Eight Japanese men gathered at the Tamagawa Tei restaurant on First Street in downtown Yakima to recite their poems and judge the others. On this fall day in 1912, members of the Yakima Ameikai — Yakima Croaking Society — met for the first time.

All seasonal farm workers, they wanted something more than just gambling, smoking and drinking sake during their time away from work in the fields. They wanted companionship and culture. They wanted to express their feelings in a way that each could understand and appreciate.

They chose senryu, an unrhymed Japanese verse consisting of three lines of five, seven and five syllables. And in meeting that forgotten day in Yakima, they formed the first reading circle for senryu poets in the U.S.

With origins in the 18th century, senryu — also called human haiku — is usually written in the present tense and highlights some aspect of human nature or emotions, often humorous but sometimes poignant. For the Japanese immigrants who began arriving in the Yakima Valley in the 1890s and those who followed, senryu captured their hopes, wishes and dreams.

“The poets were ordinary people, ranging from immigrant leaders to seasonal workers, male and female, young and old. Collectively, they tell of the life and sentiments of the immigrants,” Teruko Kumei, a professor in the English Department of Shirayuri College in Tokyo, wrote in a 2005 article in The Japanese Journal of American Studies.

“The poems express how Japanese immigrants felt about homesickness, sense of non-belonging, labor, discrimination, marriage, community, (their) children, cultural collisions, Japanese national pride, U.S.-Japan relations, and their new land.”

Members of the Yakima Ameikai met every Saturday for two years until their leading member, Shinjiro “Kaho” Honda, left for Japan. He returned to America in 1929 and helped found the Hokubei Senryu Gosenkai (Senryu Society of North America) in Seattle, according to Kumei. Many members of the Yakima group joined and also restarted their own senryu circle.

More senryu circles formed in Seattle, Longview, Snoqualmie Falls and Portland, communicating and competing with each other for bragging rights and enormous silver trophies.

Gail Nomura, a retired associate professor of American ethnic studies at the University of Washington, like Kumei is an expert on Japanese immigrant poetry. She and Kumei translated poems used in the Yakima Valley Museum’s ongoing exhibition, “Land of Joy and Sorrow: Japanese Pioneers of the Yakima Valley.”

Senryu offers a way into the world of the Pacific Northwest’s Japanese American community before, during and after their forced imprisonment during World War II changed that world forever.

“These people were recording not only their own history through their publication ... they were also writing of everyday life in their poems,” Nomura said.

To the west I look,

twenty years, day after day.

(My) tears wet the sky.

— Kido (1934)

Kumei decided to study senryu poems made in the U.S. about 20 years ago when some fellow professors started a research project. Having searched multiple issues of many Japanese language newspapers across the country, she has amassed a collection of more than 15,000 poems written by Japanese immigrants from the late 1920s to the end of World War II.

“I knew this would be an interesting topic. I knew there are a great many senryu and haiku poems in the Japanese language newspapers,” she said in an email.

She found Yakima’s senryu circle amid that research.

“It is true that you can find senryu poems in the Japanese language papers in the 1900s, but as for the senryu reading circle, I could not find any earlier than that of Yakima,” she wrote in an email.

“The Yakima group is important in the sense of human connection.”

Her research revealed what had been forgotten, rediscovered in the final month before “Land of Joy and Sorrow: Japanese Pioneers of the Yakima Valley” opened at the Yakima Valley Museum in Yakima in October 2010.

Two years in the making, the exhibition traces the story of the Japanese families who settled in the Yakima Valley, the forced relocation of 1,017 valley residents of Japanese heritage to Heart Mountain, Wyo., in 1942, and the reemergence of the valley’s Japanese American community after World War II.

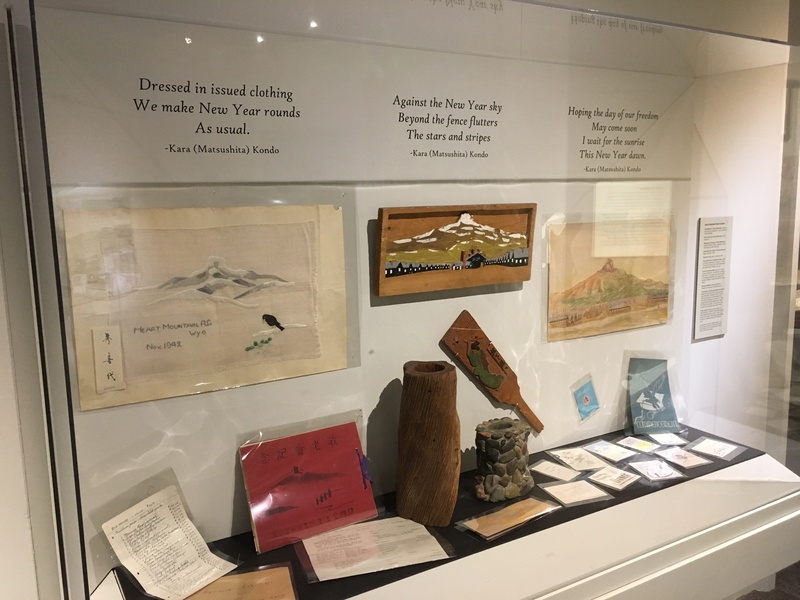

Visitors see examples of senryu, along with haiku and tanka — another form of Japanese immigrant poetry — throughout the exhibition.

“(Nomura) brought Masako Notoji, professor at the University of Tokyo, to the museum while we were starting to put the exhibit together. Professor Notoji gave us the amazing history of the senryu poetry circle weeks before the exhibit was to open,” said Mike Siebol, the museum’s curator of collections.

