Forty five years ago, my father, Tatsuo Inouye, and I sat in the family kitchen to transcribe his Tule Lake Stockade Diary. My two little boys were sleeping in the back room while we cranked it out night after night in a smoky room until I had a paper for my class at UCLA.

It was not just an assignment; it is our family story, our voice, and our stamp on America.

As a Sansei born at the end of the incarceration, I am the first to say that I don’t have any memory of the camps. However, our family spoke of the camp in detail and seemed to have many artifacts. There was a large wooden plank that later much later I learned said, “Dai Ichi Dojo, Tule Lake. Stepping onto the crunchy ground in Tule Lake in November 1970 was emotional. It is where I was born and survived. It’s the place where I got a long scar on my neck because physician’s tools or attitude toward Japanese was poor. I am one of the lucky ones, I lived to tell.

During pilgrimages, I could feel the heat of Poston, the wind and dust of Manzanar, and the freezing cold of Tule Lake impacted me deeply. It pained me to think of the suffering my family had endured. Thereby, the story I share today is in honor of all who suffer injustice not only during World War II but all over the world that occurs to this day.

Let me start at the beginning. Tatsuo was ready to conquer the world leaving behind two brothers behind in Kumamoto, Japan. Older brother, Tokio, was already here a few years earlier so the risk would not be too great. He was full of Japanese ideals and American optimism, and his world was solid since he found work as an ice man, taught the Japanese language and Judo. He taught the farm boys how to defend themselves against high school bullies. He was tall in stature and held in high esteem by the small community he existed in. He even married the sweetest Sugimoto girl with a sunny smile.

EO9066 changed everything. He had to sell his “mom and pop” store on Folsom Street in Boyle Heights and leave his house in the hands of the Gomez family. They were his best customers who always paid their bills. They continued this practice by paying for the property tax for rent. Unlike those who burned Japanese items; he left judogis, books, and a Japanese flag that was signed by his brothers in the basement.

The war years were full of turmoil with the forced removal eastward to Lancaster to go as a family with the Sugimoto in laws. They were transported to Poston, Arizona along with thirteen hard working alfalfa farm families. They were assigned to block 19. It’s poetic that the Colorado River Indian Tribes are growing alfalfa today. Staying together was important.

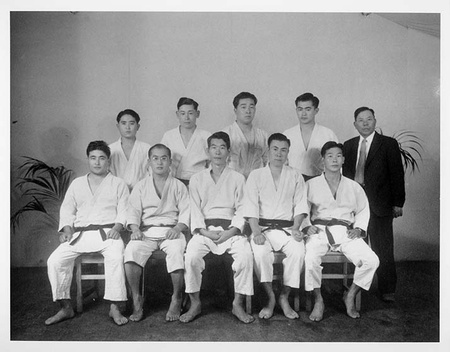

His new life in the scorching heat found a rhythm finally as he began to teach judo once again. He had no idea that he would be tested even further. He was well respected 4th degree black belt who conducted practice in Poston and Tule Lake. Since he was a person who was born in the United States that was educated in Japan, he had a heart wrenching struggle with the infamous loyalty questions 27 and 28. He responded “no, neutral.”

What will happen?

By the time he arrived in Tule Lake, Project Director, Ray Best, overreacted and ordered tanks and soldiers with bayonets. Six foot tall Inouye had begun judo practice near block 42 where there was space and one dim light. The pounding sound against straw mats and kiai must have been frightening. He was used to ukemi or falling a thousand times. He showed the others inmates how to do goho ate for exercise. For sure, it was threatening to the guards who knew little about the martial arts.

The authorities felt that he was dangerous so he was arrested after attending a negotiating committee meeting after the October farm truck accident. He arrived in Tule Lake when a terrible truck accident took place where five inmates were injured and one man died causing a strike calling for more safety. Tatsuo was 33 years old and locked up on November 14, 1943, while my mother, Yuriko (Sugimoto), who was 27 took care of two sickly children ages 4 and 7 alone in block 38 that was far away.

It’s time to appreciate the Tuleans who understood that protest was necessary. The racist Doctor Pedicord prevented good medical care in the hospital so many babies perished before they are born. Seeing the graves of the dead babies struck me hard. I felt lucky to be alive. Thus, it is my obligation to tell the story.

Food that was grown by the Japanese was stolen by unscrupulous profiteers including camp administrators who were caught stuck on the railroad with pork. It is not a surprise that violence and unrest would take place. The military tanks only accelerated the tension.

Tuleans have been scorned by its own community to this day. Studying our history and reading Tatsuo’s diary may change your perception of resistors and their sacrifices. Yes, the stockade was full of resisters but inside was a man who was compelled to tell the story for us to know.

Although my parents and sisters are gone, I feel their power. I hear them whispering in my ear to not to fear difficulties, to stand up for what I believe in, and to keep the descendants together. Today, I am their voice.

Now that the Tule Lake Stockade diary is moving forward with the force of wind, dust, the bitter cold felt in Tule, and searing heat of Poston, there is no telling what lessons can be learned from one man’s diary.

* Excerpts of the original diary that Tatsuo Inouye kept while imprisoned in the stockade at the Tule Lake Segregation Center can be found in “Tule Lake Stockade Diary” on the UCLA Suyama Project website.

© 2018 Nancy Kyoko Oda