What does being Nikkei mean to you today?

Being Nikkei today means being aware of who I am regarding my personal history, and being aware of what continues to inspire me as a writer.

Is this something that you are passing on to your kids? If so, how and why? What is their reaction to these stories and their connection to Japan?

Am I passing this on to my kids? I have tried my best to expose my children to life in Japan, for example, and by having them take Japanese language classes, but ultimately, as adults, it is up to them to decide how important their cultural heritage is to them and whether they want to maintain aspects of it. My husband is of Russian Mennonite background, and we are also Anglicans; there are lots there, too, for my children to draw from as inspiration for their spiritual and cultural lives.

How has the writing of TEOs affected your relationship with your own family here and in Japan? What about the JC community as a whole?

We will see, now that the book is out! The writing of this book required a lot of their assistance—on my mother’s side, it required the help of translators - my mother, my aunt, and my cousin were all involved in that. Also, on my father’s side, my cousins and my uncles helped me on my quest to find out what happened to Saichi’s land in Japan. So in some ways, TEO has been a bit of a family endeavor. It’s too early to say what the JC community will think of this book, but I will certainly be interested to find out!

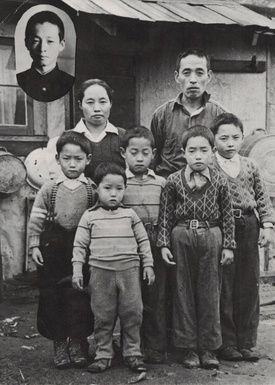

Many of your memories of family, e.g. Auntie Kay are particularly poignant. What do we risk if we lose these precious family images and stories? What ones were you told about the experiences of the Itos in Surrey and your mom?

If we lose these precious family images and stories, we lose them. Aunty Kay died a few years ago; it would have been great if I could have presented her with this book when she was alive, but she was alive, at least, when I discovered what had happened to her father’s land in Japan in 2007. Her death precipitated the need for me to actually write down the stories, and then that became part of the telling of TEO.

Offhand, I can’t think of many other works by Nikkei writers that address our post-WW2 experience in the way you have. Did you have any particular goals that you wanted to achieve in the writing of this memoir?

There is Joy’s (Kogawa) memoir, Gently to Nagasaki. Mostly this book is for posterity; what I did learn though in writing the book was that it was also more about me than I had thought initially. It was about me as a writer on a quest to find out who I was.

There seems to be a lot here that speaks to the post-WW2 Canadian Nikkei experience, e.g. loss of land and community that the Americans didn’t experience.

I experienced the internment through my imagination, and that is for me as real as it can get, as an artist. In TEO, I talk about the passage in the book of John in the Bible - In the beginning was the Word… Well, we do not all experience things directly and perhaps it is questionable to say if we have even experienced things at all without something like words mediating the event to our consciousness.

As someone who didn’t experience the internment directly, what is the significance of it for a Sansei like you today?

When I write about the internment, I relive the past of my Issei and Nisei family members, and that reliving is its significance to me as a Sansei.

Were there some things that you didn’t/couldn’t include?

Yes, many. My mother is Japanese. She survived the wartime bombing raids of Osaka and was evacuated to the mountains as a twelve-year-old girl. Her experiences, I feel, constitute a whole other book of its own.

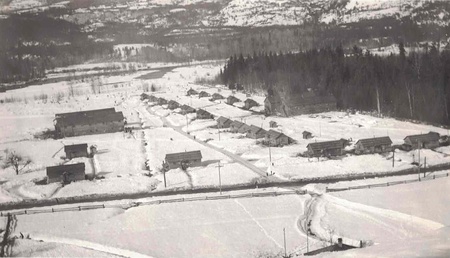

I loved the road trip section. How did this inform you about the experience of internment?

Thanks for saying so. I felt the road trip was a natural way to get into the past, and the part of my aunt in my dream is true. I did have a dream about her, and because I’m very sensitive to dream imagery and its interpretation—it’s the poet in me—I felt she was leading me into a way of telling her story that would be structurally appropriate.

That road trip was my first encounter with my family’s internment past. But I was only 12 years old then, so much of its significance was lost on me at the time. However, when I encountered my grandfather’s account of the trip in his travel diary of that year, I got a new perspective in words on that experience that helped me interpret events better.

Whatever became of the Ito property in Surrey? Any lingering feelings?

Well, the whole area is subdivided now into residential lots, so I don’t know where the Ito property is anymore. I do feel some connection with St. Helen’s Anglican church there though; it’s a beautiful church building, still standing from the time when my family was living there, and it’s a beacon to me of how some things can even last, still persist with meaning in the lives of people today.

Through the process of writing and researching your family history, how forthcoming was your own family with sharing their stories? Who were the key helpers?

My family was very forthcoming. On my mother’s side, I mention all the translators that helped translate my grandfather’s memoir for me - my Aunt Michiko, in particular, her daughter, Michino, and my mother, too. Also, on my father’s side, as I said earlier, there were my cousins and uncles who helped, in particular, to find out what had happened to Saichi’s land in Japan. Because I was doing this book, they told me stories that perhaps they had never told anyone before. Working on this book gifted me with their stories.

What kept you going through this long process? Is there a sense of release?

Persistence, tenacity, doggedness. So yes, I do feel a release, but also a bit of sadness, too.

What do you hope is the lasting value of this book?

Posterity. It’s a record. My grandfather wrote his memoir saying it was for his grandson who was asking questions about his life. Little would my grandfather know, that he was writing it also for me, strangely enough! So, the lasting value of this book is for whoever reads it and enjoys the story.

Any advice to anybody who might be thinking about doing something similar about their family history?

Just write. Don’t put it off.

Any particular Japanese or Nikkei writers who you are indebted to?

Joy Kogawa, of course. Also, Misuzu Kaneko, of course, the Japanese children’s poet I’ve been translating with my aunt Michiko. David Fujino, was a wonderfully quirky poet, I quote in my book. Roy Kiyooka’s mothertalk was an influence, as well.

What is your connection to Japan today?

I continue to do translations of Misuzu Kaneko’s poetry with my aunt and want to continue doing that as a way to promote her and Japan to the literary world.

How do you hope that this story will add to the greater Canadian Nikkei narrative?

My father’s story is one of the ‘repatriates’ and has not been written about a lot even though what happened to JCs in this regard is so different than to what happened to JAs. So, I hope my book will contribute to the Canadian Nikkei narrative insofar as it looks at the impact that repatriation policy had on future Japanese Canadians of my generation and later, who, I feel have stronger ties to their Japanese culture than to those who stayed in Canada and were shamed into being invisible about their identities.

Do you see an ongoing evolution of Nikkeiness? How do you see this changing for your kids’ generation?

Yes. Japan is very hip so it’s appeal to young people is great. If a younger person’s interest in Japanese culture can be cultivated in such a way that it can be tied into a sense of their identity, then all the better.

Do you have any final thoughts that you would like to share with readers?

No, other than read my book!

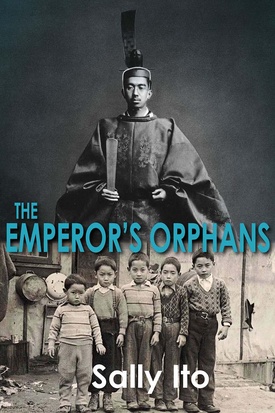

The Emperor’s Orphans

By Sally Ito

(Winnipeg: Turnstone Press, 2018, 207 pages, $21 (CDN), ISBN 978-0-88801-567-9)

Available online from Amazon and Chapters Indigo

© 2018 Norm Ibuki