Editor’s Note:

The words and phrases used to describe Japanese American history vary considerably amongst scholars, government officials, and even those directly affected by Executive Order 9066: “relocations, “evacuation,” “incarceration,” “internment,” “concentration camp.” There is no general agreement about what is most accurate or fair. In 1994, a debate sparked around the issue of terminology when the Japanese American National Museum opened the exhibition, America’s Concentration Camps: Remembering the Japanese American Experience. When the exhibition traveled to Ellis Island, the American Jewish Committee, objected to the use of the term “concentration camps.” Some Holocaust survivors and their families felt it might confuse the public, who might conflate “concentration camps” with “death camps.”

Because of this debate, the National Council of the Japanese American Citizens League began work on the Power of Words Handbook. Completed in 2012, this guide set to bring about the use of accurate, non-euphemistic language to describe the Japanese American World War II experience and establish the preferred terminology that more accurately defines the terrible realities of this experience.

Please note the following chapter from The View From Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps, 1942-1945 was originally published in 1992 before the debate surrounding terminology. In this chapter, for example, the authors freely use the term “internment” as a synonym for the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. After the Japanese American Citizens League published, Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II “internment” was then used in reference to the detention of foreign nationals, as in the case of Issei who were swept up after Pearl Harbor and put in U.S. Justice Department camps.

* * * * *

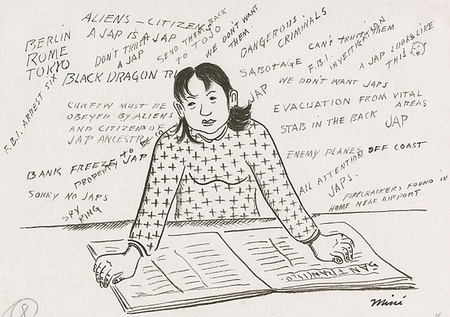

On February 19, 1942, two months after the outbreak of war between the United States and Japan, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the secretary of war and his military commanders to exclude persons from strategic military zones along the Pacific Coast, as well as the southern half of Arizona. Congress backed the executive order by passing a public law that subjected civilians who violated it to imprisonment and fines. The Western Defense Command under General John L. DeWitt issued more than one hundred orders that applied exclusively to the more than 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry in California, Washington, Oregon, and Arizona.

As a result, Japanese Americans were forced to abandon businesses, homes, farms, and their personal belongings. Under military guard they were first transported by trains and buses to a total of sixteen detention camps, euphemistically called “assembly centers,” most of which were located in California. Crudely built shacks and horse stables served as mass housing for tens of thousands. In the summer of 1942 inmates of the detention camps were removed to concentration camps in the interior, in some of the most desolate parts of California, Arizona, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas.

What led to this unprecedented action on the part of the United States government? How did Japanese Americans respond? What were the consequences for a society in which freedom and equality are constitutionally guaranteed? To answer these questions, we must go back to the beginnings of Japanese immigration to America.

THE EARLY YEARS

In Portland where four Japanese had found jobs as trackmen at Astoria for the southern Pacific Railroad . . . one evening considerable numbers of whites broke in, holding hunting rifles in their hands, and threatened the Japanese, “We’ll kill you if you don’t leave here within 30 minutes!”

— Kazuo Ito1

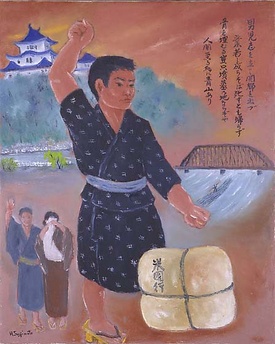

Tales of boundless economic opportunities lured the Issei, the immigrant generation, to the new land. On February 8, 1885, the ship City of Tokio arrived in Honolulu harbor with 944 immigrants on board. This was the beginning of officially sanctioned labor migration. From 1885 on, Japanese immigrants came to America in increasing numbers mainly from prefectures along Japan’s inland sea. By the time of the Immigration Act of 1924, which effectively barred further immigration, 200,000 Issei had settled in Hawaii and 180,000 in the continental United States.2 Additionally, some Issei from Hawaii migrated to the mainland. Initially most of the migrants were sojourners who intended to return to Japan with their “fortunes.” After their arrival the Issei worked hard as laborers in the fields, factories, forests, cities, and on the seas. They made vital contributions to the plantation economy in Hawaii, and to developing the western United States.

Although the Issei were reputed to be good workers, they were not docile under abusive conditions. The history of Issei militancy dates back to the beginning of the beginning of their labor contracts in Hawaii. Plantation workers rebelled under unbearable labor conditions. The Issei participated in two large organized strikes, in Hawaii in 1909 and 1920. On the mainland the Issei struck against the sugar beet owners in 1903. They were not alone in their protests. In the Oxnard, California 1903 strike and the Hawaii 1920 strike the Issei formed coalitions with Mexican and Filipino workers.

