WAPATO, Wash. —Growing up in Hawaii, Frank Iseri mastered the physically challenging responsibilities of a farmer. He rigorously honed that fitness in his spare time.

“My dad was awful strong,” said his son, Eddie Iseri of Zillah, noting one competition his father relished. “In Hawaii, they would have a race (where participants would) carry a 100-pound sack of rice.”

The hard work continued after Frank Iseri, who was born in 1904, moved to Wapato as a young man. He operated an 88-acre hop farm and trained as a sumo wrestler, joining a team of nearly two dozen boys and men who gathered for training and competition in a produce warehouse near the railroad tracks.

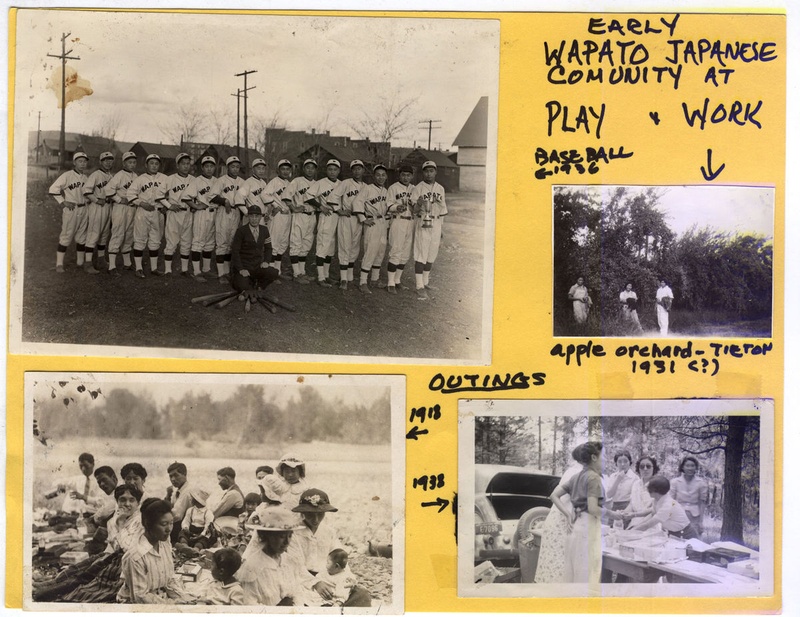

More than any other sport though, baseball brought accolades and regional attention to the Japanese communities of the Yakima Valley. Under the leadership of renowned coach Frank Fukada, the Wapato Nippons won several community league and Northwest Japanese team championships.

But as demonstrated by Frank Iseri and his fellow sumo wrestlers, those in the Valley’s Japanese communities pursued other sports with equal fervor. Eddie Iseri played basketball in the bussei kaikan, the multipurpose building next to the Wapato Buddhist Church. Dave Sakamoto and his brothers trained in judo, and several of Lon Inaba’s male relatives honed their kendo skills in the church sanctuary.

Amid busy lives centered on their families, farms and businesses in Toppenish, Wapato and Yakima, athletes and fans made time for their favorite sports. That continued even while 1,017 Valley residents of Japanese ancestry were forced to leave for Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming in 1942.

Only about 10 percent returned to the Valley and interests changed in the years afterward. The Wapato warehouse where sumo wrestlers and their fans gathered was demolished years ago. The kendo armor stored behind the church altar hasn’t been worn in decades. But its impact on the social fabric of the Japanese community continues today.

In a 1991 oral interview referenced in a Yakima Valley Museum exhibition, Isao Fujimoto talked about baseball’s legacy.

“The (Yakama) Indians had their baseball team and the Wapato Japanese had their two baseball teams. So they would play among each other,” he said.

“I would say that baseball was a pretty important way to bring people together. One of the vivid memories I have about growing up in Wapato is watching the Indians and the Japanese baseball teams.”

On Sundays during baseball season, players and fans started and finished their chores earlier than usual. Business owners closed earlier than usual. Everyone wanted to clear their afternoons for Wapato Nippons and Wapato Yamatos games, which began at 2:30 p.m.

Baseball is prominent in Land of Joy and Sorrow: Japanese Pioneers of the Yakima Valley, the ongoing Yakima Valley Museum exhibition that tells the story of the Japanese families who settled here and their descendants.

“The immigrant community’s involvement with baseball began in 1926, when Wapato’s Issei elders created Yakima Bar Nihonjin Seinenkai (the Yakima Valley Japanese Youth Club) as a way to help their children get together and socialize,” according to exhibit text notes. Originally intended as educational, it soon became an athletic club.

The Wapato Nippons baseball team formed in 1928. It joined the Mount Adams Baseball League in 1930 as one of just two non-white teams in the 12-team league. The other team was the Yakama Nation’s Reservation Athletic Club.

