The historical narrative surrounding the wartime confinement of ethnic Japanese in the United States grows ever more complex. In the last years, historians and activists working with community organizations (in some cases with government funding) have made significant discoveries. The Honouliuli Internment camp in the then-Territory of Hawaii, whose site remained long hidden from view, was located and explored, and was ultimately named a National Monument. The Tuna Canyon Detention Station near Los Angeles, where Issei men arrested by the FBI after Pearl Harbor were held, was rediscovered and its history documented. The War Relocation’s illicit “isolation center” at the former Indian boarding school at Leupp has been revealed in such works as filmmaker Claudia Katayanagi’s documentary A Bitter Legacy. Scholar Anna Pegler-Gordon’s new research explores the wartime internment of Japanese aliens at Ellis Island in New York.

Yet amid all this new activity, the existence of one confinement site on U.S. territory is still generally unacknowledged: The Panama Canal Zone, where Japanese aliens (along with Germans and Italians) were incarcerated throughout the war years.

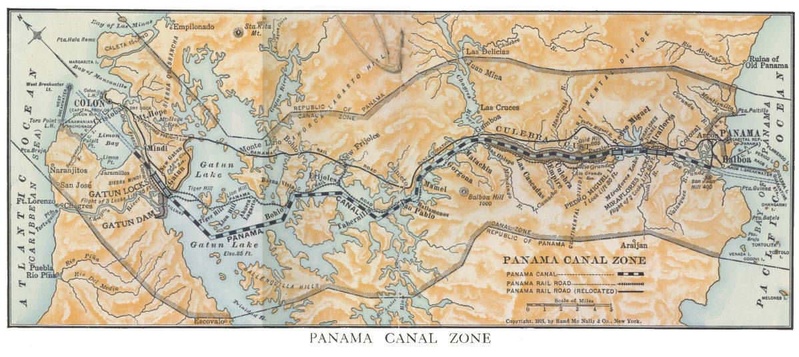

The Panama Canal, ceded by Panama to the United States via the Hay-Bunau Varilla Treaty of 1903 and constructed between 1904 and 1914, was one of the major accomplishments of the early Twentieth Century in terms of technology and defense. Yet by its creation, this “path between the seas” about 10 miles wide and 50 miles long gave rise to repeated struggles and conflicts between Americans and Panamanians, and at a larger level between Washington and Latin American countries. These struggles, shaped by race, culture, politics, revolved around the question of sovereignty over the Canal Zone, the strip of territory surrounding the canal, which the Americans controlled under the 1903 treaty, but which cut the Republic of Panama in two. The bad feeling this separation created among Panamanians led to disturbances in the Canal Zone and in Panama. During this early time of possession, the United States multiplied its military interventions inside Panama in order to maintain order in the country, in a total abuse of Panamanian sovereignty.

Following requests by the Panamanians in 1921 and 1923, the United States agreed in 1926 to renegotiate the 1903 treaty. Nonetheless, this renegotiation failed to resolve Panamanian grievances concerning repeated violations of Panamanian sovereignty by Washington. In the 1930s, in connection with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor Policy” towards Latin America, a new agreement was reached between the two countries, which postponed the question of sovereignty to the post-war period. (During the 1950s and 1960s, Panama would renew and extend its sovereignty claims amid rioting in the Canal Zone, until the two nations signed a new treaty in 1977 providing for the handover of the canal).

Nonetheless, as a result of the Roosevelt Administration’s diplomacy, the Panamanian Government collaborated closely with the U.S. War Department during the World War II period. During these years, the protection of the Canal Zone was of paramount interest to Washington, since the Panama Canal was central, not just to the defense of the United States interests in the region, but to the security of all the nations in the Western Hemisphere that were engaged in the war. The Canal was the only secure maritime link between the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans. Moreover, the operations of German submarines in the Caribbean boldly dramatized the potential vulnerability of the Canal and the need for reinforcement of the Zone.

In negotiations with the United States, Panama’s government agreed to the potential formation of a new national army to support Canal defense and promised to ensure coordination and cooperation between the Panama Canal Police and the Panamanian Police. The area of most visible collaboration was in the wartime internment of Japanese aliens.

While the historical literature is scanty (notably, there is no entry on Panama in The Encyclopedia of Japanese Descendants in the Americas) what seems clear is that throughout the prewar period there were Nikkei in the isthmus—by 1941 the community numbered an estimated 400. The Chicago Tribune stated in 1940 that Japanese made up a visible part of Colón’s population. Some individuals resided inside the Canal Zone. For example, California-born Ralph Toshiki Kato was listed as living there in 1935.

Thus, as relations between the United States and Japan grew tense, authorities put pressure on Japanese citizens, viewed as a potential security threat, to depart. When the Japanese freighter Sagami Maru passed through the Panama Canal in fall 1940, the ship’s crew reported that some 20 U.S. Army officers boarded the ship for inspection. In July 1941, pretexting the need for repairs, American authorities closed the canal to Japanese ships. In fall 1941 the government of Panama forbade Japanese citizens from doing business within its territory. In October 1941, according to historian C. Harvey Gardiner, U.S. Ambassador to Panama Edwin Wilson began discussions with Panamanian Foreign Minister Octavio Fabrega. The Panamanians agreed that following any action by the United States to intern Japanese residents, Panama would arrest Japanese on Panamanian territory and intern them on Taboga Island. All expenses and costs of internment and guarding would be paid by the United States Government, which would hold Panama harmless against any claims that might arise as a result.

In November 1941, Attorney General Francis Biddle hinted that the government was planning mass confinement in Panama. Biddle announced that Justice Department experts had decided against wholesale arrests—it would be unwise to treat all Japanese living in the United States as enemies—but he added that the Canal Zone and Hawaii were different, and “temporary” mass arrests there were likely.

