We called my Dad’s mom, Bachan. When we visited, she’d offer me a cherry-flavoured cough candy, and I would nod and say, arigato. Every Easter, she sent me and my brothers a chocolate bunny each. She didn’t speak much English and I didn’t speak much Japanese. So I knew her only a little. She was 4’7”, vegetarian, and raised eight kids. She lived 91 years smoking roll-your-own cigarettes. I’ve since realized her life reflects many of the most significant events in Japanese Canadian history.

She was born Taki Kinoshita on February 8, 1889 to Manzaburo Kinoshita (father) and Kuma Izumiya (mother) on Oshima Island in Yamaguchi prefecture. In that same year, Japan introduced a new constitution under the Meiji Emperor and established its first consulate in Canada, in Vancouver, where about 200 Japanese were living.

Bachan’s family owned various businesses, including vegetable oil refining, logging, shipping, and silk production. She was a sickly girl and had three maids to look after her, until she was about ten. After that, her father was not able to maintain the family’s business and their fortunes began to decline.

In her teens, Bachan went to Korea, to help her uncle run a taxi business. This may have been a side effect of Japan turning Korea into a reluctant protectorate after winning the war against Russian in 1905.

Meanwhile, more restrictive immigration policies in Hawaii and the west coast of the United States led to record high numbers of Asians arriving in British Columbia in 1907. An Anti-Asian riot rampaged through Chinatown and on to Powell Street, but were turned back by the undaunted Japanese Canadian community. Subsequently, Britain, which still controlled Canada’s foreign policy, negotiated a “gentlemen’s agreement” wherein Japan voluntarily began limiting the number of male Japanese emigrants to Canada. Women were exempt, which led to a rise in requests for “picture brides.”

Around then, Bachan received a marriage proposal from a farmer in Canada named Shinkichi Nakamura, who had been born in a village on the same island. He was one of many Japanese immigrants working together in cooperatives to grow strawberries, harvest, and distribute them. The photo he sent Bachan showed him in a Western-style suit standing next to a fine brick building, which Bachan supposed would be her future home. Unfortunately, she contracted malaria and the treatment led to hair loss, so the wedding was delayed a year.

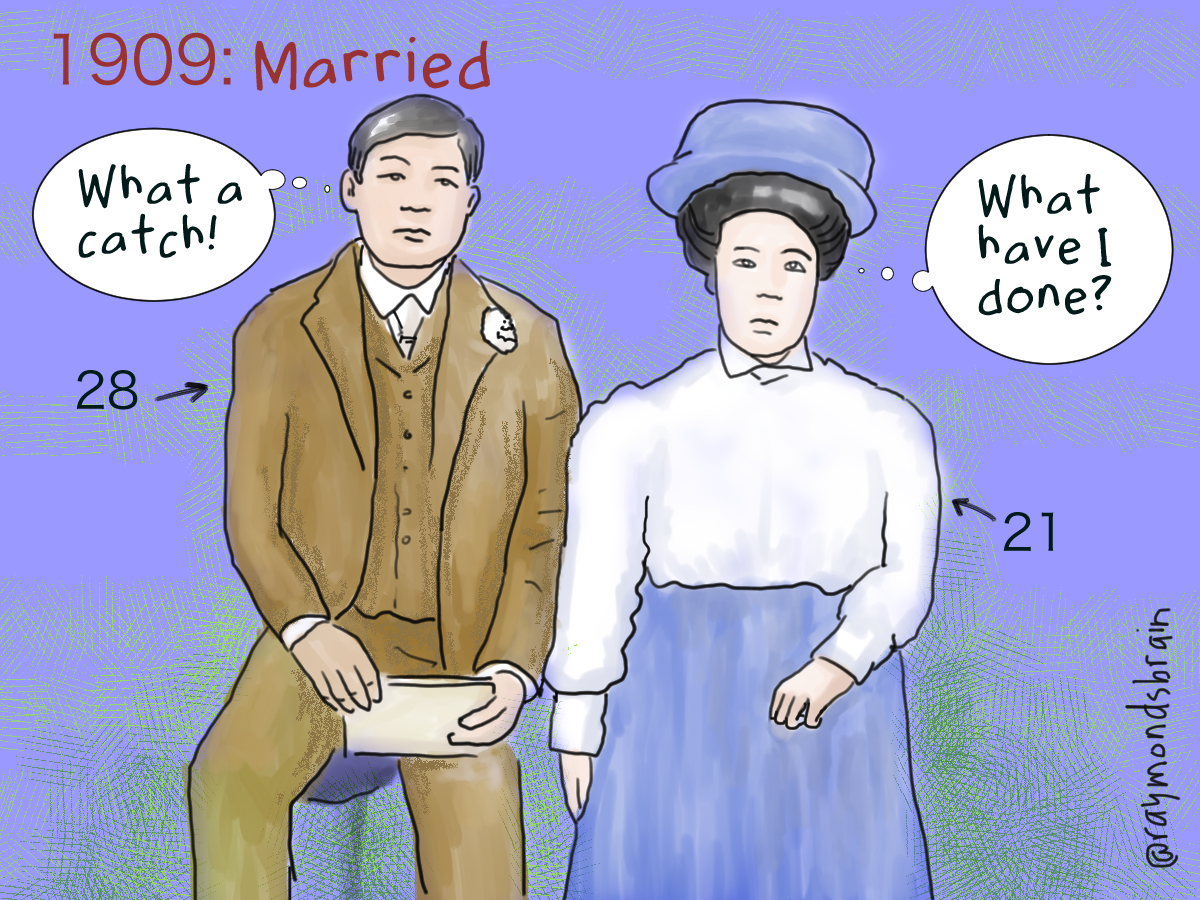

Finally, early in 1909, 21-year-old Bachan married 28-year-old Shinkichi, without having previously met in person. He drove them by horse and buggy to their home, not a brick mansion, but a wooden shack in the middle of nowhere (Port Hammond). It would burn down a year later with all their possessions. So they had to start over.

In 1919, my Bachan took her eldest son and two daughters to stay with her husband’s sister in Japan so they could be educated there, and perhaps as a form of long distance childcare. The sister, whose married name was Yanagihara, had a silk farm and used the children to cut mulberry for the silkworms and help sell the silk.

In 1924, Bachan and the rest of the family moved to Salt Spring Island to farm fruits and vegetables. The eldest son Shigeru, returned from Japan to help manage the farm. Bachan helped run the farm, looked after the eight children, as well as made and sold moonshine from their fruits. Shinkichi also worked in a mill and ran a laundry. In the mid 1930s, however, he became ill with throat cancer. He went back to his village in Japan, where he died in 1938.

The eldest son bought a dry cleaning business in Victoria to start a new life. He got married and they soon had a baby girl, but he still looked after Bachan and the youngest siblings. They all lived in an apartment behind the dry cleaning shop.

In the spring of 1941, RCMP began registering people of Japanese descent along the BC Coast. Each card included a photo, finger-print, and other personal details. They were identified as Japanese Nationals, Naturalized, or Canadian born, but in the end, all treated the same. Bachan had remained a Japanese National. Naturalized Japanese Canadians weren’t allowed to vote anyway.

After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7 1941, the United States declared War on Japan, and Canada followed suit. Soon the Canadian government began sending male Japanese Nationals to work on road camps in the interior of BC and across Canada. Those who protested this separation of families were sent to Prisoner of War camps in Ontario, along with leaders of the community.

The Canadian Government designated a 100-mile (160 km) “Protected Zone” along the BC coast, excluding all people of Japanese descent. The government set up the BC Security Commission to oversee the forced removal of around 20,000 people.

In April 1942, the BC Security Commission uprooted Bachan and others from Victoria to Hastings Park in Vancouver. Women like Bachan and their children were incarcerated in a former Livestock building, which still stank of animal wastes. They slept in wooden bunks lined up in rows, on mattresses stuffed with straw. Inmates hung sheets and blankets as an attempt at privacy. She stayed there for about four months. The Commission placed men in an arena, and teenaged boys in another separate exhibition building.

Most Nikkei, including Bachan were moved into the interior of BC. In the fall of 1942, she and her family took a train to the Slocan region to a relocation camp called Popoff.

Others went to work on sugar beet farms in the Prairies to keep their families. But the work was hard, the winters brutal, and the accommodations primitive, sometimes little more than converted chicken coops.

A small proportion used their own resources to keep families together in “self-supporting” camps that offered more independence.

Bachan and her five unmarried children, plus her eldest son and his wife and baby moved into one of the 14' x 28' shacks with two bedrooms and a shared kitchen with a wood stove. It had been built with green wood planks that shrank as they dried, leaving gaps between them and only a sheet of tarpaper for insulation.

They lived in these conditions for three years. Then they had to move either East of the Rockies or to Japan, which was called “repatriation” even though most of the children had never been there before.

In 1945, Bachan and her family arranged to go to Ontario to work for a large farm in Chatham that grew tobacco, sugar beets, and other crops. Even after Japan surrendered, people of Japanese descent weren’t allowed to return to BC. Bachan had nothing to return to and many others had their properties sold off by the Custodian of Enemy Property, without their consent.

In 1947, Bachan and her family moved to Toronto, where they heard offered more job opportunities. They moved to a house with her eldest son's growing family, as well as members of her daughter-in-law's family. Also that year, in response to changing public opinion, repatriation to Japan was halted as illegal, after sending more than 4000 people to the devastated country.

As others of Japanese descent moved to Toronto, they did not form neighbourhoods as they had in British Columbia, either to avoid making themselves easy targets again or as an effort to blend in. But they did form community organizations, such as the Japanese United Church, which Bachan enjoyed attending.

In 1948, Canadian citizens of Japanese ancestry were finally allowed to vote and in 1949, Japanese Canadians were allowed to return to BC. Bachan finally got her Canadian Citizenship in 1951. Life carried on.

In 1964, after extensive community fund-raising, the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre designed by Nikkei architect Raymond Moriyama opened in Don Mills with Prime Minister Lester B Pearson in attendance.

In 1977, Bachan turned 88 years old, a big year as the Japanese characters for those numbers resemble the character for rice, signifying abundance and good things. We had a big dinner with as many relatives together as possible. She had eight children, 35 grandchildren and 29 great grandchildren at the time.

By coincidence, 1977 was also the Japanese Canadian Centennial, marking a hundred years since the arrival of Manzo Nagano, considered the first Japanese settler. These celebrations, which included the first Powell Street Festival in Vancouver, led to an increased awareness within the Japanese Canadian community of Japanese Canadian history.

Bachan passed away in 1980, at 91. So, she did not witness the Redress settlement on September 22, 1988. After long and controversial negotiations between the Canadian government and the National Association of Japanese Canadians, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney made an official apology in the House of Commons, acknowledging the injustices committed during World War II. Survivors each received $21,000, and a Race Relations Board was established to avoid similar mistakes in the future.

© 2018 Raymond K. Nakamura