Mikio Ibuki is a good example of those Nikkei exiles who intended to return to Canada but ended up staying in Japan. He was born in Vancouver on January 1, 1940 as the first child of Suejiro and Mitsue Ibuki. As mentioned earlier, he has a younger sister, Kazuko (born July 9, 1942 in Slocan City), and a younger brother Toshiaki (born November 3, 1944 in Slocan City). He himself was only 2 years and 6 months old when his family was uprooted from Vancouver, so he has almost no memories of his life in Vancouver before that, except for a very vague memory of watching a moving train and his mother worrying about him getting too close to it.

Uprooting and Life at Slocan City Internment Camp

His family was suddenly uprooted from Vancouver and incarcerated at Slocan City Camp from July 1942 to September 1946. As mentioned earlier, at first his father was briefly sent to a road construction camp, but was soon allowed to join his wife and small son at Slocan due to her pregnancy with their second child. Mikio has only a vague memory of watching the scenery from the train as it travelled from Vancouver to Slocan City. However, he has many vivid memories of his experiences as a small child in the camp during the following almost 4 years. He says that although his parents must have been suffering emotionally from their uprooting and the confiscation of their property, they did not pass on their anguish to their children, so most of his memories of this period are pleasant, heartwarming, and in some cases, amusing.

Many of his happiest memories relate to attending a kindergarten in the camp run by teachers from the Anglican Church. These memories have been kept alive by the various mementos that he still has from his kindergarten days. They include official portrait photos of his kindergarten class and photos of kindergarten events such as graduation ceremonies, Christmas pageants and other class activities. He also still has some pictures he drew and handicrafts which he made in the kindergarten, as well as some Bible story lesson pamphlets and Bible story pictures which he received from his teachers. He nostalgically remembers being taught common children’s songs such as “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” and religious children’s songs such as “Jesus Loves Me This I Know”. Although he does not have clear memories of specific interactions with any particular teacher, his general recollection is that the teachers treated him very kindly, and this left him with a very positive and warm impression of non-Japanese Canadians and Christianity, which continued long after he left the camp.

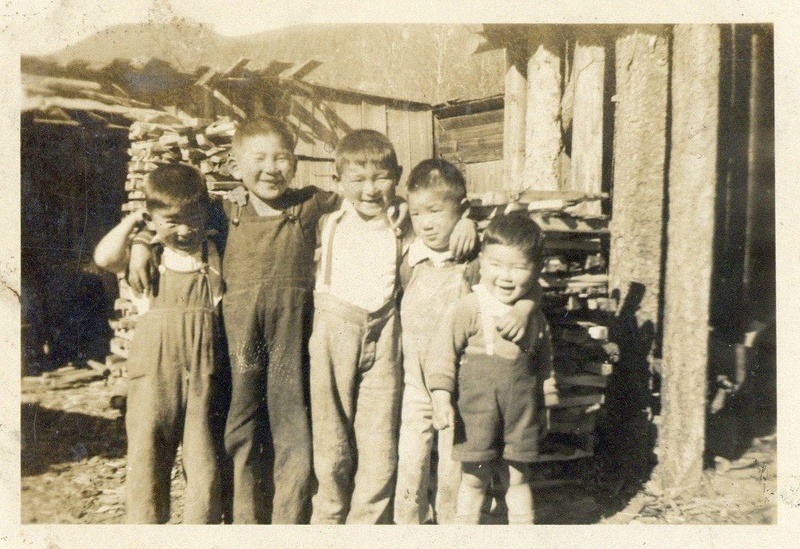

He also has pleasant memories of making many friends with other children in the camp and playing outside with them. Manabu Murakami and his younger brother Tsumoro, who lived in the same building (#12) were his close friends. He recalls various activities with them such as making a fire on the river bank and roasting wieners. They also got into mischief together. Once they entered an empty house and searched for anything worth taking. Another time they entered an empty train that was stopped at Slocan City and peeled the rubber lining from a window and used it to make a slingshot. Apparently they successfully shot a sparrow with it. Mikio took the sparrow to his mother as a present, was severely scolded by her, and then buried it.

