Return by Train to Father’s Hometown

The family stayed for about a week at the home of an uncle in Mitaka City, Tokyo. Then they made the arduous train trip to Mitsuya, the home town of Mikio’s father located near Hikone in Shiga prefecture. The train was extremely overcrowded so the trip was excruciating. Most people were standing packed close together and a few people were lying on the floor, making it very difficult to move. In fact, it was so crowded that they were unable to get off the train when it reached Kawase, the station closest to their home village Mitsuya, and they had to stay on until it reached the main station at Kyoto. Even at Kyoto it was impossible to exit through the doors, so they had to go out through the windows. Then they boarded another train and backtracked to Kawase, where a relative with a trailer cart1 was waiting to meet them.

Tensions with Relatives in Home Town

Mikio also has memories of various tensions and frictions which arose between his parents and his relatives due to the extreme living conditions in the village after the war. As they were unable to live in the main family house, they instead lived for a year and a half in a storage shed. Mikio refers to this time as their “kerosene lamp life” due to their lack of electricity and resulting dependence on kerosene fuel.

He also has specific memories of the tensions that were related to the severe shortage of food during this time. For example, once he picked a persimmon from a relative’s tree and started to eat it. Unfortunately, it tasted unexpectedly bitter, so after one bite he threw it onto the ground. The relative, extremely angry that Mikio had wasted this precious food, severely scolded not only Mikio, but also his mother, who apologized profusely. Mikio recalls that his mother, who was only 28 years old, was always apologizing to relatives during this period. Apparently Mikio’s father also had some serious tensions with his eldest brother and his wife. Mikio does not recall the details, but does remember the tension he noticed between them.

Adjustment to Japanese Elementary School Life

Mikio soon entered elementary school (Take Primary School) in Mitsuya, Hikone. He recalls that, while in Canada, his parents had done their best to teach him Japanese using various methods including singing Japanese children’s songs with him. However, in spite of their efforts, at that time he was not very interested in learning Japanese. Hence, when he arrived in Japan, he knew only a few Japanese words and was unfamiliar with the local customs, so for some time he felt quite disoriented.

Fortunately, his elementary school teacher, Miss Tanaka, took a strong interest in helping him and gave him special individual lessons after regular class hours had finished. He does not remember her explicitly teaching him Japanese, but he does recall that she spent time with him and listened to what he had to say. He told her about Canada and sang English children’s songs to her. This personal emotional support from Miss Tanaka alleviated his confusion and anxiety, and before long he began to enjoy school life.

Soon he was participating in school dramas. Specifically, he recalls participating in the school festival where he played a role as a dancer in The Monkey’s Cage (お猿のカゴ屋)、and also the role of the monkey in The Battle between the Monkey and the Crab (サルカニ合戦). From this time on, his Japanese ability improved rapidly while he gradually forgot his English. Another school memory is that they had printed textbooks, but some parts which were about the emperor or were deemed to contain nationalist propaganda were crossed out with black ink or covered over with thin paper.

He does not recall any overt bullying by his classmates over his language or cultural shortcomings, but does recall being teased and called a girl because he was wearing a red sweater. He was also laughed at because his lunch bentos consisted mainly of sweet potatoes (his preference), while those of the other children were mainly rice.

Overall, he does not remember feeling particularly troubled during his adjustment to Japanese life and thinks that he adapted and learned the language fairly quickly. He attributes this largely to the fact that he was just under 7 years old when he arrived in Japan.

Secondary Education, Conversion to Christianity

In 1948, Mikio’s family moved to Otsu city where he completed elementary school at Nagara Primary School in 1952. He then graduated from Ojiyama Junior High School and Zeze Senior High School. He belonged to the baseball teams at both schools, and remembers wearing number 11 at Zeze where he “was a benchwarmer”. That year Zeze was very strong and participated in the Koshien Spring Tournament.

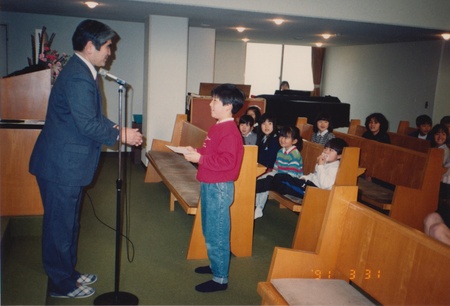

He recalls an important life decision during this period (at the age of 17), namely his conversion to Christianity. At the time he was experiencing various anxieties about his present situation as a high school student and his future life course. One day he saw a leaflet advertising an evangelistic meeting at the Otsu United Church, so he attended and listened to the sermon. Soon he converted to Christianity and was baptized. He now believes that this conversion experience was partly the result “of the seed planted” by the teachers during his 3 years at the Anglican kindergarten in the Slocan City internment camp. Ever since his conversion he has continued to be actively involved in the Japanese United Church.

He also met his wife Kana Ikeda at the Otsu United Church and they married on May 1, 1966. She is an organist. They later moved to Okamoto in east Kobe where they became members of the Okamoto United Church.

Interestingly, Mikio, who has such pleasant memories of his days as a student of the Anglican kindergarten in Slocan City Internment camp, now regularly volunteers in the church’s kindergarten.

He and Kana have two daughters, one of whom is married and has a teenage son and daughter, and who is living with Mikio and his wife.

Post-Secondary Education at Doshisha University

Mikio did well academically in high school and was accepted into the Economics Department of Doshisha University, one of the most prestigious private universities in western Japan. He credits his mother with playing a very significant role in his successful elementary and high school education. He recalls her attending his university entrance ceremony and his feeling at that time that this was the best present he could give her. He recalls making some close friends among his classmates, and regrets losing contact with two of them, Kota Otsuka and Ikuo Ebata, who went back to Canada after graduating from Doshisha University.

Note:

1. This kind of trailer cart, called a rear car (リヤカー) in Japanese, was commonly used to carry various kinds of loads before automobiles became common in Japan. It was usually pulled either by a bicycle or by a person on foot.

* This series is an abridged version of a paper titled, “Life Histories of Japanese Canadian Deportees: A father and son case history”, first published in The Journal of the Institute for Language and Culture (Konan University), March 15 2017, pp. 3-42.

© 2018 Stanley Kirk