SETTLING IN

Immigrant records –

Now and then a bloody page

indicates the pain— Shunyo3

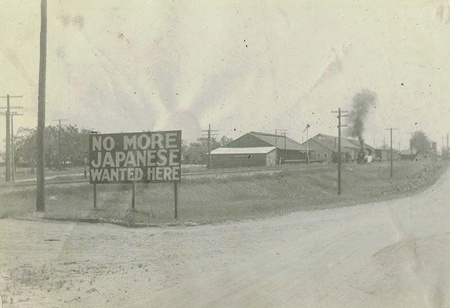

Although the Japanese made up only a fraction of the total population on the mainland United States, prejudice against them came from many quarters during the first decade of the twentieth century. Labor unions, followed by politicians, scholars, and political and civic organizations, agitated against them. Exclusion leagues were formed to lobby against further Japanese immigration. On October 1906 the San Francisco School Board expelled all Japanese American children from public schools and ordered them to join Chinese American students in a segregated school. Pressures by exclusionists led President Theodore Roosevelt to negotiate the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1908 with the Japanese government: in return for Japan’s voluntary restriction of emigration of laborers, Roosevelt promised to respect the rights of the Japanese nationals in America.

The Gentlemen’s Agreement stopped labor migration but allowed Issei to bring their wives and family members to America. The Japanese established families and communities. Exclusionists, reacting to this trend, agitated for a change in the laws. Banned from becoming naturalized citizens, the first generation Japanese became targets for further restrictions. The California Alien Land Law of 1913 forbade all “aliens ineligible to U.S. citizenship” to buy property or lease it for a period of more than three years. A revision of the law in 1920 made it illegal for the Issei to even lease land. Though they were not U.S. citizens, some of the Issei boldly went to court to challenge these discriminatory practices. Not surprisingly, these challenges were largely unsuccessful. In 1920, the Japanese government agreed to stop issuing visas to Japanese women. Abandoned by the Japanese government, the Issei resolved to fight on their own.

The Issei made repeated attempts to gain naturalized citizenship. In 1922, the Japanese Association found an ideal case in Takao Ozawa, a highly Americanized Issei, to challenge the Naturalization Act of 1790 which limited naturalization to free and “white” immigrants, thus making all Asian “aliens ineligible to citizenship.” The United States Supreme Court rejected Ozawa’s appeal, a bitter defeat that ended Issei hopes of becoming American citizens.

The Immigration Act of 1924 halted immigration by the Japanese and all other Asians. Exclusionary laws discriminating against Asians were not repealed until the latter part of this century.

CREATING COMMUNITIES

Issei’s common past-

Gritting of one’s teeth

Against exclusion— Kotoe4

Despite the hostile society which they encountered, Japanese Americans established communities in urban centers along the West Coast, forming links with farming communities. The Issei also engaged in wholesale-retail trade in vegetables, fruits, fish, and flowers and established independent businesses to serve their communities. They encouraged harmony and mutual aid within family and community. They promoted and taught their children, the Nisei, values such as mutual responsibility, respect for elders, and the value of hard work. Denied naturalization rights and land ownership, the Issei invested their hopes, dreams, and desires in the next generation. Issei immigrant parents promoted education and the Nisei worked hard in school. Nisei attempts to assimilate into the middle class society, however, were often stymied. Many college graduates could only find work on their parents’ farms and fruit stands. The Nisei were suspended between two worlds.

By the beginning of World War II the Japanese American community could no longer be considered a sojourner one, but had become a vital and dynamic community rooted in America. Despite their change of status from sojourners to settlers, however, Japanese Americans were still suspect in times of national crisis. The Federal Bureau of Investigation and army and naval intelligence began watching Japanese Americans in the early 1930s. Agents compiled records on community leaders and on those who appeared to have familial, religious, economic, or political ties to Japan. In Hawaii the military, aided by the FBI, began collecting intelligence reports on the Japanese as early as 1920s.

Notes:

1. Kazuo Ito, Issei: A History of Japanese Immigrants in North America (Seattle, 1974), 91.

2. Ronald Takaki, Strangers From a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans

(Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1989), 45.

3. Shunyo, in Ito, Issei, 105.

4. Kotoe, in Ito, Issei, 105.

*This article was originally appeared in the exhibition catalogue for The View From Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps, 1942-1945 in 1992, which was published in conjunction with the exhibition organized by the Japanese American National Museum, UCLA Wight Art Gallery, and the UCLA Asian American Studies Center at the Wight Art Gallery October 13 through December 6, 1992, to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of the Japanese American incarceration.

© 1992 Japanese American National Museum, the UCLA Wight Art Gallery, and the UCLA Asian American Studies Center