The Nippons in 1933 ended the season tied for first place in the Mount Adams League. That summer, players joined Japanese teams from throughout the Pacific Northwest for the annual Fourth of July tournament and won the Northwest District Japanese Baseball Conference championship.

They won the Lower Valley division title in 1934 before beating upper division Wiley City in the playoffs, earning the Mount Adams League Championship trophy. They won the league title again in 1935 and joined the Yakima Valley League in 1936; the Yamatos, a new Wapato Japanese team, replaced them in the Mount Adams League.

All this happened amid the mundane work of everyday life. Baseball players practiced once a week, on Thursday evenings. The Wapato General Store was their home game locker room.

Coach Fukuda, hired with wife, Hatsue, in 1931 as teachers at the language school, died in 1941. After the regular baseball season ended, Japanese players from throughout the Northwest gathered in Wapato to play several games as a tribute to him.

“These were the last games the Wapato Nippons would ever play,” the museum exhibit notes.

While Dave Sakamoto didn’t participate in sumo — he chose judo, a sport that continued in the Valley’s Japanese communities into the 1970s — his father Bunnosuke was head sumo referee.

“He was in the Imperial Japanese Navy from 1923-27, when he came to this country,” Sakamoto said of his father. “This was before they had a port in Portland. Ships would dock in Astoria.”

The judo club began in the fall of 1935, training in the multipurpose room of the Yakima Buddhist Church or in the space that used to be the Rainbow Bakery, according to martial arts scholar Joe Svinth. Fundraisers and dances took place at the church and the Odd Fellows Hall, he said.

“As children we took judo, we did calligraphy. ... This was during internment,” said Sakamoto, who was 7 when he and his family were sent to Heart Mountain, where sumo continued, he said.

Sumo didn’t reach as big an audience within and beyond the Japanese community as baseball, but those who participated were just as serious, competing locally and elsewhere and hosting visiting wrestlers at a Wapato warehouse.

“They had lots of events there, probably even regional events,” Inaba said.

They also trained to reach higher levels of prowess. On Dec. 28, 1938, several men received promotion to Shodan, which is first-degree black belt. They included George Hirahara, Frank Iseri, George Mizuta, Masao Sato and Henry Ichida.

Iseri earned accolades as a sumo wrestler far beyond the Valley, Inaba noted.

“Eddie’s dad was the West Coast champion,” he said.

The sharp clatter of colliding bamboo swords, known as shinai, punctuates kendo matches. But the shouting amid the strikes is even louder as combatants seek an offensive edge with intimidating outbursts.

Kendoka — those who practice kendo — train and fight barefoot, stepping lightly and moving deliberately in mirror-like fashion, never taking their eyes from each other as they strive for a strike that will earn them a point, known as ippon, and a win.

After regular services on a recent Sunday at the Yakima Buddhist Church in Wapato, Inaba opened one of two doors framing the altar and headed into a small storage area to bring out four shinai, a pair of kote (hand guards), a single tare (waist protector) and a men (mask). Collectively known as bogu, the set of kendo armor is missing its do (trunk protector), as noted by the Rev. Katsuya Kusonoki of the Seattle Betsuin Buddhist Temple.

“This stuff (is probably) close to 100 years old. ... I haven’t seen (these items) in a long time,” said Kusonoki, 40, who grew up in Nagasaki and leads services in Wapato as a traveling minister. “My father used to teach kendo. We used to have all this equipment.”

Kusonoki took kendo as a child; the training was required as a student, he said. “I think all Japanese students still have to take judo or kendo,” he added. “Judo is more defensive. This is offensive. It’s how the samurais practice.”

Kusonoki donned the equipment as his wife, Ayano, and others watched. The hand guards were tight, but he showed how to adjust their size with the laces. He held the men over his head but didn’t put it on, noting that combatants would first put on a tenugui (head towel) before putting on the heavy helmet, which protects the face with several slender metal bars.

The bars on this men were red with rust.

Looking closely at the shinai, he and his wife translated two Japanese characters as Masakazu, which can be a name that means first son of Masa. That person may have made the shinai or donated them, they said, adding that kendo is an expensive sport.

“When I was elementary school age, the local kids would come to the temple and practice from 7 to 7:30 a.m.,” Kusonoki said.

The church is also where Valley kendo participants trained, Inaba said. Church members sat in chairs then, before pews, and moved chairs to make room for kendo, he added.

“My grandfather and my dad and my uncles practiced kendo here,” he said.

*This article was originally published on Yakima Herald-Republic on July 4, 2017.

© 2017 Tammy Ayer