Did he choose Poston due to it being on an American Indian reservation?

I think it happened to be under Collier’s jurisdiction and I think he had been through Arizona previously. I don’t think he had too much say.

If he couldn’t get out, why was that?

Because I think once you’re entered into the system, your file becomes part of the pile and it’s just the bureaucracy of the whole situation. And also, you’re immediately a suspicious element within the camp.

So during his time there he’s contacted by Reader’s Digest and they asked him to write about his time in the camp. He worked on two different drafts during that time but he wasn’t able to send it until he left the camp. The first paragraph is an amazing statement that really lays out his sense of the Japanese and Japanese American plight in the United States. It takes him about seven months – from May to November – to get out. And about five and a half month of that is writing continuous letters to friends asking them to contact people in the government.

Now Noguchi, the one lucky thing for him was that he didn’t really have a fixed address when he left, didn’t have a lot of things to concern himself with as he was improvising. He was already shuttling between the East and West coast.

This is another aspect of this exhibition, we’re not trying to position him as a typical story. His involvement is entirely voluntary. The activist within him that wanted to throw in. He’s a pacifist to begin with so he’s obviously not interested in getting involved with the war effort but what positive good can he do as an artist when things aren’t going well for him anyway? There are a million different stories and Noguchi’s is this weird asterix within the overall arc because he’s able to negotiate his way out.

I think strangely because his experience within the camp was negative for him, as far as the social aspect (not bridging the gaps that he wanted to), when he gets out, he’s in a very depressed state. He’s not as active in the groups that he was at the time. He kind of retreats into his studio.

So he really couldn’t make anything while inside Poston?

He finished the Ginger Rogers [bust], or at least made it halfway through. We know that because the marble for the bust was shipped into the camp. And there’s a correspondence between Ginger Rogers and he, saying he might need to see her for the finishing aspects.

So after Poston he moves back to New York and finds a studio on MacDougal alley in near Greenwich Village. Historically it’s an area where a lot of sculptors had a lot of live-in studios. So he finds this studio and lives in the studio for the next seven years. He comes back in really bad emotional shape. So just he immerses himself in work again. This is where he carves his first stone sculptures in years, and just the process is kind of nurturing. It’s so simple, going back to stone. We have here Noodle and Mother and Child which are some of the first sculptures upon coming back to New York. And you can tell by the scale of the stone that he’s still living rough. He needs to buy materials that are as cheap as he can get them so in many cases, I’m sure that the stone he got for Noodle was the biggest expenditure he had in years.

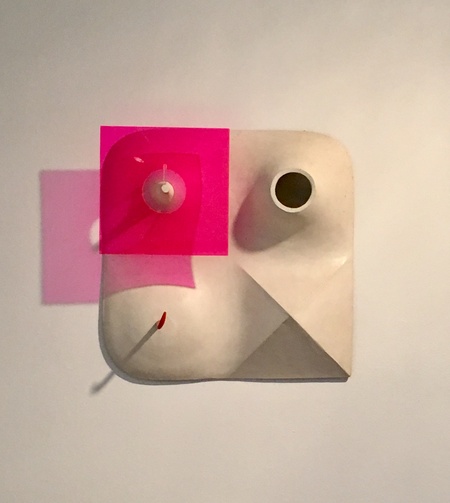

He does a couple of autobiographical sculptures at this time, they’re really reflections of his time in the desert. The magenta piece is called My Arizona and it’s has a very surrealist element. This is kind of abstracting the desert into a weird moonscape. For some reason he associates that sculpture with heat. I don’t know if the magenta personifies heat for him.

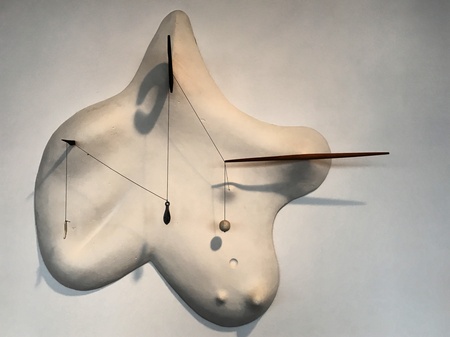

There’s another surrealist assemblage. This is a piece called My Yellow Landscape, again referencing his time in Arizona. This is really the beginning of him getting into the ideas of fragility, weightlessness, tension. One of these is never truly installed in the same way every time. It kind of speaks to the randomness of assemblage.

So “My Yellow Landscape.” Does that allude to the racial slur?

I’m sure it does allude–he doesn’t expressly talk about this sculpture.

He also did This Tortured Earth, which is said to be a response to seeing these photographs of aerial bombardments of North Africa from the war. He was a pessimist to begin with, he comes out of the Poston experience and once the atomic bomb testing and actual demonstrations were done, he has a very dim view of humanity. This for him is a very dark but also very black comic view, he sees this as conceptual sculpture: that you can sculpt the earth using bombs. He’s being very cynical and what it implies is violent. But at the same time there’s a certain element of levity.