The various plans were translated swiftly into action following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941. According to Wilson’s later testimony, within 20 minutes of the announcement of the Pearl Harbor attack, Panamanian authorities began rounding up Japanese and German aliens throughout the Republic. Once rounded up, the Japanese were summarily turned over to US authorities, and transported into the Canal Zone for internment in “concentration camps.” The New York Times reported that 57 Japanese in Colón were delivered to US authorities, and 114 more were expected from Panama City. The Times added that the Japanese were being held in a quarantine station in Balboa, but that tent cities were being constructed to house the influx.

Meanwhile, Canal Zone police, working in coordination with the Panamanians, took Japanese there into custody. (In her article for Discover Nikkei, “Yoshitaro Amano, Canal Zone Resident and Prisoner #203,” Esther Newman discusses in detail the experience of one of these Japanese, her grandfather Yoshitaro Amano, based in part on his 1943 Japanese-language memoir, Waga Toraware No Ki.) Newsday stated that some 300 Japanese in the Canal Zone were being interned indefinitely as enemy aliens.

By January 1942, according to newspaperman Nat A. Barrows of the Chicago Daily News, 185 Japanese were held as civilian internees in a camp “somewhere in the Canal Zone,” within a larger camp with separate facilities for Germans and Italians.

Outside the camp, in a former private club, 34 women and 47 children were confined. 400 other enemy aliens had been arrested, he claimed, then released after hearings, while a Nisei from the Canal Zone had been transported to California. Barrows asserted that the Americans intended to hold the internees until the Republic of Panama built its own camp, and then take over all internees except for the 15 who were arrested inside the Canal Zone. Barrows lauded the treatment of the Japanese:

“Most of them never have had such good food and such good quarters before. In the daytime they lounge in the shade or do light work about the camp. In the evening they indulge in wrestling in an earthen ring or just sit expressionless studying their guards.”

However, this idyllic picture is contradicted by Amano, who described the Japanese aliens as housed in makeshift tents in a concentration camp. Amano spoke of the demanding physical labor the Japanese, many middle-aged, were forced to perform. Amano’s account is seconded by the claims of the Japanese government. When in spring 1944 Washington lodged a formal protest against Japan for its treatment of American captives, Tokyo responded in a letter to the Swiss legation denying ill-treatment of prisoners, and complaining of the treatment of Japanese nationals in U.S. custody.

“The Japanese who were handed over to the United States army by the Authorities of Panama at the outbreak of the war were subjected to cruel treatment, being obliged to perform the work of transporting square timber, sharpening and repairing saws, digging holes in the ground for water closets, mixing gravel with cement and so forth. The internment Authorities let the Japanese dig a hole and then fill it again immediately, or let them load a truck with mud with their bare hands using no tools. Neither drinking water nor any rest was allowed. The Japanese who were exhausted and worn were beaten or kicked and all this lasted over a month.”

The Japanese note referred to the lack of medical care.

“One Ouchi was gravely ill when he was handed over to the American Authorities in Panama, but the Authorities gave him neither medical treatment, nor liquid nourishment which was all he could take. His wife requested that he be taken into Panama hospital but the request was not heeded, and he was sent on to Fort Sill in April 1942 together with other Japanese internees. As no nurse was provided at the new camp, his fellow internees looked after him, but no medical treatment having been given, he finally died on May 1st.”

In April 1942, the interned Japanese were sent to internment camps on the mainland. The Associated Press ran a photo of Japanese enemy aliens being “evacuated” from the Canal Zone in a railroad car with blackened windows. The caption mentioned (based on undisclosed information) that one of the men was a “Japanese naval officer,” while two others were “Japanese Army reservists.” The camps in the Canal Zone were subsequently mobilized by the U.S. government to hold Japanese Peruvians who had been summarily taken into custody and shipped north to the Canal Zone. There they spent several days or months in confinement, forced to work without pay to clear jungle and construct living quarters amid the heat and the pouring rains. As Gardiner later reported:

“Denied communication with their families, unaccustomed to hard labor, resenting the unsavory food and their inadequate shelter under intolerable weather conditions, the men understandably put forth no special effort. In return guards occasionally kicked, beat, or nicked with their bayonets some passive worker.”

Grace Shimizu, daughter of a Japanese Peruvian detained in the Canal Zone camp, later shared the testimony of another internee about being put to work clearing the jungle around the camp.

“One humid day the internees, many of whom were elderly, were told to dig a pit. He thought he was digging his own grave. When they were told to fill the pit with buckets of human waste from the guards' latrines, then the older men were so tired that they could not run fast enough to please the guards, they were poked and shoved by guards with bayonets.”1

Why does this matter? First, because the fluid nature of sovereignty and control on US territory raises important questions of human rights. The United States confined people in the Canal Zone without due process, even though they were supposed to be covered by the Constitution, while the Republic of Panama colluded with the United States to transfer citizens and legal residents for confinement. As we have seen in the matter of current-day confinement of “enemy combatants” at Guantanamo, constitutional rights of detainees are threatened where governments can create gray areas. Also, the confinement in Panama set a precedent. In her article, “Forsaken and Forgotten: The U.S. Internment of Japanese Peruvians During World War II” Lisa C. Miyake proposes that the imprisonment of Japanese Panamanians in 1941 became a model for the internment of all suspicious Latin Americans.

Note:

1. Testimony of Grace Shimizu, in “Treatment of Latin Americans of Japanese Descent, European Americans, and Jewish Refugees During World War II,” Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, Refugees, Border Security, and International Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, First Session, March 19, 2009

© 2018 Greg Robinson, Maxime Minne