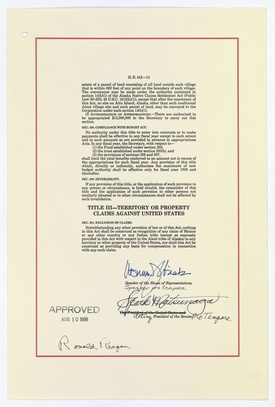

It took just seconds for U.S. President Ronald Reagan to sign the document. Yet the journey to that moment spanned more than four decades.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was the culmination of a multiyear movement to seek justice for Japanese Americans forced to live in wartime concentration camps solely because of their Japanese ancestry. After Reagan signed it into law, the Act granted reparations of $20,000 and a formal presidential apology to every surviving U.S. citizen or legal resident immigrant of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during World War II.

The act cited “racial prejudice, wartime hysteria and a lack of political leadership” as the causes for the mass-incarceration. It also rejected the government’s original rationale that Japanese Americans posed a significant national security threat, noting that the incarceration was “carried out without adequate security reasons and without any acts of espionage or sabotage.”

As a legal precedent, the Civil Liberties Act has often been cited for comparisons to issues in the present day.

“Japanese Americans have an intimate and uniquely informed perspective on civil liberties,” says John Esaki, Vice President of Programs, at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM).

“Having been deprived of our constitutional ‘guarantees’ during World War II, we have a responsibility to convey the lessons of the incarceration of our community to current and future generations, to help them confront and resolve similar issues that face their own communities.”

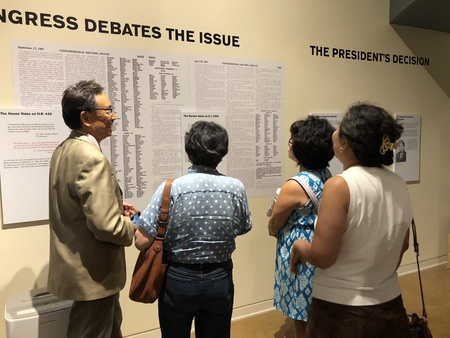

In commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the landmark legislation, JANM updated its long-running core historical exhibition, Common Ground: The Heart of Community in August. Artifacts related to the redress movement from JANM’s permanent collection were added and original pages from the Civil Liberties Act document were on display for a limited time, on loan from the National Archives in Washington, DC. (The original pages have since been replaced with replicas.)

“Through the generosity and cooperation of the Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, we also have on display for a limited time the pen used by President Reagan, Senator Spark Matsunaga, and Congressman Norman Mineta to sign the Civil Liberties Act,” Esaki says. “Thanks to the National Archives, we were able to reunite the document and signing instrument for the first time in 30 years!”

Common Ground was originally conceived to illustrate the commonalities Japanese Americans share with other communities, Esaki says. Presented as an artifact-filled timeline through history, it was originally intended as just a temporary exhibition. It quickly became very popular with teachers and schools and ended up becoming a long-term display. Since its premiere in 1999, Common Ground has been the institution’s most successful and widely viewed exhibition. Museum staff estimate that it has been seen by more than 1.5 million visitors.

“Common Ground was planned and installed 19 years ago,” Esaki notes. “On purely a technical, physical basis, labels and photographs that were never intended to be on display for more than a few years are now discoloring with age and in some cases peeling from their mounts. More importantly, the informational content also is dated, and the current curatorial team was able to take advantage of this opportunity of the Civil Liberties Act anniversary to include recent scholarly research on the resettlement era and the redress movement.”

JANM’s staff sought out scholar and historian Dr. Mitchell T. Maki to help update the section. “Mitch is the definitive source on the history of redress, having co-authored Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress,” Esaki says. “He also was the key interviewer on a series of extensive life history interviews conducted for JANM with ten key participants in the redress movement in 1998, and he organized the Voices of Japanese American Redress conference at UCLA in 1997. His involvement as a curator was critical to providing an informed and balanced view of the history and significance of redress.”

Maki is also President and CEO of the Go For Broke National Education Center, which shares space on the JANM campus. Esaki notes that when Maki was invited to participate in this project, Maki proposed an accompanying display on the role of veterans in the redress movement to be mounted in Go For Broke’s facility in JANM’s Historic Nishi Hongwanji Building.

“(U.S. Senators) Daniel K. Inouye and Spark Matsunaga were powerful and unassailable advocates for redress because they were decorated veterans who had served the U.S. with distinction during the time that Japanese Americans were being portrayed as disloyal and untrustworthy,” Esaki explains.

“When Senator Inouye (who lost an arm in battle in World War II) spoke before the Senate, even the most conservative colleagues were confronted with the reality of a true patriot who had sacrificed a limb for the U.S. Even today, service to the country through the military continues to be considered by many a patriotic demonstration of one’s willingness to sacrifice for the nation.”

In addition to military veterans, Esaki credits dedicated activists such as Yuri Kochiyama, Michi Weglyn, and Aiko Herzig Yoshinaga as other pivotal figures relevant to the Civil Liberties Act. Yoshinaga recently died at the age of 93.

“As the years—and decades—pass, you realize that there are generations of people who do not know the essential stories or the lessons of our history,” Esaki says. “There is, therefore, no point in time that you can rest, secure in the belief that all valuable information has been safely ‘passed on.’ We are determined to keep these stories alive so that they can protect people against future injustices.”

© 2018 Darryl Mori