Deportation to Japan after the Internment

Suejiro and Mitsue were among the Nikkei who agreed to be deported to Japan rather than move to eastern Canada. Mikio believes that the most compelling reason was extreme anxiety regarding the wellbeing of Mitsue’s parents in Tokyo. As mentioned earlier, there was no contact between the Nikkei Canadians and their loved ones in Japan during the war, and the resulting desperation to reestablish contact and confirm the survival and welfare of loved ones became one of the strongest motivations to accept the deportation choice. Mikio says his father also had another strong motive to return to Japan—the wish to use his experience in Canada to help rebuild a better and more internationalized Japan following its destruction in the senseless war.

In October of 1946, he and his family boarded the Marine Falcon, one of the three ships chartered by the Canadian government to deport Japanese Canadians. According to the ‘Repatriate Card’ issued to the family upon arrival in Japan, the ship left Vancouver on October 2 and arrived in Kurihama on October 15. Suejiro was the group leader of the Japanese Canadian passengers.

Although the deportees received only a modest amount of money from the Canadian government and were not allowed to bring foreign currency into Japan, Suejiro brought with him many large boxes and trunks filled with various kinds of goods (including rice and canned goods, medicines, sweets, etc.) to be distributed in his village. Obviously he had heeded the strong advice given to the deportees to take as many such goods as possible.

The ship was originally scheduled to arrive at Yokosuka, but as that port was already full, it was diverted to Kurihama. Soon after disembarking, they learned the heartbreaking news from Mitsue’s father that her mother had passed away during the war. The family entered a temporary lodging for several days, and then stayed a few more days at the home of Suejiro’s elder brother in Mikata, Tokyo, after which they went by train to Mitsuya, Suejiro’s home village in Shiga.

Problems Resettling in His Home Village

Finally they arrived in Mitsuya. Like many who returned to their home villages in Japan after the war, they soon faced serious difficulties. The most immediate one was that, due to the severe shortage of housing, they could not live in the family house but instead moved into a nearby storage shed, where they lived for a year and a half. They had no electricity, so for lighting they depended on a kerosene lamp. They also experienced friction with their relatives, partly due to the severe shortage of food. Everyone was lacking food and other basic necessities, and although Suejiro had brought many goods from Canada, they were soon used up, and some resentment resulted. Fortunately, in April, 1948, they were able to move away from Mitsuya to Otsu City for Suejiro’s employment.

Employment after Returning to Japan

Suejiro’s first job after returning to Japan was as an assistant managing director with Hokoku Sangyo Ltd., a textile company in Nagahama City which was managed by his nephew. After one year (1947) he was able to get employed as a Labor Liaison and Advisor by the Labor Section of the US Armed Forces at Otsu City. This position involved him in the hiring of Japanese workers for the base, which employed a total of 6000 Japanese civilian workers, and it enabled him to help many of his relatives and friends get employment there. He studied hard about various aspects of his job, but he was handicapped by his lack of a college or university education, and this limited his advancement (This hardship later led him to make sure his children got a good university education). He was transferred to Nara in 1957 where he continued working until the US Armed Forces closed its camp there in 1958.

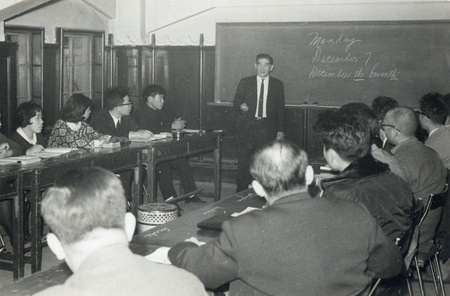

The following three years were quite difficult for him economically, but he did engage in various kinds of jobs including sewing machine sales, and established a small English school which continued for 3 years. He also started to teach English conversation lessons to many people of all ages at Otsu City Hall, which continued for 35 years. These jobs helped provide money for his children’s education. He told Mikio that, from the time he returned to Japan, he strongly felt that teaching English was the best way he could help Japan become an international country and contribute to mutual understanding and world peace.

His economic situation significantly improved in 1961 when he was employed by Jinbo Pearl Ltd., to which he had been introduced by his elder brother’s daughter who was married to the company’s founder. During the following years the Japanese economy was improving, and his career in the pearl industry went well. He soon began to work at a subsidiary pearl exporting company, Jinbo Pearl Exporting Ltd., located in Kobe. His son Mikio joined him in this company in 1962. Six months later, Suejiro moved to the company’s pearl farm in Shiga and continued to work there for 6 more years. Then, at age 60, he started his own company in Otsu City, Jinbo Shinju Shokai Ltd., which retailed fresh water pearls from Lake Biwa. Many of the pearls were supplied by his son Mikio who continued to work in the pearl export company. Mikio recalls that this was a very enjoyable period of Suejiro’s life. Incidentally, his company is still active and is managed by his younger son, Toshiaki.

Continuing Contact with Canada

Suejiro apparently regretted his decision to return to Japan, and he often apologized to his children, saying that it was a mistake. He continued to stay in contact with his friends in the Nikkei community in Canada. In addition to personal correspondence and sending Japanese magazines to various friends in Canada, he occasionally contributed to Japanese publications in Canada.

Interestingly, although he encouraged his children to move back to Canada, he himself never returned to Canada, even for a visit. Mikio is not sure why, but speculates it might have been because he did not wish to be reminded of what he had suffered there. However, in a brief profile based on an interview conducted by Art Miki and published in the Nikkei Voice (November, 1989), he mentioned that he hoped one of his children would move to Canada so that he himself would be able to go and visit, so it is clear that he at least thought about it. His wife Mitsue did visit Canada once with their daughter for two weeks in the autumn of 1994 at the invitation of her niece’s daughter who was living in Toronto. In addition to Toronto, she went to Vancouver and visited one of the apartment buildings where they had lived before the internment. It still looked the same as when they had left it at the time of their uprooting, and she was moved to tears.

On February 17, 1995, Suejiro passed away at the age of 87. His wife Mitsue passed way 8 years later at the age of 83, on November 5, 2002.

* This series is an abridged version of a paper titled, “Life Histories of Japanese Canadian Deportees: A father and son case history”, first published in The Journal of the Institute for Language and Culture (Konan University), March 15 2017, pp. 3-42.

© 2018 Stanley Kirk