Chris Shinya Tomine’s recognition as an artist started as a simple request, being asked to create posters publicizing annual events held at the Alameda Buddhist Church. The posters did their job and attracted participants to the occasions, but afterward became sought-after collectible artworks.

“Back in 2000 the Buddhist Temple of Alameda asked me if I would do posters for their functions,” Tomine said. “They have two big events, an annual bazaar and the Obon. I said I would. I’ve been doing the posters for them ever since.”

The Buddhist Temple of Alameda located at 2325 Pacific Ave. holds a bazaar every year in June, a major fund-raising event for the church. In addition the temple is a central participant of the annual community Obon Festival held in July. Obon is a celebration of one’s departed ancestors and involves Bon Odori (folk) dancing, food, exhibits, and Japanese cultural performances.

A large part of the success of the events and a good turn-out depends on the posters displayed around the community of Alameda, a city of about 99,000 located on the Peninsula just south of Oakland and in other Bay Area cities.

Every year Tomine has to come up with new posters featuring new themes for both the bazaar and the Obon, art intended to inform the public as well as entertain.

“I usually try to work in a little humor in my artwork,” Tomine said.

The portrayals achieved a local renown to the point that a major showing of his artworks was held last year at the Alameda Buddhist Temple during observances to celebrate the church’s 100th anniversary.

“About 30 of the artworks were put on display and many were sold,” Tomine said. “All the money raised from the sales went to the church.”

Tomine can trace his ancestors on his father’s side to the city of Itako in Ibaraki Prefecture (State) on the coast west of Tokyo. His mother’s relatives came from Kyushu Island at Japan’s southern tip.

Both his father Susumu Tomine and his mother Tomoe were imprisoned at the Tule Lake Segregation Center for Japanese and Japanese Americans, accused of disloyalty by the U.S. Government in 1942 during World War II. Tule Lake located in a remote part of Northeastern California was a prison for those judged to be the most recalcitrant of inmates.

“My parents rarely talked about it when I was growing up, but I think they were sent to Tule Lake because my father answered “No No” to the (loyalty) questionnaire,” Tomine said.

Inmates including the elderly were asked to answer a loyalty test —–including questions 27 and 28—in which prisoners had to renounce loyalty to the Emperor of Japan even though as U.S. citizens they usually had no such loyalty to the Japanese Emperor to begin with.

Those who answered yes were often sent to slightly less high-security prisons such as that at Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

“After the war my dad worked as a gardener and my mom was a hair stylist,” Tomine said. “My brother and I spent many years, Saturdays and summers, helping my dad.”

Tomine attended Alameda High School and then UC Berkley earning a bachelor’s degree in engineering physics. He achieved a Master’s Degree in physics from Oregon State University and a PHD in mechanical engineering.

“I finished my studies in 1972 and moved to Sacramento,” he said. “I got a job as a professor at California State University, Sacramento. I was a university Associate Vice President and Civil Engineering Department chairman. For a time I was also interim chair for the Department of Asian American Studies.”

Tomine served in the professorship position 30 years teaching students basic engineering skills plus instruction on environmental issues, the technological aspects of air pollution, its monitoring and control.

Today retired, Tomine said he had been interested in art since childhood.

“As an adult it was nothing professional or dedicated,” he said. “I was what in Japanese we call a ‘tokidoki’ (occasional) artist.”

His wife Jane Naito is a well-known teacher of the art of ikebana (Japanese floral arranging). She provides valuable advice on each poster that Tomine produces.

“She critiques my work,” he said. “She has a great artist’s eye.”

To date Tomine has produced approximately 34 posters for the Alameda Buddhist Temple.

To get ideas he said he looks at artwork on calendars, Japanese wood block prints, books, and other sources.

“About every April and May my feet are to the fire because of a deadline and I have to come up with new posters,” he said. “I do them on my computer with Adobe Illustrator (software). Using my computer mouse I do an outline and then fill it in with colors.”

One poster depicts a Japanese samurai (warrior) at a church function eating udon (broad noodle). Another is a samurai holding aloft a bingo card and yelling “bingo!” The samurai has been a popular theme over the years and another poster portrays an iconic warrior figure at a church event eating a hot dog.

Yet another poster shows a woman dressed in kimono singing at the Obon Festival, while another poster shows a kimono-clad woman oblivious to the Obon dancers making a call on her cellular phone. The humor injected in such renderings often includes the ironic and the slightly implausible.

“I don’t produce posters in a solid block of work time,” Tomine said. “I work on one for say eight hours and then knock off and let it rest. You can sometimes come up with better ideas in the interim. I work in fits and starts.” A project can take two weeks or longer to complete.

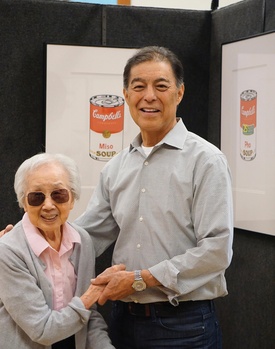

One of his more unusual artworks does a take-off on the famous Andy Warhol print of a Campbell’s Soup can, only in this case changing it to an Asian Miso Soup label can.

“That was a parody of Warhol’s parody of a soup can,” Tomine said.

When not working on his art Tomine said he likes to play a little golf and also plays and sings in a local seven-member guitar ensemble band.

People avidly seek to gain possession of the posters once an Alameda Buddhist Temple function is over and the posters come down off walls. Up to 100 or more are reproduced and posted in stores, restaurants, and other businesses in the area.

“One was put up at a real estate office and people wanted to know if they could have it after the event was over,” Tomine said.

He said it’s a good feeling to have his artwork appreciated.

“People have told me how much they enjoy seeing it and that makes me happy.”

Examples of the art can be seen by going to the Buddhist Temple of Alameda website.

*This article was originally published on Nikkei West on March 19, 2018.

© 2018 John Sammon