“Army trucks would pull up and someone would shout down, ‘How many in your family?’ And they would just throw the toilet paper and you had to go pick it up. And that lack of human dignity, it just went on and on.”

— Mitsuki Mikki Tsuchida

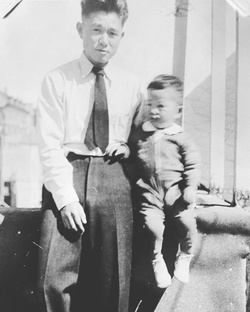

When I first started asking my dad about vivid camp memories, my dad would tell me how the alkaline sandstorms used to force the kids to run and hide, or that the piercing stench of the Santa Anita horse stables has never left him. He used to talk about taking a shower under the the enormous nozzle made for the horses would frighten him, and how he hardly saw his father, because he was arrested so many times for unruly behavior.

And now when I ask about camp, my dad tells me about the deep mental wounds the experience cast upon him: How he was beaten by the Japanese teachers in Tule Lake; how his lack of English skills after camp became a source of shame; how he’s spent his life burying it all into the recesses of his memory. “For a while, I was kind of self-conscious about how I looked. We didn’t know what we were being condemned for. It didn’t take long to know that our crime was that we looked like the enemy.”

My dad’s memories are also the only link to understanding what my grandparents may have gone through, as my grandfather Tom passed away when I was eight, and my grandmother Itsuye and I could barely communicate. Perhaps even if I could speak Japanese, she was the kind of woman that light-heartedly laughed at my questions, brushing them away. My grandfather’s anger at their imprisonment compelled him to be vocal–often confrontational–and he was targeted by the FBI several times over the course of the war. He nearly made the decision to go back to Japan with my dad and grandmother, but after discovering that Japan was actually losing the war (contrary to what he believed), they stayed. He voiced his disappointment with the treatment for the rest of his life and was writing a memoir until he suffered a stroke. But his writings are lost, and this is where I feel indebted to pick up the pieces.

A note about the Manzanar pilgrimage photos: Though our family was not in that camp, it was the first pilgrimage my dad and I attended together. While the scenery may be different from Topaz and Tule Lake, my dad put it best with this observation about the facilities: “You can’t even tell the difference from one camp to the other. They were exactly the same.”

For his willingness to be so open and forthcoming about his memories, I’ll be forever grateful.

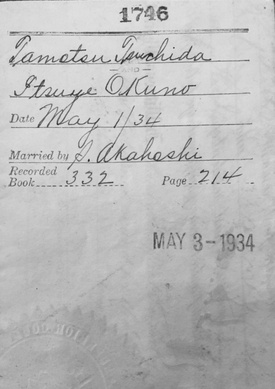

How did Grandma and Grandpa meet?

In Loomis where Grandpa was born, they were trying to arrange for him to get married to one of the sisters of the Ito family and to work on a fruit farm. He didn’t want to farm, so he fled to San Francisco. He was attending adult night school where he met my mom. She was only 17 years old and he was ten years older. Seven or eight months after they met, they got married in May 1934. Now that was not uncommon because there weren’t a lot of ladies around to be married. So that age gap was very prominent in the Japanese community. But my dad treated my mom like a young girl.

Do you think there was love in their marriage?

There was never any holding hands or talking. I’d see my mom cry occasionally, before the war. My mom wasn’t that literate or educated. And my dad was writing like a fiend when we were separated in the camps – he used to pressure my mom to write letters to him. I didn’t see any kind of sweet tenderness. I didn’t want my relationship with a woman that way when I grew up. I used to get examples of how men treat ladies by watching movies.

Was it just a convenience for them to be married?

I guess my dad proposed to my mom and instead of being all alone, with only her sister in San Francisco, she said yes. But my mom’s sister objected to him. She did not like him, so there was a friction there.

What were they doing for work?

They were cleaning people’s homes. So my dad was doing janitorial work. One day he was lighting a boiler in the basement and didn’t know the gas was on, and he lit the match. Then he was blinded. He used KIP and always kept a bottle of that, it followed us from camp to camp. Our next door neighbor at Tule Lake, the mother accidentally spilled hot water on the daughter. He smeared KIP all over her.

Do you remember a typical day in San Francisco? Who was watching you while they worked?

There was a man a couple of blocks down who owned a shoe repair shop who would watch me. Or sometimes Grandma and Grandpa would take turns, or Grandma would take me to her work.

Do you remember the day Pearl Harbor happened?

I got some hint that there was a war in progress and that it involved Japan. That’s where I became aware of my Japanese heritage. I also became aware I was growing up.

There was a Chinese laundry on the corner. My mom would get off the bus and they would see my mom and laugh, or catcall. She would get irritated and yank me along. They were already talking about how the Chinese and Japanese didn’t get along. There were so many bad words they would call each other. Real bad words. Chankoro Shinajin (Chinese people) But they would use chankoro — it’s like saying Jap.

I think I told you when I went to go take a Chinese girl out on a date in high school, her mother wouldn’t let her go out. I go to the house and the girl says, ‘Yeah, you’re Japanese.’ [laughs] And I just say, ‘Yeah, I am. And you’re Chinese.’ And she says, ‘I’m sorry my mom won’t let me go out with you.’ Even that, it goes back to the time when Japan was invading China.

Was there anything else that made you aware something bad was happening?

One day all the Boy’s Day dolls were out. I came home after we were set to go to camp and the house was already bare.

And there was this nice white lady talking to my mother, but my mom was about to give all of my dolls away. And I just had a fit, I was assertive. I said, ‘No!’ They were all stacked up and I put my arm out and said ‘no.’ And the lady said, ‘Oh, it’s okay.’ Then it was wrapped in paper, and we left some of our few belongings in a garage somewhere. I don’t know who, but it was someone in San Francisco. Obviously it couldn’t have been a Japanese family.

You used to tell me the story of grandpa getting his camera confiscated.

There was a curfew in effect, I don’t think you could be out in the streets at some ridiculous time, like 6:30 at night. There was a map of shaded areas that were restricted to the Japanese. He was in the wrong area.

But how could you tell? You live there and I could see my dad being ignorant of that fact. I know that because he retold that story, never to me. And then my mom used to say that we weren’t rich but he was spending money on the camera and it was taken away.

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on Octber 14, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida