It was more than ten years ago that my friend Tetsuden Kashima told me of his dream project. Tetsu, a professor of Sociology at University of Washington and an incisive scholar of wartime Japanese Americans, confided that he and some colleagues had hatched a plan to persuade the University administration to offer honorary degrees to those UW Nisei students of 1941-42 whose studies had been interrupted by their wartime removal, as a gesture of healing and reparation.

At that time, no university had ever held such a diploma ceremony, but it seemed to me a particularly effective way of dramatizing the damage wrought by Executive Order 9066, not just to Nisei students, but to their universities. Tetsu added that he was looking for a theme or slogan to pitch the project. I thought it over, and then said, “what about nunc pro tunc?” Tetsu’s eyebrows shot up. “What is that?” he asked. I explained that it was a Latin term, which literally means “now for then,” used in law for rulings or decrees retroactively re-dated, as a way of correcting past errors. With that, Tetsu broke into a smile. We agreed that the diplomas offered should not only be honoris causa, in the usual manner of honorary degrees, but nunc pro tunc.

Tetsu added, “But I’m curious. You’re not a lawyer and I know you’ve never studied Latin. How did you learn this phrase?” It was then that I revealed the path I took to becoming a historian of Japanese Americans, and the place of the late Toni Robinson in shaping it. Toni played multiple roles in my life, serving at different times as my employer, my editor, my attorney/literary agent, and my scholarly collaborator. Throughout it all, she was also—and above all else—my mother.

She was born Toni Sandler in New York in 1942. Toni’s parents separated when she was a child, and she and her brother Bob were raised by their mother Joyce, who worked outside to support the family. Toni was quite precocious: by the time she was 15 years old, she had finished high school, started college, and met Ed Robinson, who became her husband two years later.

Ed and Toni Robinson would remain happily married for 43 years. However, Toni never expected to be a stay-home wife. Beyond the examples of her mother Joyce and her cousin Judy Mackey, a distinguished economist, she was inspired by Eleanor Roosevelt. In later years Toni would tell of the day when her school group visited Hyde Park and she met Mrs. Roosevelt, who spoke to them from the porch of the Roosevelt home.

After finishing college, the young bride took up various short-term jobs. One was as a writer for a children’s encyclopedia. As part of her work, Toni was asked to prepare an article on the topic “concentration camps.” Although it was 1962-1963, a time when the camps were little discussed in mainstream society, Toni’s draft included a reference to Japanese Americans and Executive Order 9066. Her editor reprimanded her over the passage and insisted on removing all such references in the final article, leaving Toni with a burning sense of injustice.

This same feeling about justice meanwhile led Toni to become interested in the African American civil rights movement. She attended the 1963 March on Washington and helped plan demonstrations. It was while protesting discrimination at the 1963-64 World’s Fair in New York that Toni was unexpectedly arrested, and spent the night in the Women’s House of Detention. The experience of seeing police lie in court and prisoners mistreated led Toni to resolve on becoming an attorney.

Before Toni continued on her career path, she and Ed decided to have children. She looked after my elder brother and me full-time during our first years. Once I started kindergarten, she went off to law school, and in the succeeding years she trained in the law, graduated with honors, and was hired as an associate by a large law firm. She later moved to a smaller firm, and was made partner. While she handled occasional civil rights cases, much of her business was in matrimonial law, representing clients in divorce and child custody cases, a branch of law that she also considered important for the well-being of society. During these years, as I was growing up, Toni was a loving parent, and despite her heavy workload and long hours at the office she found ways to remain present in my life.

At the dawn of the 1990s, when I was in graduate school, Toni left her firm and set up her own solo practice. Soon after, she was diagnosed successively with Parkinson’s Disease and leukemia. In late 1994, she underwent a bone marrow transplant. It temporarily arrested the progress of the leukemia, but she remained frail from the Parkinson’s disease. Still, Toni refused to give up her life’s work. It was clear to the family that if she was forced to retire, her will to live would be affected. I had already completed the research for my Ph.D. dissertation and started writing, but my progress was slow, and in any case I felt a higher duty to my family.

Thus it was that I laid aside my dissertation, quit graduate school and began work as my mother’s legal assistant, first on a volunteer basis and then as a full-time salaried employee. While I had done office work before, I had no legal experience, and had to learn from scratch. Luckily my training as a historian gave me a leg up in areas such as legal research and expository writing, and for the rest I could ask Toni for assistance. She reassured me that just having me around, since she could rely on me fully, was more valuable to her than any set of legal skills.

Eventually, I learned enough that I could take on tasks that would normally fall to a legal associate, such as drafting briefs and interviewing clients. This helped preserve Toni’s energy and save her clients money. Because Toni was too weak to hold a briefcase, I also literally fetched and carried for her. In the process of my work, I learned legal concepts such as pro se and estoppel—and nunc pro tunc.

