DN: Now that you’re a parent, are the conversations about identity you may have had with your kids similar or different than those you may have had with your own parents? Or a little of both?

KF: Ha! That assumes I ever had a single conversation about identity with my parents! I remember after I did Banana Split (my first film of note) and showed my parents. We watched it together, and afterwards both of them made a point to tell me they had no idea I had struggled as a kid, or got beat up, or had trouble navigating the dating and race arena with girls. And they’re telling me this when I’m 25 years old and in graduate school! My dad said he always thought I had the best of both worlds, the world at my feet. While my mom apologized to me because she thought it was somehow her fault I got beaten up because it was her genes that made me brown. And I had to tell them all children deal with stuff like this.

Sure, for some it’s not about race but it’s about something. It’s about no money or no home or a dad in jail. It’s about being ESL or not being Asian enough or being overweight or skinny or not being “smart” enough or who you’re attracted to. But I also told them I wouldn’t change my childhood for anything. I like who I am. I like what I’m able to make now. And everything I went through, every experience, every interaction – good and bad – got me here to this place. I explained it as best as I could, but I don’t know if my parents fully understood. Years later, as my work got more recognized and well-known, they seemed to get a lot more comfortable with it. I think they were always proud of me. But at some point that went from being proud to being proud and comfortable. Maybe because I wasn’t starving.

My son, Jack, is nine years old. He asks me about girls. It’s pretty adorable ... he reminds me so much of me as a kid. He asks me if it’s normal to like girls so much and why bullies bully and why people litter. He asks me how you get a girl to like you and I tell him, “Son, men have been asking that question for thousands of years.”

Meanwhile, my daughter, Pepper, doesn’t even like men (which is just fine with me). She’s five. She wants to know about My Little Pony and Star Trek and scorpions and how whales communicate. These are the things we talk about.

I never talk to either of them about race. Jack kind of knows what Hapa means, but not really. He hangs out with his Chinese family and his Filipino cousins and lives in super-White Santa Barbara and wonders why dad talks differently when we’re in Hawai’i. But he doesn’t give race much thought. He’s more interested in Legos. I didn’t have the option of not giving it much thought as a kid, so I’m glad he can ignore it. For now at least.

DN: You were born at a time when interracial marriages were still illegal. What do you know now that you’d wished you’d known back during your childhood? Or if you could travel back in time to talk with your younger self, what would you say to him?

KF: Good question. It’s basically what spurned The Hapa Project — to make the book a seven-year-old me could look at and realize it wasn’t just him in the world. I wish I knew back then that it would all be okay in the end, that the very things I disliked about myself would morph into the very catalysts fueling my artwork, that I would need them. I wish I knew that as an adult I’d be proud of my heritage, proud of my family. I’d introduce seven-year-old me to API creators and role models that were doing cool things, not just being the butt of mainstream jokes. I’d show him API men that were successful, handsome, and desired. I’d show him the beauty of API women, and plant the seeds for teenage understanding that any preferences he had against dating them were just projections of his own self-judgement. And I’d tell him no one really cares if you can’t hit a softball. And that whether it’s being athletic, developing confidence, taking a risk in your artwork or telling a girl you like her, it really all comes down to just deciding to do something and fully committing. Making that decision and going for it.

And I’d tell him to draw more without apology, to make more art, and to quit those stupid piano lessons no matter how much your mom keeps yelling at you. Go out today and get a damn electric guitar already!

DN: What have been some of the most interesting or unexpected comments or reactions that you have received from people regarding your work? In particular, any interesting reactions to the current show?

Every comment, every reaction is different. Even if two viewers are saying the exact same words, it’s still a different experience. I’m at the point with my work that I don’t solicit feedback, but I’m appreciative when someone wants to share their experience with me. I’ve been living with the project, being partners with it, for the better part of two decades. I’ve lost my ability to see it with fresh eyes. So I’m grateful to get to hear from people who aren't trying to be smart, or to impress someone, but who are just speaking from the gut.

