“I begin to see the peculiar tragedy of the Nisei as that of a generation of transition accepted neither by the Japanese nor by America. A middle people with no middle ground. His future looms uncertain. Where can he go? How will he live? Where will he be accepted?”

— Isamu Noguchi from “I Become a Nisei” (1942)

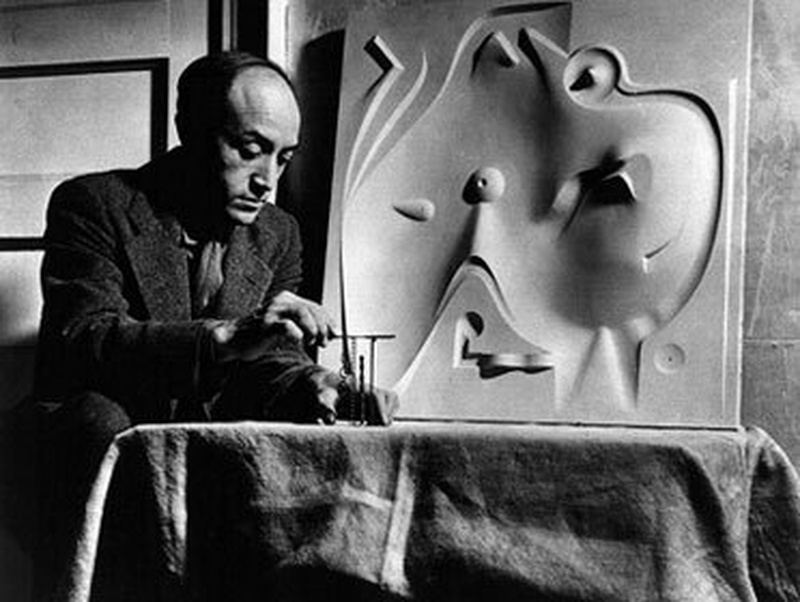

Sculptor Isamu Noguchi was as fluid a creator as he was in his racial identity. Born to Leonie Gilmour, a white American mother and Yonejiro Noguchi, a Japanese poet, he was by all accounts, an artist’s artist. Mentored by great European sculptors, commissioned by cities and governments, dancers and actresses, he seemed to channel his eclectic background to manifest his own world: Progressive, avant-garde, interpretive.

Known for his delicate Akari lamp designs, glass tables and sculptures in New York and Japan that are as much a part of the landscape as the buildings themselves, it took some time for Noguchi to be recognized as the fine artist he sought to be. Noguchi Museum Associate Curator Matthew Kirsch describes Noguchi’s predicament and lack of notoriety until he was well into his 60s. “He doesn’t have a serious gallery relationship until the 1970s. He’s well-regarded among his peers and yet it doesn’t really add up to much for him. He’s always just poor, he’s always getting by.”

But for as long as Noguchi struggled, he is now unequivocally regarded as one of the most influential avant-garde sculptors of his generation. His intuition for creating beautiful things transcended beyond stone, marble, and wood. He was cerebral; an intelligent and philosophical thinker who saw the world from a bird’s eye-view. “He is prolific in every way, not just sculpture. Prolific in meeting people as well. And he is as talented a writer as he is a sculptor,” says Mr. Kirsch.

Currently on display at the Noguchi Museum in Queens is a curation of his work during and after WWII entitled Self-Interned, 1942: Noguchi in Poston War Relocation Center (January 18, 2017 - January 21, 2018). As a New Yorker far removed from the West Coast upheaval of Japanese Americans, Noguchi was exempt from incarceration. But he was compelled to do something, to help in some way and contribute to the plight facing the community. And so he asked to be imprisoned in Poston.

In an unpublished Reader’s Digest essay Noguchi writes, “When people ask me why I, a Eurasian sculptor form New York, have come so far into the Arizona desert to be locked up with the evacuated Japanese from the West Coast, I sometimes wonder myself. I reply that because of my peculiar background I felt this war very keenly and wished to serve the cause of democracy in the best way that seemed open to me.”

Noguchi sought to beautify the camp, lead art classes, and get to know a community he was only minimally connected to. But what he was left with was disappointment. And what we are left with are beautiful renderings of the work that Noguchi created in the wake of his experience.

I walked through Self-Interned, 1942 with Mr. Kirsch, who shared his encyclopedic knowledge of Noguchi’s background, his artistic struggles and the pivotal moments that made him an activist for a Japanese American community he barely knew.

* * * * *

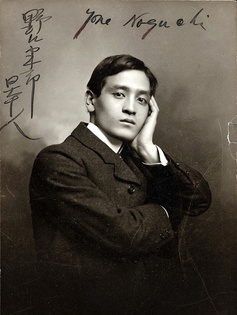

Isamu Noguchi was born in Los Angeles in 1904. His father was a Japanese poet, probably the most well-known poet of his generation in the Western world. He got to travel around the United States, spent some time in San Francisco, but also spent some time in Europe. I believe that’s where his poems were published first. In the United States he had met a woman who worked as an editor for him. Her name was Leonie Gilmour, she was very well-educated and an aspiring writer herself. She worked on editing and translating his work a little bit; she could work with the language a little bit but I don’t think she was super great at it.

And they had a relationship. Unfortunately, he went back to Japan while she was pregnant, they maintained regular correspondence. And this is up for debate with biographers when in fact he started his family. For a long time it was said they were married but in fact they were never married. So Isamu was born in Los Angeles and lived with a relative for the first two years of his life and then she decided because of their correspondence that she would bring Isamu to Japan to be a little closer to his father. And that is when she discovered he had a family.

Since he had left the U.S.?