The law work was rigorous. If Toni needed to work late on her cases, I would stay with her at the office —sometimes we were there until midnight. All the same, it was a great treat for me to work together with my mother, and see a side of her I might otherwise never have experienced. We became close partners, able to speak in shorthand and finish each other’s sentences. Our writing styles complemented each other, and her edits improved my prose. I even considered entering law school so that I could one day become my mother’s law partner, but it was obvious that I could not simultaneously attend school and assist her.

Sadly, Toni’s Parkinson’s symptoms eventually progressed to the point that she could no longer handle her demanding caseload. She closed her office in late summer 1998 and spent the next months working from home to wind up her existing cases, with part-time help from me.

It was while I was working in Toni’s law office that I became absorbed in studying Japanese American history. I was invited by a journal to write about Franklin Roosevelt, and decided to contribute an article on FDR’s pre-presidential writings. In the process of reading up for the article, I came across Roosevelt’s articles and newspaper columns during the 1920s, in which he had called for exclusion of Asian immigrants and endorsed discriminatory laws against Japanese Americans on the grounds that they preserved the “racial purity” of white Americans against interracial marriage.

Horrified and fascinated, I pondered the relation of Roosevelt’s racial attitudes towards Japanese Americans to his later signing of Executive Order 9066. The question grew from an article into an independent research project, until finally I decided to leave off work on my abandoned dissertation and concentrate on this new topic. Once my mother retired, I re-enrolled in graduate school and began writing a dissertation on FDR and the Japanese Americans.

From the beginning, Toni shared my fascination with these questions. She let me do research in libraries and archives during slow periods at the office, and go present my first findings at a conference. Gratified by her interest, and accustomed to working with her, I asked her to read and edit the drafts of my new dissertation once she retired. Thanks to her help, I was ultimately able to complete my research and write the body of the thesis—some 500 pages—in less than 9 months.

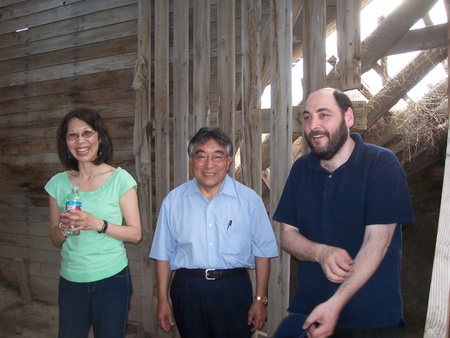

To help Toni edit my thesis, I shared with her the archival documents that I uncovered. I was intrigued by her analysis and proposed that we collaborate on a paper. Toni agreed, but asked that our relationship not be specified, as she did not wish to feel like an interloper. We decided to center on Toni’s old hero, Eleanor Roosevelt, and her conflict with FDR over mass removal. In fall 1998, just after Toni retired, we traveled to Oregon and presented together at Willamette University (my father Ed, who had also taken an interest in my work, kindly attended the conference and drove us around.)

After I completed my dissertation and had time, we began regular work together. It was an interesting education in the mechanics of collaboration. I acted as leg man collecting research, and then wrote the first drafts. Toni studied the documents and did rewriting. Sometimes we disagreed and would have to find a compromise or give in—my friend Ken Feinour still loves to tease me about watching Toni and me screaming at each other over the placement of a comma!

Our new project traced the history of relations between blacks and Japanese Americans, and their postwar alliance for racial equality. Ever since Toni’s youthful involvement with civil rights protest, she had been fascinated by struggles against discrimination in the courts. I came across information on postwar legal cases in the Supreme Court involving Japanese Americans, and Toni used her legal skill to dissect the arguments in the briefs (we were unusual in studying arguments in amicus briefs). After weeks of work, we produced an extended manuscript.

We meanwhile did a variation on the same theme when we wrote an article together about Nisei-Latino connections and the Mendez v. Westminster desegregation case, and then presented our work together at a conference at Columbia University.

In 2001, I moved to Montreal, but Toni maintained her interest in my work. When my first book, By Order of the President was published, she and my father threw me a big launch party. When I signed with another publisher to do a second book, Toni acted as my literary agent, and taught me to look over the contract and request necessary changes. We began work expanding our unpublished manuscript on Black-Nisei connections into a full-length book. Sadly, in summer 2002 Toni fell ill from leukemia, and died soon after. Our two joint writings were eventually published (and later interpolated into my book After Camp)—the journal articles by “Robinson and Robinson” remain my most cited.

What is more, Tetsuden Kashima and his colleagues succeeded in their mission, and in May 2008 the University of Washington held a special event, "The Long Journey Home,” to grant diplomas to the UW Nikkei Students of 1941-1942. As recommended, the degrees honoris causa were presented nunc pro tunc. Beyond my joy for the UW students, I take special pride in this last part, as part of the legacy of Toni Robinson to Japanese American history.

© 2018 Greg Robinson