What do you remember about life in the camps e.g., eating? Toilet? Baths? School? Your mother passed away there. Was she also buried there?

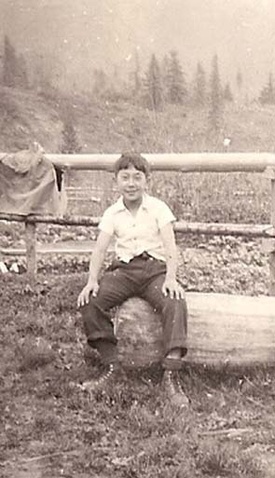

I experienced my first train ride from Vancouver (Hasting Park) to Slocan City, a four-day trip. Quite exciting for me – for mother and sisters, tiring and exhausting with only sandwiches to eat. We arrived in Slocan City in the fall of 1942. There were no living quarters available. Some families whose husbands or sons had arrived earlier to build houses for the arrival of their families were able to be put-up almost immediately.

So when your sister became the matriarch, how did life change for the Arima family? What did she do for work? After the camps?

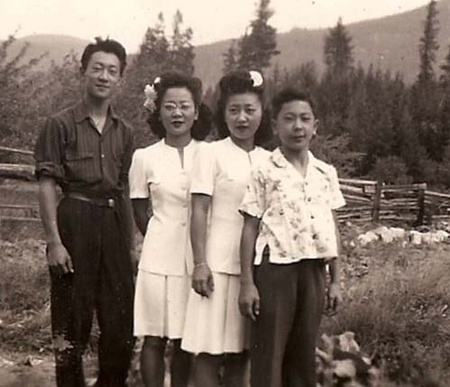

After the death of our mother in 1944, our eldest sister Takako, at the age of 22 became the sole decision maker for our family with the burden of responsibility on her shoulders.

After arriving in Hamilton from the ghost town, sisters Takako worked as a seamstress at a small dress shop and Toshiko worked at Cornell Tailors, a menswear factory which was making army uniforms and men's suits. Brother worked at various jobs, encountered discrimination in many places when he applied for a job. I was still in school.

With the loss of both parents, eldest sister Takako believed that keeping the family together was extremely important, making sure we celebrated together birthdays, picnics, holidays, etc. and even to the extended families. She maintained this well into her nineties.

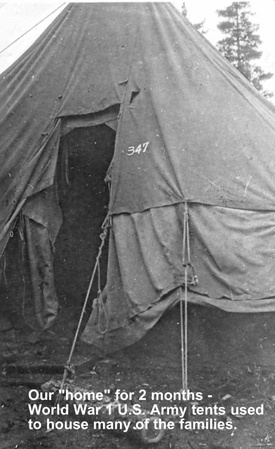

To accommodate families without housing, World War One Army canvas tents were set up. Winter was setting in and the tents had no heaters, only coal oil lamps for lighting. Bunk beds were supplied and our family of five slept in the tents for a couple of months. It was cold, I could remember our tent collapsing in the middle of a cold night and all of us trying to erect it back. For our meals we all gathered at the local ice rink which was used as a mess hall. If memory serves me, the different foods were in individual galvanized tubs.

When a cabin finally became available, thanks due to a family carpenter friend, our family was able to move in. There was no insulation, only tar paper inside the walls, with nails protruding through the wood, In the winter the nails were ice tipped it was so cold. A wood stove was our only means of heat. There was no water or electricity. Our toilet was a one-seat outhouse which we shared with two other houses, located in the back of the house. Wood-burning Japanese bathhouses (ofuro) were built and we were able to bathe. Schooling was not available till September of 1943 so I had missed school for over a year and a half with all the moving and upheaval.

In August, 1944, I was 13 years old when my mother passed away. She became very ill – and with no proper medical facilities in Slocan, she was taken to the New Denver Sanitorium (a TB hospital for the Japanese) 'though she did not have TB. With early and proper medical diagnosis she may have survived, but died a week after she was admitted. The traumatic events of the evacuation most certainly contributed to her early death. My sisters, brother and I had now lost both our parents.

Her funeral was held in Bay Farm at the Buddhist Church. Her body arrived from New Denver in a makeshift hearse (the indignity of it all – my mother deserved better). The coffin was a wooden box covered with a light gray cloth material. A bitter, heartbreaking and unforgettable moment in my life. Her body was sent to a crematorium in Nelson, BC and her ashes were returned to us and is now buried along with our father’s ashes in Hamilton, ON where my sister Takako resides.

What was the path to Toronto? Where did you first settle? Was the racism different in Toronto than in BC? Where did you go to school?

