History

With the arrival of the steamer Kasato Maru at the Port of Santos in 1908, the cycle of Japanese immigration began in Brazil, which up until the 1940s brought in nearly 200,000 Japanese immigrants.

Most immigrants left Japan, at that time devastated by a severe economic and social crisis, for Brazil, a new and promising country that offered the possibility of employment and the opportunity to earn a fortune in a short time. Most of them intended to save money and, years later, return in better conditions to their homeland, where they would then be able to provide a better life for family members.

The reality they encountered in Brazil, however, was something else; it was markedly different from their cherished dream. They found themselves in a country of huge dimensions, with landscapes stretching further than the eye could see, but devoid of any infrastructure. An immensity of wilderness and forests, tropical climate, strange customs, language, and food; everything so different from what they were accustomed to having. Worse yet, they had to subject themselves to a work regimen nearly akin to slave labor. They went to work as tenant farmers on large coffee and cotton plantations, basically in exchange for meals and housing, without any other benefits. A veritable ordeal.

A Family of Immigrants

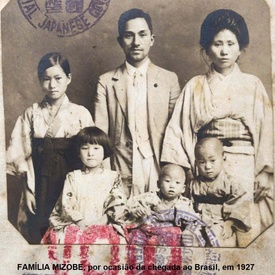

Thus lived the family of Ikuta Mizobe, who, in 1927, had landed in Santos, with his wife, Koto, and four children – Miyuki, Aiko, Tadayuki, and Takayuki – all very young and practically without any education. Only one child had remained in Japan: 9-year-old Naoyuki, whose studiousness had made them decide to leave him behind.

Mizobe-san, the head of the family, had sacrificed his job in the Prefecture of Yamaguchi, where he worked as a registrar, to leave in search of the Promised Land, Brazil, where “green turned into gold,” as it was said at the time, when Japan was in the throes of that terrible crisis.

Upon their arrival, the family was assigned to work on a coffee plantation in an area known as Mogiana, in the state of São Paulo, where they would remain until their transfer to another plantation, in the northwestern part of the state, that belonged to a fellow Japanese national who had arrived in Brazil much earlier and had succeeded in acquiring a plot of farmland.

At the end of the 1930s, Mizobe-san, at great cost, was able to buy a small plot in Bastos, a small town in the state of São Paulo with a large concentration of Japanese nationals. He relocated there with his family to devote himself to growing crops. The family expanded; three more children arrived: Tieko, Noriyuki, and Yoshiyuki, raising to seven the total number of children in Brazil.

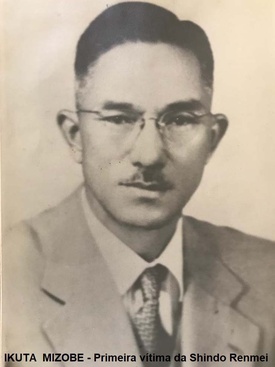

Through a lot of hard work, Mr. Mizobe managed to support his family up until the time when, in the 1940s, he was invited to take up the role of managing director at the Agricultural Cooperative of Bastos, probably due to his previous administrative experience in Japan and to the fact that he was one of the best-educated members of the local Japanese community. It was said that he was a dedicated and passionate professional, committed to the future of the Cooperative to the point of personal sacrifice; when the entity went through a financial crisis, being thus forced to delay payment of its financial obligations, he gave up his salary in favor of the employees. As evidence of his devotion to the job, each day he was one of the first to arrive and the last one to leave.

Life in the community

At the same time that the Japanese community was depicted as consisting of dedicated, serious, and hardworking people, it was perceived by locals with a certain wariness due to their notably different customs from both Brazilians and other immigrant groups. The fact that they organized themselves in cliques and showed little interest in learning the Portuguese language, in addition to their aloofness and reluctance to come in contact with Brazilians and other immigrants, accentuated the locals' distrust of the Japanese.

World War II breaks out

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the situation got worse. Japan was on the side of Nazi Germany and Italy, while Brazil aligned itself with the U.S. and other Allied nations. Three years later, in 1942, Brazilian merchant ships were sunk by German submarines, forcing Brazil to declare war against the Axis countries.

Brazil broke off diplomatic ties with Japan and banned the entry of Japanese immigrants. The Japanese Brazilians had their properties seized, and were prohibited from relocating, taking part in meetings, or traveling without government authorization. They were also prohibited from publishing newspapers and from having their own radio shows, and even their right to speak in their mother tongue was eventually abolished. Letters no longer reached Japanese Brazilians. In other words, information about Japan had been completely interdicted.

The Japanese in Brazil had a community spirit, partly resulting from the difficulties of having to adapt in various ways to a very different country. They strived to gather together through associations and organizations of a social, cultural, charitable, or even political nature, without ever losing their nationalist spirit of love for their homeland, which was always very strong among them.

Shindo Renmei emerges

It was in this context that emerged Junji Kikawa, a 67-year-old former Japanese Imperial Army colonel who lived in the Upper Paulista region [railroad-centered stretch in northwestern São Paulo State]. In August 1942, as a consequence of a violent confrontation between Brazilians and Japanese nationals in the town of Marília, São Paulo, he founded an organization named SHINDO RENMEI (in Japanese, “The League of the Subjects' Path”), a nationalist group aiming to unify the Japanese colony around the Yamato Damashii, the Japanese warrior spirit.

The organization began by handing out leaflets that filled their compatriots with the hope of victory while encouraging their belief in the eventual success of their side in the war. Supporting even acts of terrorism and sabotage, the leaflets recommended discontinuing the production of silk and mint, then in the hands of Japanese Brazilian producers, warning that such activities helped the U.S. in the manufacture of parachutes (silk) and nitroglycerin (mint/menthol).

But it was only after Japan surrendered on Aug. 13, 1945, that SHINDO REINMEI showed its true terrorist and bloodthirsty face.

With the end of the war, many Shindo Renmei members refused to believe the official reports about Japan's defeat. From then on, their objectives would focus on punishing “defeatists,” disseminating the “truth” that Japan had won the war, and defending the emperor's honor.

In the eyes of the organization, the Japanese Brazilian community was divided into two groups:

The kachigumi, or “the victors” – those who believed either that the war was still raging or that Japan had won. They represented the majority of the community's poorest members, who still intended to return to Japan.

The makegumi, or “the defeated/defeatists,” derogatorily called “dirty hearts” – those who believed the news of Japan's defeat. They were generally the better-educated and better-positioned members of the community, better informed and better adapted to Brazilian society.

Firmly believing that the news of Japan's defeat and surrender were untruths, the fanatical “victors” decided that the reports were nothing more than American propaganda. Thus, through a network of Japanese newspapers and magazines, they began spreading “the truth” that Japan was the great victor.

They created a blacklist with the names of the makegumi, who were condemned to die for having committed high treason against the emperor.

The death sentence espoused by the organization was preceded by a letter sent to the makegumi chosen to die, recommending the seppuku (compulsory suicide) because they would then be able to “recover their lost honor.” That we know of, no makegumi selected to die went along with the macabre suggestion. Those who turned it down were executed with firearms; in some other cases, katana swords were used.

Shindo Renmei's executioners, the tokkotai, were mostly young members who justified their deranged behavior as a form of “strict adherence to duty.” For that reason, they didn't feel any guilt.

The attacks

The tokkotai's first victim was Ikuta Mizobe, managing director of the Agricultural Cooperative of Bastos, situated 285 miles northwest of the city of São Paulo. On Aug. 15, 1945, the same day Emperor Hirohito signed the surrender document, Mizobe issued a statement to his employees confirming that Japan had been defeated, doing so in a firm but sad, desolate, highly personal manner. After all, his heart was never “dirty,” he always saw himself as Japanese, having never turned his back on his origins. By signing that document, Mizobe had no idea that he was also signing his death warrant. At dawn on March 7, 1946, he was cowardly murdered at his home, shot in the back as he left the bathroom, located outside the house. He left behind a widow and six children – two had already died while the three youngest ones were still underage.

In the days that followed, there were attacks against the industrialist Nomura and the former diplomat Furuya, both in the state capital and for the same reason – that is, treason against the fatherland.

In the 13 months that followed, from January 1946 to February 1947, Shindo Renmei took the lives of 23 people and wounded 147 others, all Japanese Brazilians. During this period, São Paulo police arrested more than 30,000 Japanese immigrants, with approximately 400 members sentenced to varying prison terms. Their leaders and assassins received deportation orders, though these were never enforced. At least, by that time everyone was fully aware that Japan had been defeated in World War II.

Poorly healed wounds

Decades have passed. Even so, many members of the Japanese Brazilian community, especially the older ones, who lived through or learned about that somber affair, don't feel comfortable broaching the subject. Some would rather bury it once and for all.

One can debate the moral and sociological aspects of those events within the context of that troubled period and in light of the nationalist Japanese character, but one cannot forget the wounds that the attacks left on the family members, who, following the assassinations, became orphans overnight, losing their main provider.

That was the case of Mrs. Aiko, Mr. Mizobe's daughter; at the time of the incident, she was a recently married new mother. Currently about to turn 98, Mrs. Aiko has lived her life holding a grudge inside her and a hatred for the self-confessed murderer. She felt at peace only when, unexpectedly, about seven years ago, she was sought out by the executioner's daughter and granddaughter, who humbly came to beg forgiveness for the atrocity committed by their father/grandfather. They only learned about it after becoming adults and confessed that they, too, were able to find peace of mind only after having finally managed to locate Mrs. Aiko and ask her for forgiveness on behalf of their family.

* The author of this text is the grandson of Mr. Ikuta Mizobe and the first-born of Mrs. Aiko Higuchi.

© 2018 Katsuo Higuchi