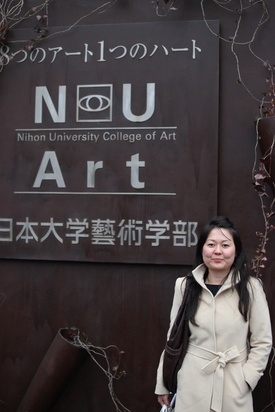

Later, you returned to Japan as a graduate student and stayed for many years, working, exhibiting, and studying both traditional forms (pottery) and contemporary forms (film and visual arts). What were some of the big lessons you took away from studying in Japan, both artistically and personally?

Going back to Japan as a graduate student made me see the country and its culture with different eyes. I experienced two situations in “two” different countries: first as an immigrant worker and then as a foreign student. The way that you’re treated in these situations changes according to your social position…well, this happens everywhere! However those two experiences gave me a more realistic perspective about the local culture and my origins too. Through my formal studies, I was able to understand certain practices and rituals cherished by my ancestors and the behavior and thinking of my parents and grandparents—to understand them and not to judge them, the way that the younger generation usually points a finger at what’s old and passé. Most of all, I believe I’ve learned to demystify and de-construct the ideology that surrounds Japanese culture. Nowadays I can observe things from both sides and this is only possible when you live and face reality and study it.

Is your family still in Brazil? Do you think they identify as Nikkei Brazilian? Do you?

Yes, they live in Brazil and today, my parents consider themselves Nikkei. Until they went to Japan, they considered themselves Japanese. My father has dual nationality. But I believe that their stay in Japan was much more difficult than mine, and the culture shock was much more complicated. They were raised and were educated as Japanese and they feel more at ease speaking in Japanese, but when they actually went to Japan they were perceived as just Brazilian immigrants, on the same level as a gaijin, a derogatory word that I heard throughout my childhood, to designate all outsiders. It’s all about experience, feeling at home in one’s own skin. Today, if they refer to a Nikkei as nihonjin, they usually quickly realize it and correct themselves on the spot.

As for me, yes I do identify (as Nikkei) and it’s visible! My looks and my name won’t let me escape the definition. However, in my opinion, this question of identifying as Nikkei or not is something that is very pertinent in Brazil and is a matter of personal experience. The definition of identity only becomes relevant or problematic in a person’s life when there is a real confrontation in a different environment or in a new situation.

Do you have a story you can share about how art became a part of your identity (either as a child or an adult)?

While I was studying for my Master’s degree, I took classes in traditional Japanese folklore, and every class was like returning to childhood, a déjà-vu through the Japanese children’s stories and songs that my mother used to tell us. This sensation of imaginary memories was very present when I went to Japan the second time. Maybe because I was more aware of the culture then. For instance, I was traveling once with my husband in the Shizuoka area, near Mount Fuji. It was my first time in that region. We decided to visit a local waterfall, which is very famous, called the Shiraito Waterfalls. When we got there, I recognized it right away!

It was such a strange feeling, like knowing it without really knowing where I knew it from. It was only later, on our way back, that I remembered “my” childhood waterfalls, which was actually a very large poster of the Shiraito, in shades of green, that decorated the living room of our house. On the poster, there was an image of a man and I remembered that I used to create stories and imagine narratives of him in this place. After that “re-encounter,” I developed a series of drawings entitled “Views of Fuji” where I make direct reference to the Mount Fuji as interpreted by artists Hiroshige and Hokusai. I reconstructed my Fuji using collages of cartographic maps of the region and poems by Fernando Pessoa:

“Cantava em uma voz muito suave, uma canção de país longíquo

A música tornava familiares as palavras incógnitas

Parecia fado para a alma, mas não tinha com ele semelhança alguma…”(She sang in a very soft voice, a song of distant land

The music made unknown words sound familiar

Sounding like a Fado to the soul, yet there was no resemblance at all)

So in a way my work is directly connected to my personal experiences. I’m not sure if I could produce anything that didn’t have this physical and emotional connection. Reclaiming those references to Japanese culture and bringing them into my work is like investigating and (re)discovering the true meaning of things that were lost so long ago. That, to me, is like being the archeologist of my own history and memory.

You discussed in your questionnaire that so many Nikkei Brazilian dekasegi bring cultural baggage with them (as I think all Nikkei do when they come to Japan and live there for awhile). Did you live in a large dekasegi community in Japan?