After moving from Slocan, BC to Hamilton, Ontario, I started Grade 8 at Tweedsmuir Public School. Going from a school of all Japanese kids in the ghost towns to an all white kids was a scary transition. I was the only minority in the class and feeling the stares (my imagination?). At recess one of the kids in my class came up to me and asked: "What are you...?” I stammered I was Japanese...Canadian! I don’t think my answer pleased him.

The other incident that stands out in my mind and made me feel different from the rest of the class was my first day at school. My homeroom teacher Miss Law always wore a black dress with a white collar, reminding me of someone’s grandmother. She asked me to stay behind after class. To my surprise she asked me about my name ‘Masayoshi’. What kind of name was that?

I said it was a Japanese name. She told me that it was unpronounceable and from here on in her class, my name was to be ‘Allan’; not sure how she picked that name? I was too upset and embarrassed and never told my sister. The name remains with me to this day. In today’s age this would not be possible.

Back in the early days, who did you chum around with?

In Hamilton, I became friends with a group of former ghost town guys, some I knew, others became friends and to this day we still get together. We played cards, went to Japanese teenage dances, movies, and hung out at the Pacific Restaurant drinking cokes all night.

How did you become a graphic artist? What did you really want to be as a kid? What careers did your siblings pursue?

Upon graduation from public school I attended F.R. Close Technical School in Hamilton and enrolled in the printing class because it was the only thing that interested me. Dropped out of school due to circumstances in the 11th grade and got a job at a small printing shop as a "gopher" and after one year moved to a much larger printing shop in Hamilton and started my apprentice as a compositor (one who sets metal type, an occupation that became obsolete in the digital age).

Where did you work?

After three years, I answered an ad in The Globe & Mail newspaper – hiring compositors at a firm in Toronto. In my resume, which I still have a copy of, I wrote of my qualifications and stated that I was a Japanese Canadian thinking there was a possibility of rejection as I was aware of possible discrimination.

In the summer of 1956, I moved to Toronto to start my new job. I roomed with four other friends from Hamilton who were already living in Toronto. They rented the second floor of a house in the Bloor and Spadina area. I started work at Cooper & Beatty Ltd. and at that time, one of the largest Advertising Typographic firms in North America. The majority of the largest advertising agencies (Canadian and American) had their head offices in Toronto. They were the major companies that our firm worked with.

At C&B the implementation of graphic design and its execution was the company's most important mandate and strict guidelines had to be adhered to or else! This is where my passion for graphics and design was developed, nurtured and continues to this day.

After five years I finished my apprenticeship and six years later I was promoted to work in sales. Later promoted to Sales Manager with a of a staff of 10. Stayed with the firm as Sales Manager and retired in 1996, spending 40 years with the same firm.

The career paths of my two sons, Dwayne is a computer programmer in Toronto, wife Liane and two children Kimiko and Asha. The other, Keith, works in Vancouver as a freelance graphic designer.

What part of Toronto did you settle in?

Met my wife Vi through a mutual friend and went around for 5 years, married in 1960 bought our first home in the west end of Toronto (Rexdale) in 1965.

On a level from 1 to 10, how “Nikkei” are your own kids? Grandkids?

My two sons would rate a seven and eight, the grandkids two to three.

Can you explain the low rating for your grandkids?

I think with young kids, it’s a situation that happened a long, long time ago and its relevance (although they know about it) is not on the top of their list, similar to my thoughts about World War 1 or the Great Depression.

When I first met you, you mentioned something about going into schools and talking about your internment experience and being Japanese Canadian. Can you go into some detail about what you talked about and the reaction of the kids?

On two separate occasions I spoke to my granddaughters’ classes, grades 6 and 7. They both had made presentations in school projects regarding the internment of Japanese Canadians.

I spoke of the uprooting of the Japanese Canadians. Why were we labelled as ‘enemy aliens’. Life in the internment camps. Why were we ‘dismissed’ by the school. That we had to leave our homes with only a suitcase and left everything else behind. I posted a number of photos related to the ghost town experience.

Many of the kids expressed disbelief that the Canadian government could do this to Canadian citizens. I had to assure them that this had actually happened. At the time when I was about the same age as them and that the impact of those times only became apparent as I grew older.

As the Issei have largely passed on, how do you want your own Nisei generation to be remembered by future Nikkei?

It is important for the younger Japanese Canadian generations and Canadians, in general, know the history of our incarceration and understand why it happened to prevent a repeat of the past. It's about education. Keeping the history alive.

Once my generation passes on, there's no one to tell the story, unless it's written or spoken about.

How do you feel about being of Japanese descent now after all you have gone through?

I'm proud to be of Japanese descent and in spite of the wartime experience, I am a proud Canadian.

© 2018 Norm Ibuki