I was born in Japan, and when I was eight years old my parents decided that we were going to emigrate to Brazil. We spent forty long days aboard the Sakura-maru as it crossed the Pacific Ocean, which made the distance between the two countries seem even wider. As the years went by in Brazilian lands, the issue of identity grew into something markedly present in my life: my original culture and the local one were brought face to face—sometimes they collided, at other times they drifted apart, at yet other times they merged. As a result, whether I belonged to “here” or “over there” became a question that was asked me almost on a daily basis, one that remained unanswered up until the time when I embraced this interval space as a “possible place,” filled with potentialities, mixtures, and what is rich and new.

It is a perspective that corresponds to the space-between, a “border space” that the Japanese call Ma and that is manifested in every cultural realm; for instance, in architecture, through the engawa terraces of traditional Japanese houses, areas belonging to the interior and/or the exterior, depending on how the relationship between the environments is organized. In this sense, the issue of identity is both fluid and open to the “concordance” one wants to establish among different cultures: new and diverse identities are thus constructed.

The research work of the exhibition Transpacific Borderlands: The Art of Japanese Diaspora in Lima, Los Angeles, Mexico City, and São Paulo conveys much of this experience, having begun in 2014 with a questionnaire intended for artists whose focus rested on the issue of identity. The answers generated a wide array of content. In a generic manner, one could say that Japanese Latin Americans belong simultaneously to two or more places—or to nowhere, in some cases.

The “concordance” established by artists with the political, economic, and social realms varies according to the country where they have settled: in Peru, one can easily see the importance of the Fujimori government; in Mexico, where took place the earliest Japanese immigration to Latin America, the presence of Japanese artists is strongly linked to their passion for Mexican culture; in the U.S., what the Japanese had to cope with during World War II is unparalleled; and in Brazil, which has the largest Japanese community in the world, the formation of art groups in the 1930s is an important event.

In the case of Brazil, there is a major difference between pre-war, immigrant Japanese artists who came as agricultural workers beginning in 1908, and those from the post-war period, who upon their arrival already had an artistic background from Japan. There are also those artists who are descendants of second-, third-, and fourth-generation Japanese, in whom it is possible to observe a wide range of identities: some, in different ways, have an intrinsic connection with Japan; others deny their Japanese identity; there are also those who create another Japan inside Brazil, and those who don’t feel the need to identify themselves with an ethnic group.

For the curatorship of the exhibition, three Japanese Brazilian artists were chosen: Erica Kaminishi, who resides in Paris; Madalena Hashimoto Cordaro, from São Paulo; and Oscar Oiwa, who lives in New York.

Erica and her work have a strong bond with Japan, where the artist lived during two distinct periods of her life: the first time as a dekasegi and the second as a graduate student. This relationship was permeated by the fact that she faced Japanese prejudice against Japanese Brazilians, particularly during her first stay in that country.

In the exhibition, she presents the cherry tree, the symbol of transience and spring in Japan, in an installation called Prunusplastus, featuring more than 3,000 artificial flowers inserted into petri dishes hanging from the ceiling. The artist creates a florescence of plastic cherry trees, encased in covers of that same material and that never fade away. She thus plays with both the opposition between nature and science, by juxtaposing the flowers against the petri dishes, and that between ephemerality and permanence, by replacing the characteristic fleetingness of plants with lasting materiality, something that also reveals the artist's critical gaze on this symbology so widely known in Japan and around the world.

This opposition is also found in Clouds, a four-panel artwork that combines Japanese aesthetics—the use of the cloud, a very common element in Japanese painting; the presence of golden hues, commonly found in paintings of the Kano School—with Fernando Pessoa’s Portuguese-language poem “What we see of things are things themselves” (from Alberto Caeiro's [a Fernando Pessoa heteronym], The Keeper of Sheep, Poem XXIV).

Below, I’m highlighting two fragments of the text:

The essential thing is to know how to see,

To know how to see without thinking,

To know how to see when we’re seeing,

And not even think when we see

Or see when we think.

But this (pity us who carry with ourselves our dressed soul!),

This demands profound learning,

Learning how to unlearn

At first, the poet points out our inability to see things as they are, free from all preconceived notions that accompany us whenever we look at something. Seeing a blossoming cherry tree in nature gives us a feeling of enchantment, a sense of the possibility of detachment from our thoughts, of undressing the soul ... besides, a ravishing work of art also evokes the feeling of greatness.