No, but I have visited numerous cities with large Japanese-Brazilian populations such as participate in exhibitions. It is interesting to visit these cities and the neighborhoods where there are stores that cater to the community, with Brazilian names and the green and yellow Brazilian flag on display.

Can you talk about this more or give me an example of watching Nikkei working through the complex layers of nostalgia and building their own cultural experiences?

I can’t say how or whether other Nikkei Brazilians assimilate their experience of being Nikkei into their cultural experiences while living in Japan, like I did. What I perceive is that when facing and experiencing Japanese culture there are two extremes: many identify fully as Brazilians and emphasize its national symbols: the flag, food, language, Brazilian music, etc. …or they adapt themselves fully to the local culture and become “Japanese” as a way of being accepted into society. This is my impression, but the Brazilian community in Japan is big and I believe that there is a cultural diversity, just like in Brazil.

I’m fascinated by how much you incorporate text into your work (and with pens, handwritten!). I’ve also read some of Pessoa’s poetry, translated into English. I’m curious if you have any thoughts you want to share about language? You are clearly multilingual and I’m wondering how that might affect your process at times.

I always joke that the only language that I’m fluent in is Pidgin, because I always end up mixing everything together. To be honest, I don’t know this is a good thing. I’ve always been better at writing than I am at speaking (literally), and Portuguese, my mother tongue, has always been an important part of my identity. I believe that this is true for many people, but Portuguese is the only language in which I can express myself as being “truly me.” The sensation we have when speaking other language is that of being another person…

So, since I have this difficulty with communicating verbally, writing has always been the best form to express myself. When I returned to Brazil after living in Japan for four years, writing diaries and drawing was the way that I found that helped me challenge all of my experiences and make re-adaption to Brazilian culture easier. Writing is a form of therapy, and writing repeatedly for hours is like a meditation, like in Shakyo.

What is your work and life environment like in Paris? Are you teaching in addition to creating and exhibiting work? How is your work and concepts received with this audience?

Living in France was never part of my plans. There are some things—maybe it’s fate, I don’t know—but I believe we are destined for. The way that we embrace these experiences depends on each person. My husband is French, and we met in Japan. We moved to France in late 2010, and settled in Seine Saint Denis, where French is almost like a second language, but it is convenient, because it is very close to his work. Living in the banlieue (suburbs), far from downtown Paris, has made me even more aware of my origins. I am more conscious of current political debates about immigration, ghettos, and racial borders because this is my reality today. I believe the French are more politically conscious, open to debate and are outspoken. Of course, you have all sorts of opinions here, but being in this environment has expanded my critical sense and opened me up to different interpretations of my work. I have never exhibited in France, and have always felt a bit removed from the contemporary French art scene, which tends to be more conceptual… Since I live in the suburbs, I am a bit isolated from everything. Socially it’s bad, but artistically I can concentrate, assimilate, and focus on my production. I could not produce and focus on my work if I had too many distractions.

Did you work with curator Michiko Okano to choose the piece in the exhibition? Did you have a conversation about what pieces might be the best to use in this particular exhibition?

Yes, we exchanged many emails and talked online. At first, we thought about exhibiting my Jardim work, an installation that reproduced a Japanese stone garden, and which won the National Foundation of Arts in Brazil Contemporary Art Prize. But after we studied JANM’s exhibition spaces, I proposed that we show a previously unexhibited project that I’ve kept for years and never had the opportunity to show, largely because large installations like Prunusplastus require a lot of technical planning and financial support as well. I believe the two works selected by Michiko, Clouds and Prunusplastus, were perfect for this exhibition.

What does it mean to you to be included in an exhibition of Nikkei artists?

Until arriving in LA and going to JANM in person, I had no idea of the scale of the project, or of the curatorial framework. Although I was aware of some of the historical facts of what happened during World War II, it was so intense and shocking to see the museum’s collection up close, and to meet volunteers and their descendants who were sent to American concentration camps. As I became more involved in the daily activities of the entire museum team and got to know other Nikkei artists from other countries, I began to understand the importance of a project like this! Not only for its anthropological aspects, but for its poetic sense and what it means to Nikkei as well. Being part of this exhibit will probably have a great influence on my future work.

* * * * *

Transpacific Borderlands: The Art of Japanese Diaspora in Lima, Los Angeles, Mexico City, and São Paulo

September 17, 2017 – February 25, 2018

Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, California

This exhibition examines the experiences of artists of Japanese ancestry born, raised, or living in either Latin America or predominantly Latin American neighborhoods of Southern California.

© 2018 Patricia Wakida