters. The authorities thus considered him a “dangerous foreigner” of “fascist affiliation” for which article 33 of the Constitution was applied to him, which meant his expulsion from the country. The expulsion order could not be carried out due to the breakdown of communications with Japan, so it was decided to imprison him without any trial.

Before meeting Iimuro, the only image he could have of the young man was the one reflected in his letters. It was not difficult for me to imagine him—as he later confirmed to me—with his band around his head, hachimaki, shouting banzai to bid farewell to the Japanese troops heading to China. “Let's go Japanese boys, we will be brave warriors” was a verse from a song that Iimuro sang along with hundreds of students at the Nagoya train station. The letters showed the strong nationalist convictions of this young man and his support for the direction that Japan's expansionist policy had taken against the Western powers that occupied various Asian countries.

The life of Masao Iimuro, in fact, clearly reflects the ideas and vision of the young people who were educated in the 1930s at the height of the rise of the militarist wing that took control of the Japanese government and unleashed the intervention against China to from 1931. Therefore, through his personal history, we can reconstruct the situation of bitterness and confrontation between the great powers that dragged the entire world into a world war.

Iimuro found in Mexico a favorable environment to deepen his convictions against the United States. In 1941, the population was very aware of the North American military aggressions and interventions in Mexico. Three years earlier, in 1938, the government of General Lázaro Cárdenas recovered the natural wealth of the subsoil for the nation by expropriating the assets of the English and North American oil companies, a measure that unleashed an enormous wave of popular support.

The young Japanese confirmed this situation from what he wrote in his letters: “the people take the offenses of the English and Americans very highly” but he also felt supported by the Mexican population when he considered that “the masses are Japanophiles.” These popular sentiments, until then, were in tune with those of the Japanese population who considered the United States and England as evil devils, kichiku beiei, who had to be fought.

The extensive and instructive conversations that I subsequently had with Mr. Iimuro at his house allowed me to get to know in depth the young man who had arrived in Mexico. At first, I was able to realize the enormous shame that overwhelmed him for having written those letters and spending so many years in prison, facts that he kept secret even from his own family. The series of documents that he had given him were jealously kept in his safe so that no one could read them. With great discretion, although with enough confidence, the interviews turned into very enjoyable talks. Iimuro was recounting the events that marked that entire generation of young people in Japan, in particular the stage of “holy war”, seisan, with which Japan aggressively sought to “purify” the influence of Western powers in Asia for its own sake. benefit.

Iimuro's personal experiences allowed me to delve into the history of Japan during that time, thanks to the fact that he had an extraordinary memory and that he had a great knowledge of the history of his country due to the self-taught training that he acquired over time. As an interviewee, Masao Iimuro became a teacher for me, because any doubt I had about the pre-war period and about Japanese immigration to Mexico I came to his help to resolve it. His wife, Fumiko, was occasionally part of the talks about Japan at that time. Together they rebuilt the kurai tanima , or gloomy valley, a name with which the population remembers the long period of war that Japan experienced since 1931. Together we came to the conclusion that this valley extended its mantle to America due to racism and the persecution of the Japanese that the war hysteria generated.

I was able to understand the motivations of Iimuro who, without taking up arms, arrived in Mexico aware that his role was to support his homeland through the work he did with great efficiency at Porcelanas Kyoto, a company in which he began working at the age of 14. age in his native Nagoya. This company, a producer of tiles and ceramics, had expanded its sales to various Latin American countries with great success. The owner of the same, Shujiro Yasuda, entrusted an immigrant who lived in Mexico, Jiro Oikawa, to become the representative of that company and open a store on the important Madero street, in the center of Mexico City. Iimuro came to support Oikawa in managing it with such success that in a short time another branch was opened in a market in the Tacubaya neighborhood, where he worked until he was arrested.

Iimuro, upon being released four years after the war ended, with no resources, no job, no place to live, went in search of Mr. Oikawa. Together at first, they restarted their contacts with the owner of Porcelanas Kyoto who still maintained his company and was dedicated to the export of various products. Taking advantage of the period of accelerated growth of the Japanese economy, Iimuro went to Japan in 1954 to agree with Mr. Yasuda to restart a new company in Mexico. During this stay, Iimuro would marry Yasuda's daughter. It is interesting to remember that to travel to Japan, via Los Angeles, Iimuro had to go to the North American embassy to request his visa. The person in charge of the embassy sarcastically told him: “How are we going to guarantee the life of President Eisenhower? “Will we consult with Washington?” 1 Iimuro did not return, he traveled via Canada.

As the years went by, the company that Iimuro founded, Casa Yasuda , introduced Japanese sewing machines in Mexico that were sold with enormous success in several establishments; He later introduced Kenwood stereos. Until he was 80 years old, Iimuro continued working hard, closed the company and dedicated himself to reading from “a” to “z” the newspapers of Mexico and Japan and mystery novels, which he was passionate about.

Life gave Iimuro the time to enjoy his granddaughters and his two daughters who are successful professionals: one a doctor and the other an architect. Generous with what he had to live, Iimuro considered that perhaps he remained vigorous due to the seven years he was in prison. He remained that way until the last day of his life when he died peacefully at the age of 94.

The unjust imprisonment of Iimuro and the concentration of Japanese communities as a consequence of the war are facts that should never have been presented, much less repeated. The strength, work and organization of the immigrants made it possible to overcome this ordeal. An acknowledgment and apology from the government would be the least we should expect.

Note:

1. Shozo Ogino, I'll take care of Roosevelt. Memoirs of a political prisoner: Masao Iimuro, Artes Gráficas Panorama s/f. See also Sergio Hernández Galindo, The war against the Japanese in Mexico. Itaca Publishing House, 2011.

Author's note: I thank Joaquín Rosales for his valuable comments that improved this article.

© 2019 Sergio Hernández Galindo