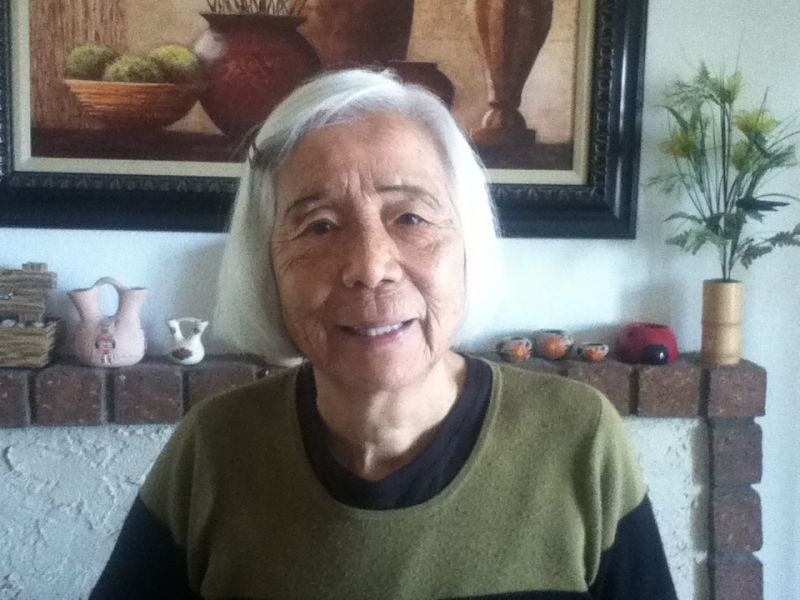

Author’s note: Kiyoko Wells and I met each other by chance, as a result of a series of rolling blackouts that affected Southern California, during a hot summer day, a few years ago. She lives several houses away from my parents’ home, and after a random encounter and conversation with one of my sisters, my family has cultivated a profound friendship with Kiyoko, so much so that we consider her part of our family.

* * * * *

In August of 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.1 World War II had been going on for approximately five years, and the decision to test these experimental weapons of mass destruction was made under the Truman administration.2

Kiyoko Wells was a child when the bombings took place. She was born on November 8, 1932 in Sasebo, Kyushu, Japan. Sasebo was a rural fishing village, and in 1886, was chosen as the ideal location for an American naval base. During our conversation, Kiyoko spoke about her childhood as being one of many perils and dismays. After the bombing and the end of the war, a long occupation ensued, which particularly affected Kiyoko’s village. This paper elaborates on Kiyoko’s migration story and contextualizes her journey with historical events and sociological occurrences that were taking place at the time.

Death, war, and occupation; this is what Kiyoko mainly remembers of her childhood in Japan. She was just seven years old when World War II began and when her mother passed away.

She told me, “Everybody got hurt after [the] war came… that time [was] very, very bad… [many] lost [their] home, job, family, and economy is bad so, everybody is hurting.” She adds that, “Even the school was burned and no such thing as a 100% education because most of the time you [have to]… hide [in a] bomb shelter.” She said that when the bomb sirens wailed, everyone went different ways, because it was just too dangerous to be in the house and the likelihood of survival was heightened if they each went in random directions.

Kiyoko was thirteen years old when the United States bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I asked Kiyoko what life was like after the bombings, and she explained to me that, life in Japan was terrible, even more so during the occupation.

She told me that there was a lot of fear. “It [was] just too much at once, but you got to survive, so everybody doing the same way, [surviving], but economy was very, very bad and… you have to live, you are young, everybody just [make] the best out of it and [take it] day by day. That’s the way my teenage years went.”

Kiyoko lost most all of her friends as a result of the bombing, or due to tuberculosis, malnutrition, and illness caused by breathing toxic air. It goes without saying that those who did not die instantly were greatly affected by the aftermath of the bombings and occupation.

Yamada and Izumi expand on the effects that the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had on the psychological well-being of those affected, and found that, “The prevalence of anxiety symptoms and somatization symptoms was elevated in atomic bomb survivors even 17–20 years after the bombings had occurred, indicating the long-term nature of the psychiatric effects of the experience.”3

She credits her survival and that of her family, to her father’s small vegetable garden, which allowed them to barter food and other items with neighbors, and the river that divided them from Nagasaki, as it served as a type of natural diffuser between Sasebo and ground zero.

