A symbol of Seattle's minority culture

The International District is located south of downtown Seattle. Japantown remains in one corner of the district. At its peak before the war, around 8,500 Japanese immigrants lived and ran businesses there. However, after the start of the Pacific War, a presidential decree led to all Japanese residents being repatriated to internment camps. Following on from our previous article, which introduced Japantown before the war , here we trace the changes in Japantown from wartime to the postwar period, and up to the present day.

Internment of Japanese Americans and the Japanese Town that Remained

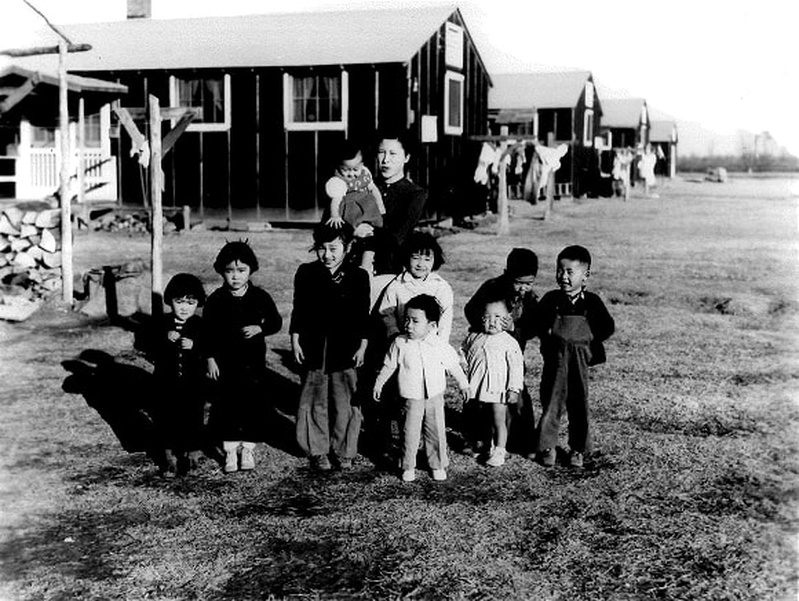

In December 2015, at a meeting of naturalized immigrants in Washington DC, former President Obama said, "The incarceration of Japanese immigrants in internment camps is one of the darkest moments in America's history." In the same month 75 years ago, former President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which resulted in more than 120,000 Japanese people, including American citizens, being deemed "enemy aliens" and deported to internment camps. Many of the residents of Seattle Japantown were sent to the Minidoka Internment Camp in southern Idaho. They were forced to leave behind everything they had built up, including their businesses, land, property, furniture, and mementos, except for the bare minimum that could fit in a suitcase. Within a few days, Seattle's Japantown was completely emptied.

Meanwhile, Seattle continued to grow during the war. The Boeing Company, which was founded in Seattle in 1916, grew rapidly due to demand for military aircraft. The population of Seattle increased from approximately 370,000 to approximately 470,000 between 1940 and 1950, and the majority of this population increase was due to African-Americans employed as workers at the Boeing factory. In 1940, the African-American population of Seattle was approximately 3,800, about half the number of Japanese-Americans, but by 1950 it had rapidly increased to approximately 157,000.

To accommodate African-American workers, the city of Seattle built the public housing complex "Yesler Terrace" in 1941. It was built on the east side of Japantown, where many Japanese-Americans lived. Naturally, documents state that there was a lot of friction between the Japanese-Americans who returned to Japantown after the war and the African-American residents who had taken over their homes and stores during the war.

Civil Rights Movement, I-5, Kingdome

Jackson Street, which was lined with Japanese stores before the war, began to be lined with jazz clubs in the 1950s. Japanese families who had once returned to Japantown began to move to the suburbs, and Japanese residents and Japanese stores gradually disappeared from Japantown. When US-China relations improved during World War II and the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, Chinese immigrants increased again, and "Chinatown," centered around King Street, became thriving. In 1951, the mayor of Seattle at the time began using the word "international," and the "International District" came to be recognized as a place where Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, and African residents, in other words, non-white residents, could gather.

In the 1960s, the civil rights movement, centered on African-American residents, became active in Seattle. Many young second-generation Japanese-Americans also began to identify as "Asian-Americans" and appealed for the elimination of discrimination. In the early 1960s, the construction of I-5, which divided the International District in half, and the construction of the Kingdome, which was carried out from the late 1960s to the early 1970s, led to violent protests by young Asian-Americans, known as the "Kingdom Protests." In fact, the construction of I-5 resulted in the demolition of many of the buildings and houses that had existed in Japantown before the war. It is said that many Japanese-American residents were forced to leave Japantown due to eviction caused by this construction.

Communicating the history and culture of Asian minorities

After the Korean War and the Vietnam War, Korean and Vietnamese stores began to appear in the International District in the 1970s. In particular, after the area was divided by I-5, a row of Vietnamese stores began to appear in the eastern area, and an area called "Little Saigon" was created.

Currently, the International District is home to many nonprofit organizations working to preserve and pass on the history and culture of Asian immigrants, including Japanese immigrants, such as the InterIm Community Development Organization (InterIm), which was founded in the wake of the civil rights movement and the Kingdome Protests, and the International District Historic Preservation and Development Agency (SCIDpda).

In 2016, InterIm opened Hirabayashi Place, a complex on Main Street that includes low-income housing and a daycare center. The building is named after Gordon Hirabayashi, who resisted the internment of Japanese Americans during the war.

In addition to managing and operating historical buildings, SCIDpda also supports the Friends of Japantown, an organization that brings together businesses in Japantown to improve infrastructure and plan events. Friends of Japantown held a summer festival in Japantown on August 26, 2017. Over time, the importance of conveying the history of Japantown has begun to be recognized anew in Seattle, a city with a strong liberal orientation that values diversity.

References

Taylor, Quintard. The forging of a black community: Seattle's Central District, from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era . (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994)

Chin, Doug. Seattle's International District: The making of a Pan-AsianAmerican community. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002)

Seattle: International Examiner Press

A chronology of the history of Japantown (wartime and postwar)

| 1940s | 1941 | Attack on Pearl Harbor, start of the Pacific War Seattle's first public housing complex, Yesler Terrace, is built. |

| 1942 | The Japanese American Internment Order (Special Executive Order No. 9066) is issued. | |

| 1945 | End of the Pacific War | |

| 1950s | 1950 | Start of the Korean War (until 1953) |

| 1951 | The Treaty of San Francisco between the United States and Japan is signed. | |

| 1960s | 1962 | Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech |

| 1964 | Wing Luke becomes the first Asian-American to serve on the Seattle City Council. Civil Rights Act is enacted. The Gulf of Tonkin incident leads to the Vietnam War (until 1975). | |

| 1965 | Highway I-5 completed | |

| 1968 | Kingdome construction decided by local referendum | |

| 1969 | InterIm founded | |

| 1970s | 1972 | First Korean business opens at ID |

| 1975 | Fall of Saigon, Unification of Vietnam SCIDpda was founded | |

| 1976 | Kingdome completed. President Ford rescinds Executive Order 9066. | |

| 1978 | ||

| 1980s | 1988 | President Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (Japanese American Reparations Act). |

| 1990s | 1994 | The City of Seattle formulates its Urban Village Strategy, and revitalization of downtown areas, including the ID, begins. |

| 1999 | Sefco Field completed | |

| 2000s | 2000 | Union Station was restored and an office complex was built on the site. Uwajimaya Village was built. Uwajimaya moved to its current location. Kingdome was demolished. |

| 2002 | Century Link Field completed | |

| 2003 | Kobo at Higo opens at the former Higo Variety Store site | |

| 2010s | 2016 | Hirabayashi Place completed |

*This article is reprinted from Seattle lifestyle information magazine Soy Source (June 9, 2017).

© 2017 Soy Source / Misa Murohashi, Megumi Matsuzaki, and Mao Osumi