DN: What are you working on next?

KF: I doubt many people understand how much these shows take out of me — physically, emotionally, even spiritually. Perseverance was working every single day for two years, from wake until sleep ... conceptualizing the overall design and layout, figuring out how to fabricate metal, wood, fabric in ways I’d never done before, supervising 15-20 assistants, putting daily fires out, and making it all happen without any kind of template whatsoever. With my friend Taki handling the curatorial duties, every part of that physical show — from the layout and design to the way each kite’s angle hung from the ceiling to the precise amount of smoke I’d burn into each hanging piece of aluminum — every part of that was mine. And it's the greatest exhibition I’ve ever created. I gave everything to it. Then I’d be walking in the show and hear some visitor say, “It’s cool how the museum decided to hang kites from the ceiling.”

I know good design is invisible, but those comments were still death by a thousand cuts. It’s like a properly done dinner party. You need the right time, the right season, the right mix of guests. You consider style of invitation, interior design, seating, decor, conversation topics, music, temperature, lighting — all this before you even deal with food. Same thing with creating a solo show. Everything matters. That’s the kind of overall consideration I employ when I immerse myself into the artwork.

Sure I want to show the “art” (in this case, the photographs), but in reality, the whole show is an artwork as well as an experience. Everything matters. The fact that the koi were hand-painted over weeks by volunteers matters. That I drew them by hand matters. That I strung the DNA helix with a torn shoulder matters. You don’t simply see that type of commitment, but I believe in some ways you sense it when you enter a show. If it’s created right, it just feels done.

After I finished Perseverance, I gave myself a year off to recover. A year off to be a dad, to swim again, to get my heart broken, to breathe. A year passed and I wasn’t even close to being able to make work again. So I gave myself another year. I gave myself permission to rest, to heal, to mess around.

And after two years of not making art, I finally recovered and began getting hungry again. And that was the beginning of hapa.me. I spent the next two years cycling up again – making the exhibition, working on it every day, dreaming about it every night. And as soon as the show opened I immediately began getting the what-are-you-working-on-now question. My answer? “Nothing.”

DN: Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

I’ve always considered JANM my artistic home. That may sound odd to some, that this Chinese American Hapa finds refuge in a JA institution ... and that I’ve now had more solo exhibitions here than any other artist. But it makes sense to me. Despite spending much of my childhood across the 101 in Chinatown, I’ve never felt accepted by Chinese and Chinese Americans (Chinese Hapas sure, but that’s a different story). From the beloved Karin Higa, who took a chance on me and booked my first exhibit here, to my artist mentors (and friends) Mariko Gordon, Patrick Nagatani, Bob Nakamura, Karen Ishizuka, Patrick Nagatani, Clement Hanami, John Esaki, and many others, JANM has always served as a centering institution to me as an artist. I am grateful to all the staff and volunteers, who always welcome me and my children, and who have granted me the opportunity to share my work with their audiences. It’s been an honor to be part of this community. Thank you.

* * * * *

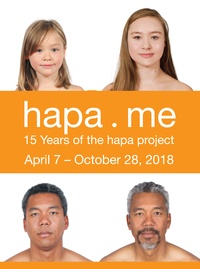

hapa.me – 15 years of the hapa project

April 7 - October 28, 2018

Japanese American National Museum

Los Angeles, California

Artist Kip Fulbeck continues his project, begun in 2001, of photographing persons who identify as “hapa”—of mixed Asian/Pacific Islander descent—as a means of promoting awareness and positive acceptance of multiracial identity. As a follow-up to kip fulbeck: part asian, 100% hapa, his groundbreaking 2006 exhibition, hapa.me pairs the photographs and statements from that exhibition with contemporary portraits of the same individuals and newly written statements, showing not only their physical changes in the ensuing years, but also changes in their perspectives and outlooks on the world.

© 2018 Darryl Mori