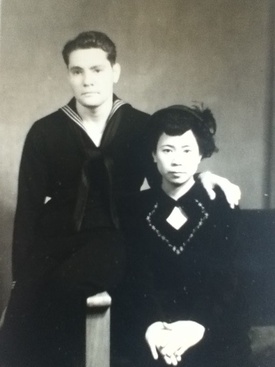

She met her late husband, Richard, a recently discharged Navy Seal, when she was twenty years old, and shortly after, moved to the United States. She was quick to accept his marriage offer, as she was in love with him, but also because she saw this as an opportunity to escape all of the pain and suffering she had endured. Given that she was not twenty-one, she needed either her father or her eldest brother to sign consent, neither of whom choose to do so right away.

Unlike the picture brides that Takaki speaks about, Kiyoko’s family did not encourage her to marry an American, largely because of the tension between the two countries.4 With tears in her eyes, Kiyoko told me that her brother and father disowned her. Her brother told her she was marrying the enemy, and her father told her that he would sign, but that it would mean that she would never be welcomed in the family again. Six months later, her father signed the marriage documents, and went to the train station to send her and her husband away, with tears in his eyes.

In September 1953, Richard and Kiyoko, pregnant with their first child, made the journey to the United States on a two-week trip on a Navy ship. Their initial plan was to put down roots in Brooklyn, New York, Richard’s hometown, but given the multiple California Alien Land Laws of 1913, 1920, and 1923, and its lasting anti-Japanese effects, Kiyoko and her husband were limited in the states that they could settle in, and decided to settle in California.5

She explained to me that in Japan, “society [was in a stressful] situation, but people… accepted each other and tried to help support each other,” which has not always been her experience while living in the United States; just a decade prior to Kiyoko’s arrival, the U.S. had openly imprisoned persons of Japanese descent in internment camps.6 (National Archives).

Kiyoko and her husband lived with his parents and siblings for all of one month; it was a long and terrible month, during which she endured racism and harassment by part of his family, but most especially from her mother-in-law, all while pregnant, and trying to adjust to a completely different life, away from home, away from her family, away from her culture.

She shared with me one particular moment that she will never forget. Her husband was finalizing the documentation to rent a house in San Diego. Everything was going well, the renter had approved him, that is, up until Kiyoko walked into the real estate office; the woman saw her and simply said no, “you can’t rent my house because your wife is oriental;” similar to the racially restrictive covenants that Takaki referenced.7 Kiyoko and her husband were furious, saddened and deeply hurt. She remembers how upset her husband was and how baffled he seemed.

The following year, in 1954, they bought a home in Ontario, California. During the first four years of her being in the U.S., she felt extremely isolated, having to constantly deal with hurtful stares, and expressed to me that she felt as though she were choking, given that she could not fully express her frustrations to anyone, including her own husband; he spoke a bit of Japanese, and she spoke very little English. She felt isolated, and, as Portes and Rumbaut explain, Kiyoko, like many Japanese immigrants, turned to Christianity as a support network to help her get through the difficult times she was living.8 Additionally, she did not experience any of the labor force tensions that Takaki references because she did not work; her husband held a high-ranking position in an important company and earned enough money to be the only breadwinner.9

Kiyoko told me that she believes that most people do not consider her to be American. She elaborates in saying that, “I look different. I talk different. I believe differently.”

She told me that she has two cultures: American and Japanese, and that she has learned to take the best parts of each. There are parts of her Japanese culture that she has not and will not let go: her choice in food and her belief system. Simultaneously, she told me how grateful she is to live in a country that values freedom of speech, upholds liberties, and has laws that, for the most part, protect its people.

The interview concluded with her giving advice to newly arrived immigrants, saying that they must give themselves time to experience and heal, and added that they must take care of themselves, maintain good judgment, share with others, and lastly, to have a beautiful life.

Note:

1. “Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” History: A&E Networks Digital. Retrieved on April 7, 2014.

2. “51g. The Decision to Drop the Bomb.” U.S. History: Pre-Columbian to the New Millennium. Retrieved on April 7, 2014.

3. Yamada, Michiko and Shizue Izumi. “Psychiatric Sequelae in Atomic Bomb Survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki Two Decades After the Explosions.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (2002) 37(9):409-15.

4. Takaki, Ronald. 1993. A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America. (Boston, Toronto, and London: Little, Brown and Company, 1993), 247.

5. Portes, Alejandro and Rubén G. Rumbaut. Immigrant America: A Portrait. (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 2006), 40.

6. “Teaching With Documents: Documents and Photographs Related to Japanese Relocation During World War II.” The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved on April 7, 2014.

7. Takaki, A Different Mirror, 274.

8. Portes and Rumbaut, Immigrant, 326

9. Takaki, A Different Mirror, 251

*This article was originally published on Immigrant Voices by the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation.

© 2018 Kristi P. / Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation