“I could draw what I think your feelings might be about Richard’s story,” my daughter suggested. Richard Murakami was sharing his story about his concentration camp experiences as part of the intergenerational group discussion at the recent Tule Lake Pilgrimage last June. It was my seventh pilgrimage, but my children’s first. My 8-year-old daughter, Akina, was getting antsy. Like many children, she typically needed much more time to feel comfortable talking in front of adults she does not know. Akina might appear uninterested in what they had to say or standoffish. But I knew she was listening on some level. She started fidgeting more as the session went on. So using my experience as a clinical psychologist working with children, I suggested that she draw an image while listening to Richard’s story.

Akina’s fidgeting did not have to do with Richard. He told very compelling stories of being ten years old at Tule Lake. He was informative and animated. Richard clearly expressed his feelings, using words like “I was scared” and “all that pent-up anger” as he talked about readjusting to life after incarceration and moving into a predominantly White high school. Doing so enabled my children to relate to his experiences. I suspected that Akina struggled in part because of the emotions it evoked.

Setting a stage for enabling a connection between a former inmate and a young child is not easy. Former inmates are at the stage in their lives where they review their past. This process can be fraught when it entails the traumatic stress of camp. It can become all the more meaningful then when a compassionate listener bears witness to their story. Much has been said about this in the Jewish community of Holocaust survivors, but perhaps not as much in our own community. Children who listen and reflect a former inmate’s story can potentially play an invaluable role. They breathe hope for aging former inmates that the next generation can carry their stories and its lessons forward.

What is tricky about bridging a connection is considering young children’s needs. Most young children process their feelings quite differently from adults. Words don’t come so easily. Instead, they use play, art, imaginative stories, and other indirect ways to express themselves. Akina loved drawing. So she took to the pen and paper I brought and began drawing my feelings about Richard’s story. I say “my” because she seemed to need that extra distance from her own experience.

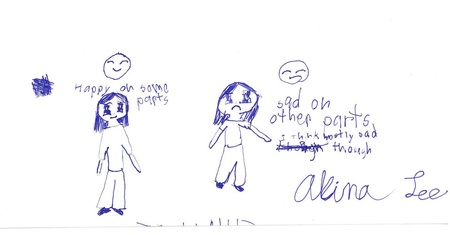

So while our group broke up into smaller groups to talk about what Richard’s story evoked in us, my daughter drew a picture of two women. For the one who was smiling, she wrote, “Happy in some parts;” and for the one who was frowning, she wrote, “Sad on other parts. But I think it was mostly sad though.”

When we returned to the larger group, Akina let me show Richard her drawing. Richard was touched. He asked whether she could sign the drawing and give it to him, which she did. Akina again looked askew and kept drawing for the remainder of the session, producing a compelling series of drawings – drawings of images that she would not typically do at home or in school. The images were evocative. Later in the evening, I sat down with her and inquired more about her drawings. “What happened? What were they feeling?” I asked.

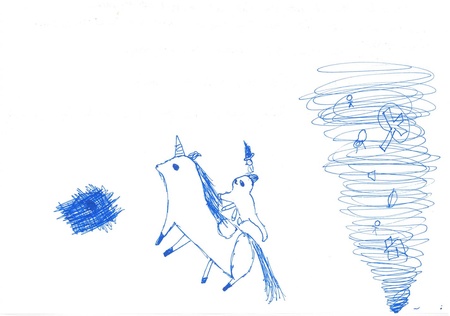

In Akina’s second drawing, enormous, rodent-like beasts with unicorn horns and wings are “trying to make sky with their unicorn horns. They’re feeling happy because they’re the only ones who have powers.” She is contrasting the magical powers of these fantastic beasts with the vulnerability of the tiny village below.

In the next piece, Akina drew a tornado, where people, a chair, a house, and a tree are uprooted in its maelstrom. In this image, she is reflecting the turmoil that Richard and his family had experienced in being forced to move so much before, during, and after camp. Akina elaborates, “The tornado knocks down everything. The people in there (tornado) are sad because they got in the tornado.” A unicorn is carrying a number of small animals away from the tornado. Akina shared how the animals “just got saved from the unicorn because of the tornado. And the animals are feeling grateful because they didn’t get hit by the tornado.” Akina is expressing her feelings of gratitude for not having to experience the hardships of incarceration and dislocation that Richard had to go through as a child. Please read Richard’s article about his reaction upon seeing her drawings and narration.

Akina then drew a gigantic, beautiful flower surrounded by a small group of people. “Everyone’s looking at the flower because it’s so giant. And the others are crowding around to watch because they never seen such a giant flower,” she said. When I asked her what made the flower so giant, Akina stated, “Because the person watered it a lot and took care of it a lot. The person is feeling happy cause it was his flower, and it was special.” Akina is depicting our intergenerational group coming together, listening, and admiring Richard’s story, a story that had themes of resilience.The grand flower is a symbol of his special life story, in which he had taken good care to water and grow.

As our intergenerational session came to an end and people started exiting the room, Akina stayed behind, intently working on her final drawing. In this drawing, a clutch of eggs with a baby chick is hatching, and pecking on the egg next to it, while a proud mother looks on. Akina describes how the baby chick is “trying to peck on the egg to help it hatch.” She goes on to say how both the mother and chick are “happy” in anticipation of more siblings. Our intergenerational group emphasized the need for the next generation to be the keepers of Richard’s story and our history. Akina seems to highlight how the next generation helps one another to bring hope for future generations.

Richard shared that he was honored by Akina’s drawings. He said, “Her interpretation of what was said during the Intergeneration Group through art highlighted her mature thinking, way beyond an eight year old.” Richard was especially impressed and pleased with Akina’s interpretation of the “need for the next generation…” to keep our story alive. He reflected, “At my age, I keep wondering who is going keep our story and history alive. Takumi [Lisa’s 11-year-old son] and Akina are our future. I feel very comfortable that they will become leaders of our community.”

Akina expressed the depth of her experience in the Tule Lake Pilgrimage’s intergenerational group through her art. Japanese American families and other community programs can foster similar connections across generations. Children can use art, collages, and other indirect ways to process their feelings associated with our history of incarceration. Adding their words to their work illuminates their experience and how they relate to former inmates.

Nowadays, the majority of former inmates were children in camp. Their stories reveal a unique and complex vantage point of incarceration. Richard highlights this in his article. Seeing my daughter pick up on so much of her surroundings made me appreciate how much a child in camp might have struggled with, whether consciously or unconsciously. Especially for those who were young, like my daughter, they might not have had the words to articulate their feelings and experiences. The same linkages can be made to that of Latino children who were traumatically separated from their parents at the border due to President Trump’s immigration policy.

As a Japanese American parent, I wrestled with how much to shield my children from the trauma of incarceration and how much to expose them to it to understand their history and use that lens to inform them of current day issues. I knew that my 11-year-old son would be ready, but I was not so sure about Akina, being younger. This is a similar process that many other communities face such as African American, Native American, and Jewish families. Akina insisted on coming to the pilgrimage, however. She did not want to miss out on the opportunity. One cannot underestimate the power children have to shed light on our collective experiences so long as we give them a means to show it.

© 2018 Lisa Nakamura