Against the Brazilian military regime (1964-1985), which controlled freedom of speech with tanks and machine guns, young Japanese people took up the weapon of manga and fought for freedom of expression.

The three people who were honored on March 17th at the 35th anniversary of the Brazilian Cartoonists Association (Abrademi) were all affiliated with EDREL Publishing (Editora De Revistas E Livros). This publishing company was the first to publish Japanese-style manga in Brazil, and its core members were all second-generation Japanese people in their 20s at the time.

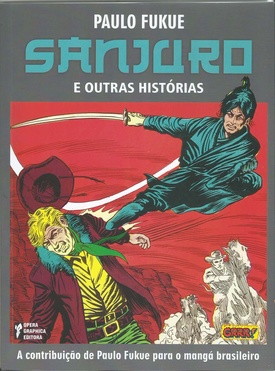

The only survivor, Yutaka Paulo Fukue (71), was selling the manga "Sanjuro" at the venue. "It was censored during the military government and was never published. I added my memories of that time and a message to myself and republished it," he said.

This manga was inspired by the film "Sanjuro" (directed by Akira Kurosawa, 1962) starring Toshiro Mifune, and is a fantastical tale of a ninja in a Western setting.

The atmosphere is closer to the unique western film "Red Sun" (directed by Terence Young, Paramount Pictures), which stars three of the world's biggest stars, Toshiro Mifune, Charles Bronson, and Alain Delon, than to the period drama "Sanjuro Tsubaki." However, the sword fighting scenes in the manga do have a "Sanjuro Tsubaki" feel to them.

One of the three honorees, the late Keiji Minami, was the manager of EDREL Publishing. He was born in Lins, a city in the state of São Paulo where many Japanese people live. His father subscribed to publications by the Cotia Industrial Association, which is how he learned about Osamu Tezuka. He became familiar with manga from an early age and began drawing it himself.

Minami came to São Paulo in 1965 at the age of 20 and published "Tupanzinho" through Pan Juvenil Publishing. This was an original work inspired by Tezuka Osamu's Astro Boy. He showed talent not only as a manga artist but also in business, becoming a co-investor and going independent two years later to start EDREL.

Minami then began discovering aspiring Japanese-American manga artists in their twenties, creating a monthly manga magazine as a venue for them to publish their works, and gradually capturing the hearts of readers.

Among the artists who emerged were Claudio Seto, Fernando Ikoma, and Paulo Fukue. Minami "gave these aspiring manga artists complete freedom to create as wildly as they wanted. This up-and-coming publisher created an era with radically original manga. Full of experimental designs, humor, existential dilemmas, and the cunning of youth, talented young people produced one manga after another, ushering in the golden age of Brazilian manga" (Sanjuro, p. 4). The "magazine" in question is a thin, pamphlet-like comic book called Gibi.

Young people who stood up against military rule with erotic comics

The military government disliked manga for its unique powers of vulgarity, eroticism, pornography, and violence. Perhaps they felt that the underground atmosphere inherent in subcultures could be connected to anti-government movements.

But Minami and his friends stuck to it. Claudio Seto's "Maria Erotica" was particularly famous. "There was a demand for erotic manga," Fukue reminisces. There is a strong image of Japanese Brazilians as "academically excellent and serious honor students." However, there were also "lovable bad boys" and "mischievous artists" like them.

However, eroticism was not as direct as it is today, and was only depicted in a suggestive way. It was still quite stimulating at the time. Erotic manga is also part of the freedom of expression, and while it was censored and banned many times, Minami and others continued to publish it, spending huge amounts of money on legal fees.

There is even a documentary about the struggle for comics publishing during this military era, A Guerra dos Gibis (The War of Comics Magazines), a short film made in 2012 by directors Rafael Terpin and Thiago Mendonça that has won seven awards.

Fukue testifies, "We were actually jailed at one point. Apparently the violent scenes of people standing up against those in power were reminiscent of anti-government activity or something. There are villains in every manga. It's easy to find fault with it, saying, 'It's a caricature of that General'. In fact, we once printed 40,000 or 50,000 copies and were just about to distribute them to bookstores, but they were suddenly confiscated by DOPS (the Political and Social Police, a kind of public order police). There were many times when we spent a huge amount on printing, and just when we were hoping to recoup our money by selling them, it all went to waste."

Furthermore, Fukue recalled, "Minami continued to publish manga while resisting the tyranny of such power. However, as this continued, business became increasingly difficult and he ended up giving up the publishing company." This was in 1971. Two years later, EDREL went bankrupt.

Around that time, Minami had started another publishing company, M&C, which was scheduled to publish "Sanjuro."

A magazine specializing in cult films is also available in the area of freedom of expression.

Interestingly, Minami published Close-Up, a magazine dedicated to films produced at Boca do Lixo, through M&C from 1974 to 1977. Details are given in the 2008 documentaryMinami em Close-Up: A Boca em Revista, directed by Thiago Mendonça.

This Bocca de Riccio is a part of the Centro district of São Paulo, where film distribution companies had been concentrated since before the war. From the mid-1960s to the early 1980s, during the military government, it became a gathering place for independent filmmakers. In terms of street names, it is around Triunfo Street in the Luz district.

The people who gathered here were all die-hard filmmakers who, in rebellion against the military government's restrictions on expression, dedicated their lives to making interesting films with little capital. One after another, cult films were produced that were full of vulgarity and violence, avant-garde, humorous, and sometimes decadent, but also packed with incredible ideas. Minami published a magazine that featured these filmmakers as protagonists and played an important role in informing the general public.

This movement was filled with the unique energy of young people, a rebellion against so-called traditions and authority.

For example, José Mojica Marins, nicknamed "Zé do Caixão (Zé of the Coffin)," is a prime example. He starred in and directed the masterpiece of Brazilian horror film, "À Meia-Noite Levarei Sua Alma (I Will Take Your Soul at Midnight)," released in 1964. Half a century later, in 2014, the film was chosen as one of the "100 Masterpieces of Brazilian Film" by the Brazilian Film Critics Association.

Another film released in 1972 was A Viúva Virgem (The Virgin Widow) (directed by Pedro Carlos Rovay, SyncroCine), which became a huge hit that year, attracting an audience of 2,635,962 people.

It is interesting that Japanese people were at the center of such cult films and subcultures. Moreover, young people of Japanese descent, who had a background in the pop culture of manga, played a part in driving independent Brazilian film culture.

However, when the ban on explicit pornographic material was lifted in 1980, Bocca de Riccio quickly withered away. Unfortunately, the area later became a gathering place for drug addicts known as "cracolândia," or "cracchi."

It was precisely because of the burden of the "military government's restrictions on expression" that I had to rack my brains to come up with creative ways to express myself, and as a result, I was able to create interesting works. Nowadays, it's easy to express yourself too directly... It's a strange contradiction that interesting works can be created because of restrictions.

"Sanjuro" was scheduled to be released in 1973, but was censored and banned. However, a young visitor who was flipping through the manga at the venue said, "Even now, I still don't understand why this was censored and couldn't be released."

© 2019 Masayuki Fukasawa