Kara Matsushita Kondo was born in Wapato, a town with a thriving Japanese population. There were Japanese-owned businesses and schools, a Buddhist church and a meeting hall. The Wapato Nippons baseball team won a pennant and a following beyond its local fan base.

But she knew that her life would change in the aftermath of Dec. 7, 1941.

“We were very uncertain what would happen to us, and we realized it would never be the same,” Kondo recalled in a brief recorded oral history that can be heard at the Yakima Valley Museum. It’s among several oral histories of immigrant experiences in the region.

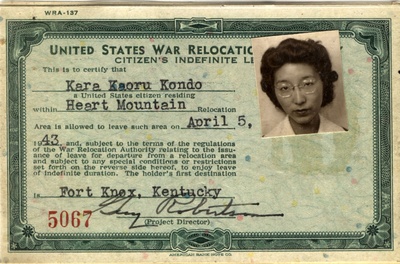

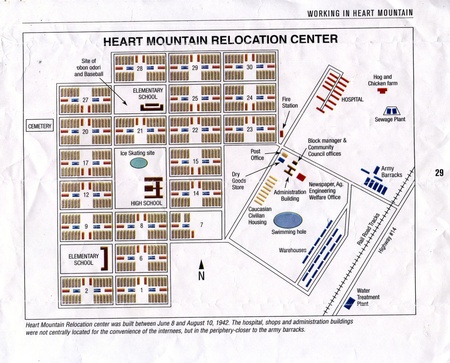

Kondo, who died in 2005 at age 89, left a long legacy of community service and civic activism that inspired an annual luncheon in her name. Her contributions included talking to countless students about her experience living at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming. She was among about 14,000 Japanese-Americans interned there, and she never forgot the dust, the cold and the wind, a friend said in a news story summarizing her life. But she wasn’t bitter.

“I can still remember the gate clanging behind me,” she said of her family’s arrival in the summer of 1942 at an assembly center in Portland on the grounds of the Portland Livestock Exposition. Each family lived in a converted animal stall in one of the exposition’s livestock buildings for three months before they were taken to Heart Mountain.

President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942. Approximately 120,000 Japanese-Americans were interned in camps for the duration of World War II.

By that time, some leaders in the Yakima Valley’s Japanese-American community were already gone, having been detained and taken to a location in Texas in the first few weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Others were detained the same month Roosevelt signed the order.

“Our father was an alien, so he was picked up by the FBI in February 1942,” said Dave “Minoru” Sakamoto of Wapato.

His mother became the head of the household, which at that time included her mother, three of her brothers and her five children. “She was tough,” said Sakamoto, 81.

By May 1942, most Japanese-Americans in the Valley knew they would be leaving. They could take no more than two bags with a combined weight of 100 pounds — whatever they could carry, said Lon Inaba, 61, of Wapato.

Just before boarding two trains to Portland in early June, they collectively sent a letter, signed “Valley Evacuees,” to the editor of the Wapato Independent.

“We, Japanese evacuees of this valley, are extending our hands in farewell to all our faithful friends, who have done their part in making our departure from all our life’s work less miserable,” it read.

Among other sentiments, they expressed hope that the war would be over “very soon” and that they would be reunited with their American friends.

“We extend our gracious thanks to those in the office and those appointed by the government who patiently aided us in completing our preparation for this evacuation,” the letter concluded.

A total of 1,051 Yakima Valley Japanese boarded two trains for the Portland Assembly Center.

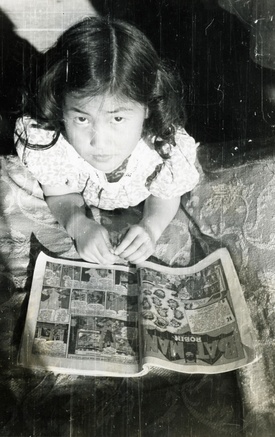

Sakamoto was 7 when his family arrived at Heart Mountain. His father joined them in 1943, a little more than a year later.

“He was in ... an immigration camp in Missoula, Mont.,” Sakamoto said. “So there were Italians, German nationals, Japanese.”

Valley resident George Hirahara set up a photo studio at Heart Mountain, chronicling its families and their activities. There were dances and Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops. Artists re-created their surroundings and crafted other artwork.

Sakamoto played eight-man football and joined friends for visits to the Shoshone River. Monitored by lifeguards, they swam in a swimming area that resembled a gravel pit. His father worked at the camp as a carpenter.

“For us it was play. We didn’t have to really work,” Sakamoto said. Three of his siblings were born at Heart Mountain, he noted.

Japanese immigrants began arriving in the Yakima Valley in the early 1900s, creating communities in Wapato and Yakima. Of those interned at Heart Mountain, only about 10 percent returned. Many at Heart Mountain were from California; Valley residents developed lasting friendships with them and chose to resettle there, or in Seattle or Portland.

Their children didn’t want to be farmers, their property had been leased and they didn’t feel welcome. The FBI accompanied the first family to return.

“We found ‘No Japs Wanted’ signs in most stores in Wapato,” Kondo recalled after her family returned.

Concern with the status of Sakamoto’s father continued in the wake of the family’s departure from Heart Mountain. They still faced possible deportation because of his alien status.

“My mother resolved that if anything should happen, we were going to stay as a family,” Sakamoto said. “It was very, very hard for my mother.”

His father died in 1952. Sakamoto is past the anger, he said.

“It’s something that happened a long time ago.”

*This article was originally published by Yakima Herald-Republic on December 5, 2016.

© 2018 Tammy Ayer