I have the museum mostly to myself today.

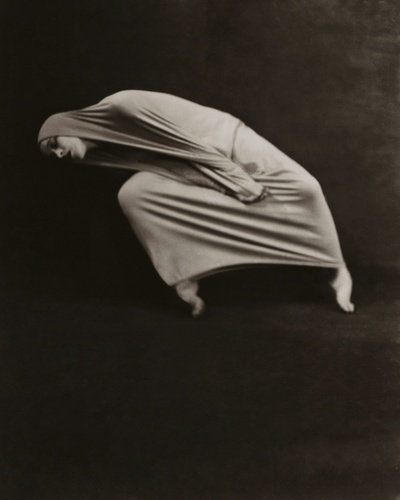

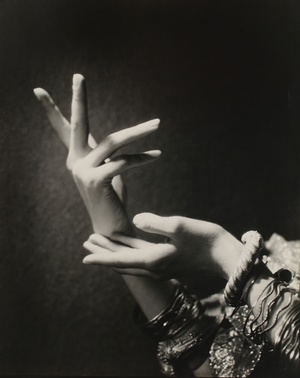

At the Cascadia Art Museum’s exhibit Invocation of Beauty, there are breathtaking portraits of famous figures of modernism, including the famous dancers and choreographers Martha Graham and Agnes deMille. There’s a room devoted to the members of the Seattle Camera Club, with mainly Japanese American members, and the “Tadama Class,” students of the Dutch artist Fokko Tadama. A series of striking portraits on the walls, many reprinted from silver gelatin originals. Another series of paintings, created by other familiar Seattle-area Issei names: Kenjiro Nomura, Kamekichi Tokita, Sumio Arima.

What has me shaking my head, today, though, are the Japanese American faces on the walls, especially the picture of the Japanese American man with a tripod camera that is the lead for the entire exhibit: a man named Soichi Sunami. Sunami’s considerable talents led him to be hired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MOMA) in New York City, where he remained its official photographer for close to 40 years. In 1945 he married a Japanese American woman from Bainbridge Island, Suyeko Matsushima, and died in 1971.

To see a Japanese American man and Japanese American artists on the same walls with these figures of modernism is paradigm-shifting. The exhibit is telling me that these Issei photographers were an important part of modernism, a cultural movement that I had mostly studied as a European and a White American one, and then to some extent an African American one as well. Invocation of Beauty reaches across barriers of language and chronology to show me that the documentation and the artistic influences of modernism owe a debt to Japanese American photographers. It’s a stunning exhibit, and though it’s a Friday afternoon at the museum, I’m the only one there.

* * * * *

My work here began with a question: “Have you heard of Soichi Sunami?”

I had not, but I was willing to learn more. Discover Nikkei reader James Arima asked me to visit the Cascadia Art Museum in Edmonds, Washington (a few miles north of Seattle). I didn’t realize this before, but James’s father Sumio Arima, former editor of Seattle’s Japanese American newspaper The North American Times, was a painter as well. Several of Sanford’s artistic works are in the exhibit. “I didn’t even know that [Sunami] was my father’s friend,” James tells me by phone. “So there are bits and pieces of revelation that we’re just getting to know now. We didn’t know he had exhibited his work in New York City.”

I then spoke with the curator of the exhibit, David Martin. Martin is Seattle-based, and heard of Sunami’s work through his initial work on the Seattle Camera Club in his co-written 2011 book Shadows of a Fleeting World. He spoke to his friend, painter Anna Kutka McCosh, who “barked at [him]” that “none of [the Seattle Camera Club] were as good as Sunami.” Martin’s research led him to meet members of the Sunami family. He tells me by e-mail that though he has known the Sunami family for 20 years, he has been trying to find a sponsoring museum for Sunami and his works for 25 years.

The exhibit also has an accompanying catalogue, both titled Invocation of Beauty. The exhibit and the book come largely from family archives, including the Sunami family collection. I wanted to hear more from Sunami’s relatives, several of whom are still living and artists themselves. My friend James Arima connected me online with Jennifer Sunami, granddaughter of Soichi Sunami, a graphic designer who lives in Seattle. She was kind enough to answer questions for me over e-mail.

Did Jennifer Sunami know about her grandfather’s work? “I think I always knew that my grandfather was an artist,” she says, “in part because my father is also an artist and he wanted me to understand our family legacy. Unfortunately my grandfather passed away before I was born, and there were large pieces of his history that I never knew until I was an adult. We had some of his photos hanging up in our home when I was growing up, and I loved looking at them, but it was many years before I understood them as art.” Seeing her grandfather’s work in the exhibit and its accompanying catalog, she says, was “a gift. Seeing the life of my grandfather told through his art on the walls of the gallery and in the beautiful book David put together was intensely moving. Here were the pieces of our family story framed into a coherent whole—it gave me a connection to the past and such a sense of pride in my grandfather's skill as an artist.”

I ask Jennifer Sunami what legacy she hopes her grandfather’s exhibit can give other Japanese Americans. “As an immigrant, he left behind his heritage in many ways, by moving to the U.S. and becoming an artist. But if you look at his work, you can see the influences of Japanese art and culture, and I feel like he always took pride in his identity even when there was incredible outside pressure to abandon his Japanese heritage and community.” Soichi Sunami escaped the World War II mass incarceration of many of his contemporaries, largely due to his connections and location, but he did destroy many of his own artistic works during the war.

For Jennifer Sunami, the roots of her family’s multiracial identity as Japanese American and Black American are in the exhibit as well. “I think my family has never been afraid to embrace the contradictions of a blended identity,” she tells me, “because it grants us a unique perspective that draws from many worlds. My grandfather's greatest successes came when he was following his own vision of what his life could be, not the constrained paths laid out for him by either Japanese or American society.”

* * * * *

I was going to leave this essay with Sunami, but there’s a lot more to say about where this journey has led me.

A few miles south from Edmonds, the same weekend I visited Sunami’s exhibit, many of my Japanese American friends and community members were visiting Contested Histories, a pop-up traveling exhibit from the Japanese American National Museum—the artifacts made even more famous recently because the Japanese American community prevented them from going up for auction back East. I was part of those efforts, using social media to call attention to the sale. When I mentioned the Sunami exhibit on social media, few of them had heard about it, but were excited by the previews I’d shown them. By contrast, curator David Martin expressed some disappointment to me: “You are the only one [from Japanese American community organizations] who has responded,” he says.

There are a number of gaps to address here. From my limited experience as a freelancer, I know that arts writing is not high on the priority list in publishing these days. Arts writing by and about people of color is also rare. I have been lucky to work with editor (and artist) Alan Lau at the International Examiner for years. We are still searching for a way to publish an anthology of 40 years of Asian Pacific American arts writing. Moreover, in a prominent East Coast-based photography magazine, Aperture, writer Will Matsuda recently wondered, “Why Are There No Famous Asian American Photographers?” He interviewed several young (all under 35) Asian American photographers, but I was struck by this highly contemporary focus which seems to be divorced from any longer history. As a resident of the Pacific Northwest and someone interested in Asian American arts and history, I knew about the Seattle Camera Club as well as visual artists like George Tsutakawa and Paul Horiuchi. But I wonder how much of that knowledge is due to region.

I know enough to know there’s a lot I still don’t know here.

So I ask my community. Friends and colleagues tell me more about names I need to know. Poet Neil Aitken tells me about Sadakichi Hartmann, Japanese-German American photographer and poet. Performance artist Anida Yoeu Ali reminds me of photographer Corky Lee. She mentions Walter Chin, who is famous in fashion photography. She mentions names I know vaguely—Laurel Nakadate, Pipo Nguyen, An-My Le, whom she considers “iconic.” My Seattle Star editor Omar Willey, another photography expert (and photographer himself) chimes in with a documentary about Chinese American photographer Charles Wong. Scholar Laura Kina and others have just begun an exciting project, the Virtual Asian American Artists Museum, and I can’t wait to see how it develops.

But this essay is also a plea for more arts writing, especially by and about people of color. I’m a part-time arts writer, part-time public historian, but not an art historian. If there is a lack of knowledge of “famous” Asian American photographers, there is also a lack of writing about them, and there is a lack of arts writers who know how to look for and ask about submerged histories. It’s ironic to me that Sunami and his contemporaries were recognized and famous in their own time, publishing and exhibiting both nationally and internationally, but are still now being “rediscovered.”

Ethnic media like Discover Nikkei play an important role, but we need to ask ourselves hard questions about community and the artist’s memory: not only what and how an artist remembers, but how our artists are remembered. A friend just posted a link to this important post by Seattle’s Frye Art Museum curator Negarra Kudumu, who reminds us: “Art writing is how the public learns about artists and their work. It’s how artists enter, advance, and shape cultural discourses. Their ability to do so heightens their cultural cache and can be connected to their commercial viability.”

In the meantime, I have the museum mostly to myself today. I’d rather not be alone there.

* * * * *

“Invocation of Beauty: The Life and Photography of Soichi Sunami” is at Cascadia Art Museum (190 Sunset Ave #E) in Edmonds, Washington through January 6, 2019. Curator David Martin is leading a tour of the Sunami exhibit from 10AM-12PM on December 16, 2018. The event is $10 for Museum members, $15 for non-members.

The museum is open Wednesday through Sunday, 11AM-6PM as well as on the Third Thursday of each month (free admission) from 5-8PM.

© 2018 Tamiko Nimura