The former Temixco Hacienda is home to one of Mexico’s best-known and popular water parks. The vestiges of the hacienda that still remain—including the parish church and extensive gardens—lend a particular beauty to the place. Temixco (a Náhuatl word that roughly translates to “where the rock of feline is”) is near the city of Cuernavaca and has an average temperature of 20º C (68º F).

But hidden deep in this heavenly place where the flowers always bloom is a little-known story of great importance to the history of Mexico and Japanese immigrants.

When war broke out between the United States and Japan in December 1941, the U.S. government asked that all Japanese immigrants and their descendants be moved away from the border and concentrated in Mexico City and Guadalajara so they could be closely monitored. In January 1942, immigrants living in the states of Baja California, Sonora, and Sinaloa were the first to receive the order to move.

The Japanese who were already living in Guadalajara and Mexico City created the Kyoei-kai (Mutual Aid Committee) to welcome and support their compatriots, who began arriving from different parts of the Republic in January 1942. In addition, the Committee was authorized by the Mexican government to serve as a representative body in relations with the government and carry out all procedures required during that time of war.

In Mexico City, the Committee welcomed the families and notified the Directorate for Political and Social Investigation (known as DIPS), part of the Interior Ministry, of their arrival and residential addresses. The displaced families were temporarily housed at the Committee’s own offices, located on Sor Juan Inés de la Cruz street close to the city center.

One of the families that moved to Mexico City in June 1942 included a little girl by the name of Rosita Urano. Rosita and her two siblings, Alejandrina and Filemón, were from Veracruz state. Their father, Yashiro Urano, was Japanese, and their mother, María Hernández, was Mexican.

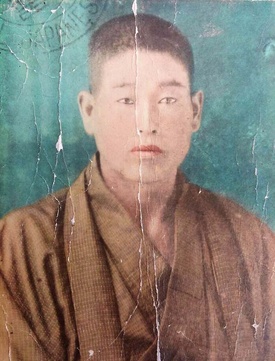

Yashiro Urano, originally from Kumamoto prefecture, had come to Mexico in 1927, pursuing a job offer at a grocery store belonging to a fellow Japanese immigrant in the small village of Santa Lucrecia, Veracruz. That was where he married María Hernández, and where Alejandrina was born in 1933, followed by Rosita two years later.

After working for several years in the store, the Urano family moved to Las Choapas, also in Veracruz state. There, a British company, El Águila, developed an oil field that quickly attracted a large number of workers. It was probably for that reason that Yashiro decided to open his own business there, selling fruit. Every day he drove a wagon to the oil field entrance with a heavy load of oranges and other fruit sprinkled with chile, to the delight of his customers. He also sold snow cones (shaved ice) flavored with sweet fruit syrup, which quenched the oil workers’ thirst and helped them tolerate the heat.

When the war started, the Urano family was ordered by the authorities to move to Mexico City and they made the trip by train from the port of Coatzacoalcos. The Urano family’s stay at the Kyoei-kai offices didn’t last long, however. In addition to the offices, the Committee set up temporary dormitories in the same two-story house, but there weren’t enough beds for the hundreds of people who arrived. As a result, in mid-1942 the Committee decided to look for a place where the relocated families could not only live but could work and support themselves.

Teiji Sekiguchi, Makoto Tsuji, and Sanshiro Matsumoto were given the task of searching for a place with those characteristics. They visited the states of Michoacán and Guanajuato, but ultimately decided to purchase the former Temixco Hacienda in Morelos state. The hacienda was an ideal place to grow rice and vegetables, both because of its 250 hectares of land and its abundant supply of water. The payment made to the owner, Alejandro Lacy Orcy, totaled 180,000 pesos, and came from contributions from the Japanese embassy as well as funds the Committee had raised.

The relocated families who weren’t able to find a home and work that would enable them to make a living in Mexico City decided to move to the Temixco Hacienda. Despite these terrible circumstances, the arrival in Temixco was a happy time for Rosita Urano. Temixco’s heat and exuberant vegetation reminded the young girl of the land where she was born. She was just seven years old at the time but remembers it as vividly as if it were yesterday, even though 75 years have passed.

The Urano family and close to 600 other people quickly began working the land in an effort to settle as best they could. The most difficult part was building dormitories where they would all have to live during the war. They built the dormitories themselves with wood, and while one section was reserved for families, the other was only for single men.

Men of working age went to the fields early in the morning, usually by 4 a.m., and earned 4 pesos a week for their work. To coordinate activities at the hacienda, the Kyoei-kai appointed an administrator, Takugoro Shibayama, who lived there with his family until the end of the war. Outside the hacienda, the DIPS posted two soldiers at all times to guard the entrance.

The families also built a dining hall at the hacienda where three meals were served each day. Rosita’s mother María, along with the other women, prepared the meals; they rang a bell to announce that meals were ready and everyone gathered to eat together. Each woman was assigned to cooking duties every other week. During the weeks she did not work in the kitchen, according to Rosita Urano, her mother María sold snow cones with fruit flavors such as tamarind, lemon, and black currant just outside the hacienda.

A school was established for the children, with a Japanese teacher who taught them to read and write in their parents’ language and also gave them math lessons. Rosita’s older sister attended school in the afternoons, since in the mornings she had to take care of her little brother. Rosita, on the other hand, attended a public elementary school located outside the hacienda in the mornings and afternoons, and that is where she first learned to read.

In May 1944, Yashiro Urano requested permission from the authorities to move to the town of Jojutla in Morelos. Arturo Kisaka, a Japanese immigrant who had become a Mexican citizen, offered Yashiro a position as foreman on his ranch there. In early August, DIPS granted permission for him to leave Temixco and begin living in Jojutla with his family.

The persecution of the Japanese community is not well-known. The hysteria that arose as a result of the war with Japan dramatically altered not only the lives of members of the Japanese community but their children as well, all of whom were Mexican citizens. In September of this year, Rosa Urano will celebrate her 83rd birthday. She has yet to receive a convincing explanation of why she was forced to leave her home in Las Choapas and move to Mexico City. Without a doubt, the Mexican government owes a public apology and reparations for the damages that this action caused to Rosa Urano and hundreds of families.

For now, raising awareness about this dark period in Mexico’s history will enable us to continue to be vigilant and ensure that similar violations of the human rights of thousands of citizens never happen again.

© 2018 Sergio Hernández Galindo