Various recreational and sporting activities were also a big part of his life in the camp. Once he injured his arm while wrestling with his friends and cried loudly while being taken to the hospital, thinking the arm was broken. Fortunately, it turned out to be a minor sprain and healed quickly. Although he himself did not own ice skates, he was loaned a pair by an older friend. He has a picture of this, in which he is sitting on the edge of what appears to be a simple outdoor ice rink, holding a hockey stick and wearing skates that are clearly much too big for him. He is obviously very happy as he is smiling broadly in the picture. However, he does not recall actually playing hockey, or even watching hockey games. He also has memories of sleigh riding and watching baseball games although he did not play much baseball himself. Incidentally, after the war, the Murakami brothers moved with their family to eastern Canada. Mikio really wanted to meet them again but unfortunately completely lost contact with them.

Mikio also has many memories of the beauty of nature around the camp; for example, small colorful flowers, ferns and pussy willow bushes growing luxuriantly in a swampy area near the lake. He recalls catching minnows with a net and taking them home in a bucket, and leaving the bucket near the doorway. The fish soon died and started to smell bad. After a severe scolding from his mother, he carried the bucket of dead fish outside and buried them. He also remembers trying to catch reddish-colored fish1 with his hands in the river near the camp’s movie theater.

He vaguely remembers his younger siblings’ births during the internment. As mentioned above, his sister, Kazuko, was the first baby born to Japanese Canadians in the Slocan City camp. He recalls the special celebrations that followed her birth. He also remembers the time of his brother’s birth and looking out the window of the hospital.

As mentioned previously, his father did various kinds of work in the camp, including cleaning chimneys and leadership of the camp members’ self-governing committee. Mikio remembers occasionally being allowed to accompany his father to some of his various jobs in the camp.

Deportation and Boat Trip to Japan:

Mikio does not have clear memories about the end of the internment or of the train ride back to Vancouver to board the ship for Japan. However, he does recall seeing many large wooden boxes and trunks that his father had packed with food and other goods to be distributed in his home village.

He has a few negative memories of the trip by ship to Japan. For example, he vividly recalls noticing a white lady handing out balloons to some white children on the ship’s deck. When Mikio approached her for a balloon, she coldly refused and said that the balloons were “not for Japanese children.” This is his only memory of being overtly discriminated against because of being Japanese, but it was an experience that he never forgot.

Some other memories relate to his observations of his mother during the trip. Apparently she suffered for several days from severe seasickness. He also recalls first seeing the contours of the Japanese islands in the distance and many small fishing boats, and his mother shedding tears as they neared port. As they disembarked, they noticed a brass band performing a welcoming ceremony. The passengers at first thought it was welcoming them, but later learned the ceremony was to welcome Elizabeth Vining, who had come to Japan to serve as the private tutor of the crown prince.

The Situation Immediately after Arrival

After disembarking, the Ibuki family entered a temporary lodging at the repatriation center. Although a year had passed since the war ended, there was still destruction everywhere. Mikio remembers seeing and playing on the nearby remains of destroyed military vehicles and large artillery. His sister became ill and was given okayu (soft-boiled rice) to eat. Mikio also really wanted some okayu but was refused because there was too little, and it was reserved for sick persons. He can’t remember what food they did receive there, but he does recall that it tasted so bad he couldn’t eat it. Fortunately, his father had packed and brought from Canada a lot of foods and sweets to give away, and for some time Mikio’s diet consisted largely of chocolates provided by his father.

One pleasant memory of this time was being allowed to ride together with his father on an American military jeep and being driven around and seeing various places, including the ruins of Nakajima Airport and Yokosuka Port. Apparently this opportunity arose because his father was the group leader of the Japanese Canadian passengers and was summoned to the military headquarters to be debriefed by the officers.

A very moving memory concerns the emotional reunion of his mother with her father. A small festival and outdoor market were being held at a nearby a shrine. Mikio recalls going there with his mother and buying a small piece of persimmon from one of the outside vending shops, then walking down a narrow gravel street with her and suddenly meeting up with his mother’s father. This meeting was a surprise as they had completely lost contact with her family during the war. Apparently her father had by chance read in the newspaper about the ship arriving from Canada and had seen the name of Mikio’s father as the leader of the group (this was the only way he could learn that his daughter’s family was coming back to Japan), so he immediately came to find them. Mikio’s mother and her father embraced each other and cried loudly. Perhaps one reason for their open crying was the fact that her mother had passed away during the war, and this was her father’s first chance to communicate this heartbreaking news to his daughter.

Note:

1. We can speculate that these reddish fish were salmon which migrate up the rivers in this area to spawn.

* This series is an abridged version of a paper titled, “Life Histories of Japanese Canadian Deportees: A father and son case history”, first published in The Journal of the Institute for Language and Culture (Konan University), March 15 2017, pp. 3-42.

© 2018 Stanley Kirk