And the flowers, one-day penitent convicts,

But where, ultimately, the stars are nothing but stars

And the flowers but flowers,

That being the reason we call them stars and flowers

This reference to short-lived flowers is the reason Erica inscribed on the work itself or filled various spaces with the verses of the poem, something that goes unnoticed by those with a less observant eye.

Madalena Hashimoto Cordaro went to Japan a number of times to study Japanese language and art, and received a master's degree in Arts in the United States. For many years she was a teacher at the University of São Paulo’s Center for Japanese Studies, in addition to being an eminent researcher of Edo era paintings (1603–1868).

Supported by her academic experience, she also incorporates Japanese techniques and ways of thinking into her artworks, including the juxtaposition of elements, sequencing free from the concept of cause and effect, serialization, the introduction of Japanese themes, and the orihon (“accordion book”) style. Yet her recollections of her childhood and adolescence in Brazil remain present in her work, such as her memories of the Catholic faith—her family belonged to [Japan’s] hidden Christians—and the student movement of the 1960s which are found in the orihon. Photographs of friends, acquaintances, and of herself, as well as iconic Japanese and Western figures make up the artwork Thousands Faces.

Some of the techniques used in the creation of this artwork—such as collagraphy and computer graphics—were novelties at the time the author was living in the United States. The name itself, Thousands Faces, provokes a dialogue about the use of numbers in artistic creations, like Hokusai’s renowned artwork Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, while referencing the issue of serialization. For the artist, the artwork reflected not the search itself for identity, but the expression of the look of diversity—by someone who has lived in Japan, the United States, and Brazil—besides giving equal importance to the faces of every ethnic group.

Oscar Oiwa studied architecture, took part in the 21st International Biennial of São Paulo, lived with foreign artists, and decided to leave Brazil to experience the art scene in Japan, where he lived for almost ten years. That was followed by a year in London and 16 years in New York. For him, ethnicity is not an issue to ponder about, as he considers himself a citizen of the world.

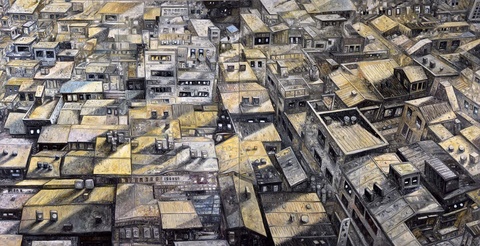

As a result, in this artist’s two artworks included in the exhibition one can see the multiplicity of that view: Crowd was created in Japan, and it is possible, while observing it, to feel the lack of space in the painting—the compacting of buildings, in black, gray, and yellow tones that produce a curious play of light and shadows. In the artwork Black Snowman, he surprises the observer by showing black snowflakes and a black snowman, thus creating a fantastical landscape by way of image clippings of the interior of homes. According to the artist, the black snowflakes are a metaphor for lead bullets, seen with frequency in Brazilian slums.

As a citizen of the world, Oiwa presents the issue of globalization or global action, a very frequent topic of discussion nowadays, and a consequence of the ease of both physical and virtual mobility, the latter through digital communications. National boundaries are erased, habits and cultures become connected, communication grows among organizational systems of thought—and these can be hybridized, thus generating new experiences, partnerships, and interconnections.

We live in a time when identification is understood as a construct across time, by way of unconscious and conscious processes, and not as something innate. In this manner, affinity has a stronger call, making it possible to belong to tribes or cultures with which one feels greater empathy, without having to be stuck with a pre-set nationality.

We return to the beginning: neither here nor there, but a Ma space consisting of a fluid and multifaceted identity.

It is this spirit that animates the Transpacific Borderlands exhibition: even though there have been exhibitions by Japanese Peruvian, Japanese Mexican, Japanese American, or Japanese Brazilian artists, so far there have been no exhibitions that have brought them all together, placing them side by side. For that reason, I believe that this is a landmark in the history of art exhibitions. And since artists tend to be at the forefront of cultural transformations, in addition to being agents in the creation of new identities, this event is a testimonial to an important moment in Japanese Latin history as seen from the perspective of the arts.

* * * * *

Transpacific Borderlands: The Art of Japanese Diaspora in Lima, Los Angeles, Mexico City, and São Paulo

September 17, 2017 – February 25, 2018

Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, California

This exhibition examines the experiences of artists of Japanese ancestry born, raised, or living in either Latin America or predominantly Latin American neighborhoods of Southern California.

© 2018 Michiko Okano