“We asked ourselves, how is this possible? There won’t be any Nisei at the Tokyo Olympics?”

The speaker is Luis Toyama, former president of the Nisei University Students Association of Peru (known as AUNP), an organization created in 1961 by university students whose parents were from Japan. The group organized cultural activities to promote Peruvian-Japanese relations and engaged in social work to help low-income people, among other activities.

By “we” he is referring to AUNP members and “the Tokyo Olympics” refers to the Olympic Games that were held in Tokyo in 1964.

The Nisei youth couldn’t believe that despite the Olympic Games taking place in the land of their ancestors, no Peruvian athlete of Japanese descent would be competing there.

“Who’s the most outstanding Nisei athlete?” they asked. The answer: cyclist Teófilo Toda, who had won several national championships.

“Our idea was this: The Olympics are in Japan and someone from the Japanese community in Peru should go. And for us, Toda was the symbol,” recalls Luis Toyama.

Toda had qualified to represent Peru in Tokyo in 1964, according to the Cycling Federation, but there was one problem: The Peruvian Olympic Committee said it had no resources to finance his participation in the games.

The lack of funds, however, didn’t weaken the resolve of the AUNP members to ensure that someone of Japanese origin represented Peru at Tokyo in 1964. If there wasn’t enough money, they’d have to find some.

Luis Toyama points to the efforts of Carlos Tsuboyama, then athletic secretary of the AUNP, who proposed the initiative to support Toda, convinced the association’s board to approve it, and led the fundraising campaign.

The AUNP organized a series of activities to obtain funding with support from La Unión Stadium Association, where fundraising events were held. Other supporters included the Perú Shimpo newspaper which advertised the campaign, Farr Tours travel agency which made a substantial contribution, the Cachorros Club (to which Toda belonged), and other clubs in the Japanese-Peruvian communitiy such as Unión Pacífico, Awase, Nisei Callao, and Hinode.

The campaign was successful and raised enough money to finance the cyclist’s stay in Tokyo.

PERUVIAN THROUGH AND THROUGH

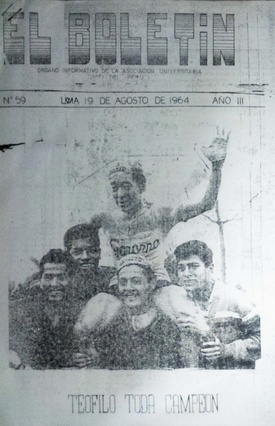

Two months before the Olympic Games in Tokyo, the AUNP published an interview with Teófilo Toda on the cover of its newsletter, highlighting his achievements. As Luis Toyama recalls, he was a symbol for the Japanese-Peruvian community.

A quick glimpse at a couple of publications from the time is enough to verify this. In 1958, the magazine El Nisei emphasized que Toda, “win or lose, always clearly demonstrated his extraordinary aptitude for fierce and valiant cycling.”

For its part, in 1960 the magazine Superación wrote: “When we talk about sports, we always have to mention Teófilo Toda. In the annals of cycling, he has written some glorious pages.”

In the interview with the AUNP, the cyclist revealed details about his life. He recalled, for example, riding a bicycle for the first time at 7 years old and said that Lázaro Shiohama, member of the Unión Pacífico club, was responsible for his becoming a competitive cyclist. “He always loaned me his racing bike,” he said.

He also publicly stated his love for another sport: soccer. He could have been a professional soccer player. “I played soccer with the Centro Iqueño youth team and later for Unión Pacífico, during the early years of La Unión Stadium.”

For the cyclist, just being able to compete in the Olympic Games, regardless of the outcome, was the achievement of one of his goals, “thanks to the initiative of the AUNP, to which I am grateful for its noble gesture toward me, and which I don’t think I deserve.”

His interviewer, Carlos Tsuboyama, who had started the campaign, had high praise for the athlete:

“The AUNP, as always, contributes material or spiritual aid to those who deserve it. And in your case, not only because you are a Nisei athlete, but because you are a model sportsman, because you are a Peruvian through and through, just as you told the local newspapers 10 years ago: “I am Peruvian, sir. In school I learned to revere Grau and Bolognesi, just like any other child born in my country. I am Peruvian and I love my country as much as anybody else. The national anthem is my anthem.”

Toda’s statements, as cited by Tsuboyama, were not gratuitous. Why did the cyclist, born in 1935 in the city of Huacho, Lima Department, have to reaffirm his status as a Peruvian, as if his attachment to Peru had been questioned?

To understand his words, we have to go back to 1954. Teófilo Toda had earned the right to represent Peru in a South American tournament to be held in Uruguay. The young Nisei had his papers in order, but on the eve of the trip to the international competition, Peruvian authorities refused to grant him a passport. He was unable to make the trip.

He was never given an official explanation for the refusal, according to the book Peru Was the Future (El futuro era el Perú) by journalist Alejandro Sakuda. However, the real reason was obvious. Peru’s president at the time, Manuel Odría, discriminated against the Japanese immigrants and their descendants.

Although the unfair decision prevented him from competing in Uruguay, Toda was widely liked and received support from newspapers such as Última Hora, which roundly criticized the discrimination: “How can one justify denying a Peruvian, the son of Japanese immigrants, the rights bestowed by citizenship? In our estimation, in terms merely of common sense, this act is offensive to the nobility, dignity, and basic essence of human character.”

It was in this context, when the government denied him the right to compete for the country in which he had been born, that Toda declared, “I am Peruvian and I love my country just like anybody else.”

A NIKKEI IN TOKYO IN 2020?

Teófilo Toda retired from cycling in 1965. On September 14 of that year, in a two-page article, the newspaper Diario Extra emphasized that with Toda’s retirement after 16 years of racing, “the last lines of a brilliant page in national cycling have been written.”

“The Nisei cyclist abandons the track, but laden with glory,” declared the national newspaper.

In the interview with Extra, Toda referred to his participation in the Tokyo Olympic Games. “It was a wonderful experience that I will never forget,” he said, adding that he was grateful to sports for enabling him to visit the land of his parents. Although he was not a medalist in Tokyo, just being able to participate was a major achievement.

Japan’s capital will once again host the Olympic Games, 56 years later. Luis Toyama wonders whether at Tokyo in 2020, as in 1964, would there be any Nikkei athletes competing in the land of their ancestors. Although times have changed, he can’t help imagining what it would be like today to finance the dreams of an athlete as he and others did, thanks to their activism, more than 50 years ago.

© 2018 Enrique Higa