Senryu debuted as a new poetic form later in Japan’s Edo period (1602-1869). A poetry master named Karai invented a style of verse that was similar to haiku but was inspired by daily life instead of the natural world. Senryu also differed in that it’s witty and even sarcastic, and occasionally racy.

The new form of poetry got its name from its creator’s pen name — Senryu.

A key component in the enjoyment of senryu is instant recognition of the scene described through the poet’s precise observation.

LLyn De Danaan, an anthropologist and author, has studied and written about the history of Japanese Americans. A speaker for Humanities Washington and professor emerita at The Evergreen State College, she has documented the work of several senryu poets.

“(Consider) what it takes to create an image that’s so condensed ... and that it carries the weight of an emotion or an image,” said de Danaan, who also knows the poetry’s challenges from writing her own senryu.

It’s also a valuable way to keep one’s culture and language alive, she noted.

Senryu is a democratic style of verse in that all could participate. The Longview senryu circle included women, noted de Danaan, who has documented the work of two modern female senryu poets, Miyoko Sato and Yukiko Abo. Their words provide a unique perspective on the everyday world of Japanese American women living and working on Oyster Bay.

“I know some of Mrs. Abo’s (senryu poems) are about an ironing board or seeing the white of her husband’s lantern out on the bay,” De Danaan said. “It’s a real woman’s point of view.”

Next morning,

all sobered up. Damn.

Sake brewed brawls.

— Shigetaka “Kentsuku” Kurokawa (1912)

The precise observation and instant recognition required by senryu show why Kurokawa’s poem blaming the sake took top honors at the Yakima senryu circle’s first gathering.

“This senryu poem evokes a scene: Immigrant workers come out of a labor camp on a Saturday night to a Japanese sawdust parlor; friends meet and have a nice chat over drink after drink; drunk, they have a brawl over a trifle; the next morning, they meet, feeling ashamed, and apologize; ‘Sorry, it was because of sake. Sake drove me insane,’” Kumei wrote in “Crossing the Ocean, Dreaming of America, Dreaming of Japan: Transpacific Transformation of Japanese Immigrants in Senryu Poems; 1929-1941,” published in The Japanese Journal of American Studies in 2005.

In those days, Kumei wrote, the immigrants were without family. Sake was their most potent diversion.

“Immigrants who came to the senryu gathering understood exactly what the poem meant, and they ranked it as the best,” she wrote.

Members of the senryu poetry circles in Washington and Oregon met to write and improve their poems through competition and collaboration. They not only socialized with but also learned from their fellow poets at the weekly meetings, presenting poems they had likely started composing while at work.

“They would come back (from working) and write them down and would continue to revise them,” Nomura said.

Senryu poems also offered children insight into the challenging lives their immigrant parents faced, she noted.

“If you talk with many of the families ... the older Nisei, the second generation, they would often tell me, ‘I discovered that our father was a pretty good poet,’” she said. “They didn’t realize what their parents were really doing; they were young children.”

The senryu tradition in the Yakima Valley continued for decades after the poetry circle began meeting. Members entered their poems in competitions at one of the leading senryu reading societies in Tokyo, where they earned high praise. A 1928 publication, “History of the Japanese People in the Yakima Valley,” noted with pride that local immigrant senryu poets were recognized as equal or superior to leading senryu poets in Japan.

And the valley’s poets continued to see their words appear in the North American Times and other Japanese newspapers in the United States, with some featured in a collection of senryu printed in 1935 — the first collection of that poetry published in America.

Dressed in issued clothing

We make New Year rounds

As usual.

— Kara (Matsushita) Kondo

(Senryu written in a Heart Mountain poetry class)

When Kumei began her senryu research, she found and interviewed some of the original members of Los Angeles senryu groups who were incarcerated during World War II. As it did for Japanese immigrants, senryu offered community and creativity in challenging times.

In his 2010 article, “The Senryu Tradition in America,” C.E. Rosenow noted how senryu poet George M. Oye stressed the importance of writing senryu and attending senryu gatherings during his World War II imprisonment in “America’s concentration camps.”

“Because of our desolate feelings of helplessness in the unpleasant surroundings, I looked forward to the weekly gatherings of fellow poets under the leadership of Shimizu Kicho. It was like an oasis in the desert,” Rosenow quoted Oye saying in his 1981 book of original senryu, “Nameless to Nameless.”

Honda, the leading member of the Yakima senryu circle, also was forced from his home. He had returned to Seattle from Japan in 1929, and years later moved back to the Yakima Valley with his only child, Teresa. Honda’s wife had died in 1928.

Born in Japan in 1877, Honda was 65 years old when he and Teresa, who was 19, went to Heart Mountain from the Portland Assembly Center on Sept. 1, 1942. He died there on Sept. 3, and funeral services took place at Block 15-25 on Sept. 5. Teresa had no children.

A monument on private property in Seattle honors his contribution to the senryu tradition in America.

The East Asia Library, part of the University of Washington library system, provides research help and access to Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Tibetan resources.

“(The University of Washington) has a nice collection of senryu materials,” said Kumei, who traveled to Seattle in 2010 for her research at the library on “Immigrant Senryu Clubs and Japan, 1930s-1950s.”

Azusa Tanaka, head of Japanese collections at the East Asia Library, noted that the nearly 150 publications on senryu there and at the university’s Suzzallo and Allen Libraries — articles, books and more — span 1910 to 2011.

De Danaan spoke at a haiku conference a few years ago and was surprised that organizers were unaware of the rich senryu tradition in the Pacific Northwest and how important the poetry was in the Japanese immigrant experience, and how their words still resonate today.

“This was a very active part of their lives,” she said.

*This article was originally published by the Yakima Herald-Republic on February 18, 2017.

© 2017 Tammy Ayer