As this past September 2018 marked the 30th anniversary of the Redress settlement, I want to share some learning about one of the most important Japanese American heroes, Dr. Gordon Kiyoshi Hirabayashi (1918-2012), whose stand against the 1942 curfew and internment of JAs during World War Two continues to inspire new generations.

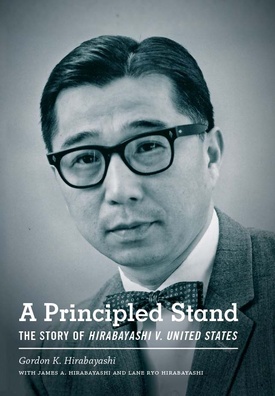

A Principled Stand: The Story of Hirabayashi V. United States was created by his late brother, James (1926-2012), who was a professor emeritus of Asian American History at San Francisco University and nephew Dr. Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, retired professor of Asian American Studies and the George and Sakaye Aratani Professor of the Japanese Incarceration, Redress and Community at the University of California at Los Angeles. Using Gordon’s own prison diaries and wartime correspondences, they weaved together the remarkable story of Gordon’s unrelenting resistance to the injustices that were perpetrated by the Roosevelt government. He protested on the grounds that those decisions were in contravention of the U.S. Constitution.

While Gordon never did write his autobiography, this story goes some way to tell it in some detail, focusing primarily on the war years.

Gordon’s father left Japan in 1907 and settled in Seattle where he founded a Mukyokai fellowship group and a Hotoka Club. Mukyokai is a non-church Christian movement in Japan founded by Uchimura Kanzo.

Four families, including two Hirabayashi families, settled in Thomas, Washington, a rural community 30 kilometers south of Seattle, where they formed the White River Garden Corporation, a co-op farm. They eventually lost the land to the state as it determined that the land was purchased by ‘deceit and a subterfuge’ (the parents used their Nisei child’s name to purchase it as the 1923 Alien Land Law prevented non-citizens from owning land and before 1952 immigrant Issei were ineligible for naturalization).

The Katsunos and Hirabayashis fought the state courts on this issue, losing at each stage and eventually had to lease their own land in order to continue farming there. As a child Gordon was brought up in an environment that encouraged discussion, cooperation and that reinforced the belief that one should stand up for their beliefs.

Hirabayashi grew up very much like any other American kid: he was a Boy Scout and active member of the Auburn Christian Fellowship (ACF), an interdenominational group formed by Issei. While at Auburn High School, he was also a member of the YMCA and was inspired by the slogan: “To create, maintain, and extend throughout the school and community high standards of Christian character.” Though he took to heart the values that he was taught in school too, he understood the double standard that made JAs and others second class citizens.

So, rather than celebrate his Japanese ethnicity as is encouraged in schools these days, he saw his “Japaneseness” as a barrier to being accepted as a full-fledged American: “I wanted to escape the disadvantage by shunning Japanese language and many of the cultural patterns that were visibly ‘exotic’ or peculiar’. I feel my experiences are very common to the Nisei as a whole. So, I began to tell myself that first class citizenship was a viable objective. I chose this to be the reality that I could live for.”

Recalling one civics class, Gordon mused: “I was exposed to American ideals to which I subscribed wholeheartedly - ideals such as all persons are created equal, with liberty and justice for all, equal opportunities under the law, and citizenship regardless of race, religion, creed, or national origins. Before World War Two, human rights laws were nonexistent.” While a somewhat idealistic picture of a young Hirabayashi is presented, it was in fact those qualities and belief in an America that had not evolved to include Japanese Americans yet, that made Hirabayashi such an endearing, modest and proud American hero.

Gordon initially enrolled as an economics major at the University of Washington where he was a member of the Japanese Students Club as well as the YMCA. At his YMCA dormitory, he was in contact with international students, including some Canadians, Chinese, a couple of Jews. There were no blacks and he was the only Nisei.

A trip to New York City as a member of a YMCA leadership group was particularly eye opening: “In Seattle I always considered, as second nature, whether I would be turned back at the door for racial reasons. In New York, I didn’t have to think about being Japanese or whether I would be embarrassed or kicked out at the door.” In November 1941, he and good friend Howard Scott, both became Quakers.

On February 19, 1942, U.S. president Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which delegated broad powers to the secretary of war and his military commanders for the purpose of protecting national security. This order gave them the power to remove any perceived threat from military areas. Gordon dropped out of UW in March 1942 then volunteered for the fledgling American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) that sought to assist the Japanese Americans whose lives were being destroyed.

Even after his mother pleaded with him to put his principles aside, Gordon responded: “If I change my mind because of your pressure, it wouldn’t be good. I need to retain my own self-respect, because when I take a stand, I am following what I think is right. I can’t change my views, since I’d rather remain true to my beliefs and be true to you as your son.”

Hirabayashi refused to comply with the government orders to join his family in a concentration camp because he saw this as being against the principles of the US Constitution. He was fully prepared to accept the consequences of his actions and did so.

Explaining his position, he said: “They’re wrong! My position was a positive one, that of being a conscientious citizen. It was this desire that prevented my participation in the military as a way of achieving peace and democracy and other ideals for which we stand. How could you achieve nonviolence violently and succeed? War never succeeded before.”

Civilian Order No. 57 commanded all Japanese and Japanese Americans “out of their homes and into special, totally segregated, camps.” The Hirabayashi family was first imprisoned at the Pinedale Assembly Center located close to Fresno, California, before being transferred to the Tule Lake Concentration Camp in Northern California.

Gordon was first jailed at King County Jail in Seattle for breaking the curfew order that was issued on March 24th, 1942 by General John L. DeWitt. Hirabayashi decided to defy the government’s order and presented himself to the Seattle FBI office on May 13, 1942, submitting his reasons for doing so in a statement entitled: “Why I Refuse to Register for Evacuation.”

He wrote, in part: “If I were to register and cooperate under these circumstances, I would be giving helpless consent to the denial of practically all of the things which give me incentive to live. I must maintain my Christian principles. I consider it my duty to maintain the democratic standards for which this nation lives. Therefore, I must refuse this order for evacuation.”

After he was released on bail, he volunteered to help Japanese Americans who had resettled in the Spokane, Washington area that was outside of the Western Defense Command’s military zones. When the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Gordon’s conviction on the charge of violating the curfew order, he hitchhiked down to Arizona on his own initiative where he served additional time in a work camp where prisoners were building a highway through the mountains.

In 1944, he was tried and convicted a second time for his refusal to fill out the government’s so-called loyalty questionnaire (Question #27 asked if Nisei men were willing to serve on combat duty wherever ordered and asked everyone else if they would be willing to serve in other ways, such as serving in the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. Question #28 asked if individuals would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor of Japan) and sent to McNeil Island Penitentiary in Puget Sound, not far from Tacoma.

After the war, he pursued his studies and earned a PhD in Sociology from the University of British Columbia in 1951. He taught overseas in Egypt and Lebanon then spent the remainder of his career as a professor of sociology at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada.

Vindication: Coram Nobis

In the early 1980s, an original draft of manuscript written by General John L. DeWitt “Final Report: Japanese Evacuation From the West Coast, 1942”, was discovered in 1982 by researcher/activist Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga (1924-2018). This was critically important as there was a significant difference between the draft version that stated that it “was not because of insufficient time” but, rather, that “Japanese cultural traits” made it impossible to separate the “sheep from the goats”, to distinguish who could be trusted, and the final government version that contradicted this saying that it was because of lack of time due to the wartime emergency that made ‘mass exclusion’ the only alternative. Racism was a clear factor. It was believed that all of the original drafts had been destroyed.

As serendipity would have it, University of California political science professor, Peter Irons, working alongside Herzig-Yoshinaga discovered correspondence from Edward Ennis, a Justice Department lawyer, who prepared the Supreme Court brief to Solicitor General Charles Fahy regarding the naval intelligence report that also contradicted the army’s false claim of ‘wide spread disloyalty among Japanese Americans.’ His report advocated individual loyalty hearings. Fahy ignored the warning not to withhold these findings on the racial bias of mass incarceration from the Supreme Court, which allowed lawyers in the 1980s to invoke the rarely used writ of error coram nobis.

The Civil Liberties Act which granted reparations to Japanese Americans was passed on August 10th, 1988. The following month, on September 24th the U.S. Supreme Court found in his favour that, “A United States citizen who is convicted of a crime on account of race is lastingly aggrieved.” It is also noteworthy that Hirabayashi was awarded the U.S. Congressional Medal of Honour in 2012 by President Barack Obama.

“Why did I cling to the constitutional values in spite of the wartime injustices? It wasn’t the Constitution that failed me. It was those entrusted to uphold it who failed me.”

A Principled Stand: The Story of Hirabayashi V. United States

By Gordon K. Hirabayashi with James A. Hirabayashi and Lane Ryo Hirabayashi

(University of Washington Press, 2014, 216 pp., $19.95, paperback)

© 2018 Norm Ibuki