How long did he experience his depression?

It’s not like it changes him overnight to get out of the camp and into MacDougal alley. He just dis-attached himself from everything as much as he could. He still had friends but he was really dedicated to his work, didn’t want to engage too much.

Around 1946 he is invited to be part of a show at MoMa called 14 Americans and he’s one of three sculptors that are chosen. It’s a body of work that he undertakes using cheap material, like wood. He develops this body of work that are like architectural pieces with pieces that are jutting through, or interlocking. This become his calling card, this is what he becomes known for in the mid-1940s:

He’s always been an artist’s artist, and this is just another level of that. He gets a little more notoriety; I there’s a story about him in Life magazine and Time magazine and they definitely look at the sculptures as wacky and weird. Noguchi at this point is interested in as much of the negative space as well as the positive space of the sculpture.

So during this period, his notoriety is sort of on the rise and he has another solo gallery show in 1947 in New York since the mid-1930s. So that gives you a sense of the opportunities to an avant-garde sculptor as opposed to an avant-garde painter. He doesn’t have a serious gallery relationship until the 1970s. It’s always kind of like a one-off experience for him. But industrial design keeps him afloat where fine art sculpture doesn’t. This is around the time he does the glass top coffee table by Herman Miller.

In 1948 he has a couple of different experiences. One of which is his friend Arshile Gorky commits suicide, just a few days after Noguchi has driven him up to the house in Connecticut. He and Gorky had a very brotherly relationship, they were close but had a lot of disagreements. It was quite a shock to him. It was another aspect of this depression in the 1940s. In 1949 he decides to pack up his studio and he applies for a grant from the Bollingen Foundation and they provide these fellowships to scholars to take trips around the world. He pitches this idea that he wants to study public spaces around the world and see how sculpture within public spaces influences culture. It’s very ambitious. So the entire 1949 and 1950 he’s traveling and at the end of 1950, it’s the first time he returns to Japan since 1930. He’s a little tentative but he is greeted totally positively by a younger generation of avant-garde artists, of through Western publications. So it’s the absolute opposite from his earlier experiences.

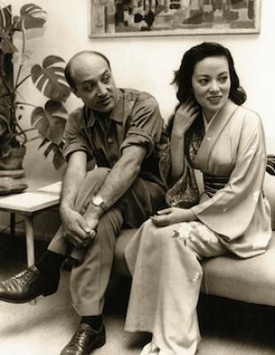

He’s getting his first public projects and he becomes a mostly Japanese for a few years. He marries a Japanese actress named Yoshiko (Shirley) Yamaguchi and they’re married for about three or four years. He sets up a house in rural Japan outside of Tokyo.

It does get a little more positive but it takes another nine or ten years for Noguchi to come out of the Poston experience in a positive way. His fortune has kind of changed in the 1950s. He does the UNESCO garden in Paris in the late 1950s and that really sets the stage for the last three decades of his career. He moves beyond the artist’s artist phase, he’s able to break even for the first time in his life. He has access to materials and projects, and essentially his successful years are from the 1950s on.

So it took a long time. And he and Yamaguchi were married for such a short time. Do you think that was due to both of them being artists?

Yes, absolutely. They both led unscheduled lives. She was pursuing projects, she was acting in Japanese movies, she did some work in Hong Kong movies. And in 1955 she was in a Samuel Fuller movie called House of Bamboo. And he definitely follows her around at certain points and does work in hotel rooms as she’s auditioning or acting. So I think there’s a tension. She is able to get a role in 1955 but that’s after two years of being denied a U.S. visa. Her own past is kind of complicated. She worked in film in the mid-1940s that were propaganda films in Japan, so she’s got a record with the U.S government. But she’s denied visas and Noguchi still sees himself as an American. He’s always got this dissonance that he wants to give equal regard to both sides of his heritage. He always feels the pull to go back to New York and yet he can totally appreciate the life he can lead in Japan. There’s more opportunity and it’s a more welcoming place to him. And that would exist throughout the rest of his life and career.

In the late 1960s he establishes his studio off the coast of Japan on the island of Shikoku. He’s re-engaged in a very positive way with his Japanese heritage.

Since it started off more contentious, he found his own way back. Did he and his father ever have a relationship?

There’s a thawing of tension in the time after WWII, and partly that’s because of his [Noguchi’s] own dispiriting experience, he wants to get back in touch. They exchange letters and Noguchi sends a care package to his father and his father’s family at least once. I think his dad died in the late ’40s, so he didn’t make it back in time. But essentially before his father dies, he tells his younger son that if his half-brother ever comes to Japan that he should get in touch with him. So his half brother seeks him out when he returns in 1950. Pretty much for the rest of Noguchi’s life, he shadows him as a photographer. He helps in the early time in 1950 as a translator, and follows him throughout Japan. I can’t say he’s reunited but he’s reacquainted.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on May 3, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida