The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 didn't just spark a war between the United States and Japan. Beginning on that day, communities of Japanese immigrants who had settled in several countries in America also became part of the conflict and hostilities.

Several governments in America considered Japanese immigrants to be an invading army of the Japanese empire, and as a result they were forcibly relocated and persecuted despite having settled in those countries decades before. The children of Japanese immigrants, although they were not citizens of Japan, were labeled “foreign enemies” in the countries where they’d been born. The Pacific War unleashed, on a massive scale, racial hatred toward immigrants, a sentiment that had been present from the time of the waves of immigration in the late 19th century.

At that time, more than 800,000 people left Japan for America in search of work and a better future. They were farmers, miners, fishermen, merchants, and professionals who built solid communities with deep roots in the towns and cities where they settled. Some Japanese immigrants even became citizens of their new countries, including Mexico. Tens of thousands wanted to obtain nationality in the United States, but U.S. laws prohibited it, based on the belief that such immigrants were of an inferior race and a threat to security.

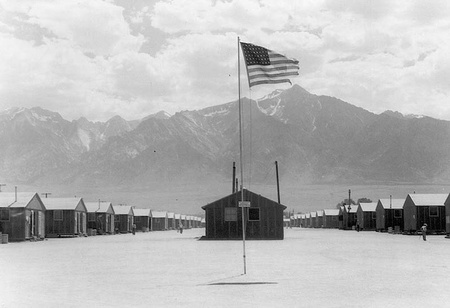

In February 1942 the president of the United States, Franklin Roosevelt, ordered the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese immigrants and their descendants, sending them to 10 concentration camps. Two-thirds of those incarcerated were children and youths who were U.S. citizens.

Under pressure from the U.S. government, Mexico, Peru, and Brazil issued their own decrees forcing immigrant families to move away from their homes to a few specific places so they could be concentrated and monitored. The most serious case was that of the Peruvian government, which practically allowed Japanese families to be kidnapped and taken to the United States. In total, more than 2,000 Japanese immigrants and their descendants in Latin America, the majority of whom were from Peru, were forcibly relocated to U.S. concentration camps.

An early atomic bomb.

Internment, monitoring, and forced relocation inflicted enormous suffering on the Japanese immigrants and their families, destroying the places they had called home. They were forced to leave jobs and the ways of life they had created, leaving the homes and property they had harvested from decades of work. Children and youths were forced to withdraw from schools and leave the places where they had grown up. For all of them, the war and the measures that accompanied it were like an atomic bomb that destroyed everything in an instant.

The Mexican government, that same month of December 1941, ordered all Japanese families living along the border with the United States to move to the cities of Guadalajara and Mexico City. With their own resources and everything they could carry, the fishermen of Ensenada and cotton farmers of Mexicali in Baja California were the first to be taken to the concentration areas. The miners of Coahuila and small merchants from Sonora and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, soon received the fateful relocation telegrams as well. Later, in all parts of the Mexican Republic where immigrants lived near the coast, they were subject to the same government orders. For the Japanese communities that had settled into life in the towns and cities of Mexico, the new year of 1942 appeared to be filled with bad omens.

Immigrant Organization and Solidarity in the Kyoei kai Mutual Aid Committee

To house and welcome the Japanese immigrants and their families to Mexico City and Guadalajara, the existing communities created a mutual aid committee, Kyoei kai. The organizing of this committee, authorized by the Mexican government, enabled them to temporarily house the thousands of homeless immigrants and help them find jobs. The Kyoei kai were funded with resources left by the Japanese embassy in Mexico with the breakdown of diplomatic relations between the two countries, as well as monetary and in-kind donations that the same community contributed to support their fellow immigrants.

The committees in Mexico City and Guadalajara helped, to the best of their ability, support all of the families that had suddenly arrived there. Many of the interned families had no resources; nor was it possible for them to obtain work to sustain themselves. Given this situation, the Committee sought appropriate places where the families could not only live but could also have a means of support. That was how the Temixco Hacienda near Cuernavaca was acquired, so that the immigrants and their families could grow rice and vegetables and earn a salary. Close to Guadalajara, in the municipality of Tala, another settlement was set up at the Castro-Urdiales ranch belonging to Jesús González Gallo, who was the personal secretary to the president of Mexico, Manuel Ávila Camacho.

It wasn’t only the immigrants themselves who were upset by the internment measure. In the places where the immigrants had lived, townspeople sent letters to the government trying to stop the relocation measures; even some local authorities requested that they remain. The local people knew the immigrants well and considered them honest and hard-working; they understood, from their own experience, that they did not represent a threat, despite the assertions of the official propaganda.

Internment and the End of the War: A New Form of Integration in Mexico

Concentration and forced relocation represented a new challenge for the Japanese communities: a new, de facto immigration, as uncertain and complicated as the first years following their arrival in Mexico. However, the concentration of Japanese immigrants increased their solidarity and the strengthened the bonds of integration and assistance among them. The central concern of these communities in this new stage was not only that their children would have enough to eat, but that they would be educated to overcome the challenges that life would present to them. The children attended public schools in the mornings, but in the afternoons they attended five schools in different parts of Mexico City, where they learned Japanese and other subjects. Another similar school was founded in Guadalajara.

After the war ended, most of the relocated families decided not to return to their places of origin, since they had already settled, one way or another, in these large cities, and there were secondary schools where their children could receive a better education. This generation of Japanese descendants evolved into a group of professionals who lent, and continue to lend, presence and prestige to the Nikkei community today. Those unfortunate and difficult conditions were ultimately propitious in creating a new Nikkei community that integrated in Mexico, while maintaining their roots in the country of their parents birth.

Akemi Matsumoto, daughter of an immigrant who was incarcerated in the United States, wrote a poem that is inscribed on the memorial in Washington, D.C., a few meters from the Capitol.

Japanese by blood,

Hearts and minds American.

With honor unbowed

Bore the sting of injustice

For future generations.

The monument was built after a decades-long struggle by survivors of the U.S. internment camps to demand an official apology from the government. President Ronald Reagan signed that apology in 1988 and reparations were paid to the survivors.

The poem also represents the sentiments of the children of immigrants throughout America, who grew up as citizens of these countries. Unfortunately, no Latin American government has offered an official apology, so deserved not only by the descendants of Japanese immigrants but by all citizens, for the extreme violations of human and constitutional rights that were perpetrated as part of the war between Japan and the United States.

© 2018 Sergio Hernández Galindo