Yes since he left the United States. So he grew up kind of at a distance from his father. Saw him like a handful of times throughout his childhood. He mainly was raised by his mother who was essentially a protofeminist. She was perfectly fine raising him herself and giving him a life but she did have to do various odd jobs to make ends meet. She taught English in English high schools in Japan and she also at certain points she sold trinkets, Japanese artifacts. She was a crafty person, resourceful.

There’s a story early on I believe that it was in Chigasaki where they moved to, she contracted a carpenter to build a house for them and she somehow insinuated Isamu into the project. This is when he was 9 or 10 years old. Try to get him to learn in the presence of this carpenter and he did become familiar with some aspects of woodworking. And this is related later when he goes back to the United States for his education.

He lived from about 1906 to 1917 in Japan. His mother kind of realized that as a half Japanese and half Western child, he was always going to be treated in a certain regard in Japanese culture. While at the same time he would’ve been conscripted in the military. So she had read about this progressive school in Indiana and decided to send him there. So when she relayed this to his father, he was adamantly against it. He wanted Isamu to remain in Japan. Supposedly there’s a story where he showed up on the day when Isamu was departing to the United States to try and get her to relent but they went forward with it.

So despite the new family, he still wanted to see Isamu?

Yes, however infrequently. There was still some bond he felt. And he [Isamu] was unhappy leaving, and this goes into the baggage between him and his mother throughout his life even though–it’s strange how he revisited his past life (everyone does) but like over the course of six decades of writings and letters I’ve seen instances where he’s kind of angry at his mother for changing his life in this way but also thankful that this probably led him on the path to being a full artist.

He went to this progressive school [Interlaken School] in Indiana but that school closed for various reasons, like financial difficulties as well as the onset of World War I. So Isamu had a very short time there. But the idea of the school was to raise the future business leaders of America by not only studying math and science but the idea of giving them a full immersion into hands-on processes. Building classes, art classes, carpentry classes, so it was meant to produce physical and mental specimens.

I should mention that at the time the school shut down, his name was Isamu Gilmour, and he went by the name Sam Gilmour for a number of years, kind of Americanized his experience. And Mr. Rumely [founder of Interlaken School] took an interest in Isamu and his background and he arranged for him to have a small apprenticeship in the studio of the sculptor Gutzon Borglum, who is probably most well known for Mt. Rushmore.

It was an unhappy time for Noguchi. Borglum didn’t take much interest in him, claimed he didn’t have any talent and Noguchi spent most of his time working odd jobs around the studio–taking care of his kids, modeling, and most of what he learned in his studio was because there were other craftspeople in the studio that would take time to show him different things.

Later Mr. Rumely among his circle raised his money to put towards Noguchi’s education. He ended up going to Columbia University and studying pre-medicine for a short time and that’s where his mother re-enters the picture, she comes back to New York in the early ’20s. And she had a vision of Noguchi’s future that was slightly different than his because of his father’s talent, she saw Isamu as being another artist.

So she lived in the Lower East Side, I believe, she noticed a school called the Leonardo Da Vinci school that offered sculpture classes and she pointed that out to Isamu and prodded him to go and try his hand in it again. And there he really excelled almost immediately. He was seen as a prodigy by the teacher that basically set up the school. His name was Onorio Ruotolo, he was an Italian-American citizen. Noguchi progressed so quickly that he dropped out, within a year or two. Ruotolo saw in him a lot of talent and essentially arranged for his first studios.

That kind of is a good set up for this show. There’s a portrait head. This is something Noguchi returns to again and again throughout his early years as an artist. He very quickly tired of representational and classical art, I mean, in making it. He was always interested in it but he wanted to set more goals for himself, new challenges for himself. And when he decides to become an artist in about 1924, he goes by the name Isamu Noguchi.

So no more “Sam.”

It was partly because his mother came back into his life, and she pushed him to become an artist. While he loved his mom, he also butted heads with his mom so I don’t know if this was him making his own way, using his father’s name instead of her name. It’s a little complicated.

So around 1926 he visited the Brummer gallery and it was one of the first exhibitions in the United States by the sculpture Constantine Brancusi and it basically changed his life. He was seeing what was considered avant-garde at this time. So Noguchi, this changes his path. Within a few years he applies for a grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation for a fellowship to travel to Europe. Once he gets to Europe he settles in Paris and that really kickstarts his involvement in the avant-garde. And there’s some debate about how quickly he meets Brancusi, even though they don’t speak the common language–Noguchi speaks at that point just English and Brancusi speaks French and his native Armenian. Brancusi is a very hands-on artist. This is another lesson and influence in his life. He works with Brancusi for six to eight months and they keep in touch for the rest of Brancusi’s life. Noguchi always considers him one of his masters in life.

So he returns to New York in 1929 and meets two of his future best friends and collaborators: Buckminster Fuller and also [dancer] Martha Graham. That collaboration is really for him another eye-opening experience because it gets him to think about the space around the object she designs. “The space between the viewer and the object.” He’s a very conflicted artist because in one sense he has these grand visions. For instance, in 1933 he has this idea that you could take an entire city block and make a playground out of shaped earth, calling it Play Mountain. He arranges a meeting with Robert Moses of the Park’s Department with this idea with a small plaster model and apparently the story is Moses laughs him out of the office. It’s a little too ahead of its time. In that sense thats something that keeps him going for the rest of his career. On the other side he is a skim artist, he needs to make a living so he returns to portraiture and like a lot of different artists from that era, he’s proposing projects to the Works Project Administration which was like the only patron of artists in the 1930s after the stock market crashed.

Not a lot of options.

Not a lot of options, especially for sculptors, too. There are a lot more painting projects. So in the meantime in the 1930s he does whatever he can to kind of get by. All throughout the 1930s he is a sociopolitical artist. He meets with other groups and kind of undertakes his first industrial designs. And this is in the wake of Lindbergh baby kidnapping.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on May 3, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida