Hachizo Nakamura, a Japanese immigrant who died at the age of 80, never forgot the help he received from Sentei Yaki. Since she met him, she used to celebrate two birthdays: one for her birth and another for her rebirth, which was the date on which she received Yaki's help. “Without his timely help, I would have died a long time ago,” he said.

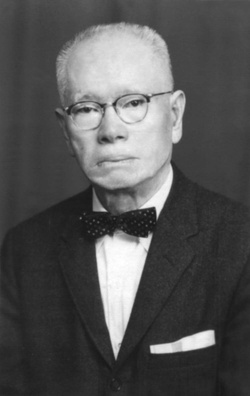

This testimony reminds us of what Sentei Yaki was like, a prominent Okinawan businessman, leader and philanthropist. Creator of the first Japanese association and promoter of tanomoshi in Peru, Yaki dedicated his life to helping others.

ADVENTURER AND ENTREPRENEUR

Sentei Yaki was born on Okinawa, in the city of Shuri (now Naha), on December 15, 1886 (according to other sources, December 9, 1884). Upon completing his studies at Waseda University in 1906, Yaki was hired by the Meiji Immigration Company. As supervisor of 65 Okinawan immigrants, Yaki arrived in Peru aboard the Kasato Maru in February 1907, on what would be the fourth voyage of Japanese immigrants to Peru and the first for the Meiji company. On this trip, Meiji brought 250 workers: 150 for the cotton and sugar estates on the coast and 100 for the rubber area of Tambopata in Madre de Dios.

Shortly after his arrival in Peru, Yaki realized that the salary he received from the Meiji company was insufficient to live adequately and therefore he accepted to work for a newspaper in Lima, the West Coast Leader .

Established in Lurín, he had a winery, a hotel and cotton crops. He also dedicated himself to raising pigs and, in Chanchamayo, growing coffee. In Lima, he was the first Japanese to open a winery, located on Aumente Street (current block 4 of Jr. Conde de Superunda). He also ventured into the Peruvian and Bolivian Amazon.

The rubber boom that ended badly

By 1910, in the midst of the rubber fever, Sentei Yaki received good references from the rubber area in northeastern Bolivia. He himself contacted the Inca Rubber Company and managed to convince 30 Okinawan immigrants to travel with him. Unlike the previous groups hired by this company, Yaki's group had to cover their own travel expenses. By then, the Meiji company had already suspended its activities since 1909.

During the rubber boom (1885-1915) foreign labor was hired. Between 1905 and 1909, the Japanese immigration companies Morioka and later the Meiji signed contracts with the Inca Rubber Company to bring Japanese immigrants to the Tambopata area. When the price of Peruvian rubber dropped drastically in the face of foreign competition, the Inca Rubber Company unexpectedly decided not to hire any more Japanese immigrants, even those who had recently arrived in Peru. Meiji had to informally relocate them to coastal farms, where they received all kinds of abuse and wages below the agreed amount.

Empathy for fugitives

Dissatisfied with the mistreatment and low wages, many Japanese immigrants fled the haciendas to Lima. They crossed the desert on foot, even risking their lives: some were shot dead, others died or were robbed along the way, or women were raped.

When they arrived in Lurín, Yaki welcomed them into his home. Generally, they were groups of two to eight people. Yaki gave them clothing and food, admitted the sick to the hospital and, for the strongest, gave them work. He was responsible for burying the deceased and placing flowers on them. Yaki saved the lives of many immigrants.

Okinawan Youth Association

Faced with this need, Yaki decides to form an association. Together with thirty other people, Yaki founded the Okinawan Youth Association (Okinawa Seinen Kai) on July 30, 1909, which would later be called Peru Okinawa Kenjinkai (current Okinawan Association of Peru). Its creation was intended to help immigrants in need. For Yaki, what was urgent was to acquire accommodation for the fugitive immigrants, assist them in case they required hospitalization and help them with learning Spanish. Together with Junsuke Kishimoto, treasurer of the association, Yaki traveled to areas with the largest Japanese population in search of donations. He managed to raise enough money and they rented the attic of a house, where Yaki moved seven patients he was staying in his house.

Over time, massive escapes increased and with them, the fugitives who arrived at Yaki's house, who could no longer supply himself. The situation of the deceased also worried Yaki. When he was in Cañete, he saw that the bodies were not buried early to save time. It was the time when deaths occurred almost daily and the bodies were buried together, allowing them to accumulate. This way the Japanese would not lose days of work to celebrate individual funerals and would avoid complaints from their employers. Those who were already buried were condemned to oblivion, with improvised tombstones and at the mercy of the cattle that roamed freely. Yaki gathered and buried all the scattered remains in a common grave, ordering an obelisk to be built in his memory.

With the concern of creating an organization that represented all Japanese in Peru, the Japanese Fraternal Association (Nihonjin Dooshikai) was founded in 1910 and which would later become the Central Japanese Society (1917) and the current Peruvian Japanese Association (1984). . Sentei Yaki was elected president of the Central Japanese Society in 1928 and the first president in the history of the Okinawan Association of Peru, where he was re-elected three times.

Promoted the use of tanomoshi

The use of tanomoshi was born in the Okinawan Fraternal Association, at the initiative of Sentei Yaki. With this system based on mutual trust, many Japanese immigrants were able to open their own businesses. Because they did not master the Spanish language, the Japanese viewed the Peruvian financial system with suspicion (and vice versa). In the beginning, tanomoshi were mainly used to help the sick, bury the dead and solve emergencies in general. For women, it was a means of savings for housewives and a way of socializing; and for merchants, a way to create capital to start a business.

The dreaded blacklist

Sentei Yaki was a prominent member of the Japanese community and for the Peruvian authorities, a suspicious Japanese. On January 12, 1943, Sentei Yaki was forcibly taken from his own home to the Crystal City concentration camp in the United States. Along with other Japanese, Sentei Yaki appeared on the feared blacklist of Japanese who would be used for the exchange of American prisoners. After six months of detention, Yaki was able to join his wife and children Germán, Nobuko and Ochi in Crystal City, where they were allowed to live as a family. After the war, Yaki was able to return to Peru thanks to his Peruvian nationality.

Memories and recognitions

Sentei Yaki's life was recorded in his autobiography Gojyunen zengo no omoide , which he published in 1963 and where he recounts the memories of his 50 years lived in Peru. Yaki was decorated in 1966 as an outstanding Japanese of Peru in the name of the Emperor of Japan, being one of the first four Japanese to receive such a distinction.

Likewise, in 1974, during the central ceremony commemorating the 75th anniversary of Japanese immigration to Peru, Yaki was honored as a survivor of the fourth group of immigrants that arrived in Peru in 1907. Two years later, on June 19, 1976, He passed away, leaving in our memory the example of a leader at the service of his neighbor.

SOURCES:

Museum of Japanese Immigration to Peru “Carlos Chiyoteru Hiraoka”. MATSUDA, Samuel. Walking for 75 years on the roads of Peru . FUKUMOTO, Mary. Towards a new sun . TIGNER, James Lawrence. The Okinawans in Latin America .

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 114, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2018 Texto y fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa