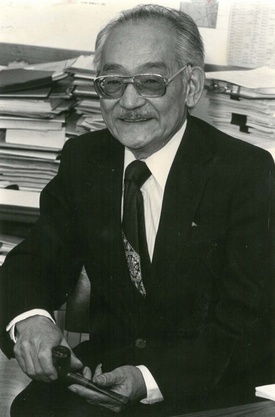

Holly Yasui is the youngest daughter of Minoru Yasui, the legendary Japanese American lawyer and civil rights activist. She is currently at work on a documentary film about the life of her father, titled Never Give Up! Minoru Yasui and the Fight for Justice.

On behalf of the Japanese American National Museum, I conducted an interview with Holly Yasui on the occasion of the Los Angeles premiere of Part One of her documentary, held at the museum on July 29, 2017. Part One covers Minoru Yasui’s life up until the end of World War II; the forthcoming Part Two will cover his lifelong work as a civil rights activist and his legacy for subsequent generations.

Excerpts from this interview were published on First and Central, the JANM museum blog, on July 26. We present below the interview in its entirety.

* * * * *

JANM: Your father was an extraordinary man. What was it like to grow up with him?

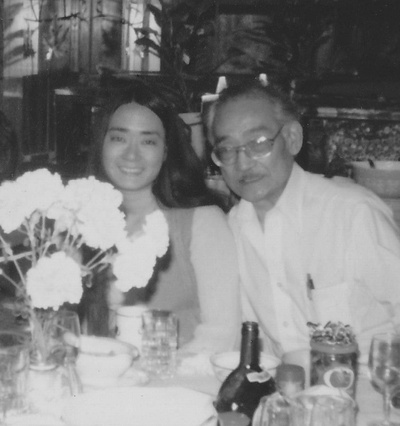

Holly Yasui: Though I didn’t know it at the time, it was an amazing experience to grow up with my dad, to be Min Yasui’s daughter. He was kind, loving, and patient. He taught me how to read before I started school, by reading out loud to me every night in bed before I went to sleep. Since I liked looking at pictures, he bought me a special illustrated encyclopedia. When I showed interest in writing, he gave me my first typewriter while I was still in elementary school; later, he gave me money to buy my first word processor when I was in college.

Though he worked almost all the time—he was a dedicated community activist, and like housework, that kind of work never ends—he was always home for dinner and he was always interested to hear from his family about what we did that day. It never occurred to me that it was unusual that he went out to meetings and events nearly every night after dinner and on weekends. For me and my sisters, that was normal—we thought everyone’s dad did that.

My dad and my mom took us kids downtown to his law office on Saturdays and Sundays, where they would work in the shabby, run-down rooms he rented in the small Japantown area of Denver. We would eat at the Mandarin Restaurant or Akebono or VFW Cathay Post, all run by Japanese Americans—I guess Chinese food was more popular than Japanese food back then. The owners of these small businesses and most of the others in Japantown were my dad’s clients, who often paid him in barter, so we ate for “free” a lot, got treats at the Kobunsha gift shop, and watched free movies at the Tri-State Buddhist Temple.

JANM: What is your favorite memory of your father?

HY: My favorite memory of my dad from childhood is travelling in our grey Plymouth station wagon all over the country. He was the consummate “networker”—confirming, renewing, and initiating friendships with Japanese American families in cities, towns, and rural farming and fishing communities throughout the country. He would attend meetings and give speeches at schools, community centers, churches, and barns. I later found out he was also working on applications for the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act, a federal program that between 1948 and about 1960 paid approximately four cents on the dollar for losses incurred by Japanese Americans due to their so-called “evacuation” (i.e. forced removal) from the West Coast in 1942. In between my dad’s visits, we saw the sights: Yellowstone National Park, the Grand Tetons, Mount Rushmore, Carlsbad Caverns, the Grand Canyon, the Liberty Bell, the Statue of Liberty, the various monuments in Washington, DC. My dad loved the outdoors and he loved to travel.

My favorite memory as a young adult was when my dad asked me to organize an event at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where I was a graduate student in Communication Arts. He wanted to inform people in Madison about the redress movement, which he was actively promoting all over the country. This was in 1981, when a Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) hearing was being held in nearby Chicago.

My dad was an extraordinary orator of the old school, and when he got up to speak at the event, I was kind of nervous because I knew that the hip young students weren’t accustomed to his style and might think he was weird. Sure enough, when he started speaking in his booming, grandiose, stentorian manner, members of the audience shifted in their seats, rolling their eyes and snickering to each other, and I felt embarrassed. But little by little, he worked his rhetorical magic, describing the American concentration camps in florid, heart-rending detail and the imprisonment of thousands of families whose only crime was being of Japanese ancestry. The auditorium grew silent, mesmerized by his overwhelming sincerity and passion. At the end, they gave him a standing ovation as he proclaimed, “We must NEVER let this happen again.”

JANM: What inspired you to make this documentary?

HY: In 2013, JANM invited me to participate on a panel with Jay Hirabayashi and Karen Korematsu to talk about our fathers and their legacies at the museum’s National Conference in Seattle, celebrating the 25th anniversary of the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. I met up with Janice Tanaka, who was filming the event for JANM and who had been a classmate at film school in the 1980s. (I dropped out, but Janice made good!) We got to talking, and the idea of a film about my dad was planted in my mind.

After the conference I went to Portland to visit Peggy Nagae, who was my dad’s lead attorney in the reopening of his WWII legal test case. We discussed the conference and my dad’s 100th birthday coming up in 2016, and we hatched the idea of a Minoru Yasui Tribute Project. Peggy took on the task of getting a Presidential Medal of Freedom for my father, and I took on the making of a documentary film. Peggy was successful in mobilizing a nationwide campaign to endorse the nomination, which resulted in a posthumous awarding of the medal by President Obama in 2015.

On my father’s 100th birthday, we screened a work-in-progress version of the film in his hometown of Hood River, Oregon. On March 28, 2017, we premiered Part One of the documentary, which covers his life up to the end of WWII. March 28 is Minoru Yasui Day in Oregon, and this past year was the 75th anniversary of the day he deliberately broke a military curfew to initiate his legal test case. I’m still working on completing the film, hopefully in 2018.

Never Give Up! – Trailer from Minoru Yasui Film on Vimeo.

JANM: Most documentaries are made by third parties. You are about as close to the subject as you can get. Does this make the process easier or harder?

HY: I think that the best films are made by people who have some kind of personal investment or interest in the subject. Yes, I am very close to the subject of Never Give Up! and that has made the process both easier and harder. Easier because I have access to wonderful materials that our family archivist, my aunt Yuka (my dad’s youngest sister) has saved—mostly photos but also documents and artifacts. Harder because I idolized my dad in life, but that’s not conducive to an effective portrayal of a complex human being.

I had originally planned to make a short tribute film that touched only on the admirable highlights of Min Yasui’s life, which doesn’t require much critical thought and would have been much, much easier to do. But the story cried out for more depth and breadth, especially in these times when we need to bring Min Yasui’s legacy and our community’s historical perspective to bear on the difficult issues of the day.

Thus, I found myself agonizing over the portrayal of my dad’s relationship with the Heart Mountain draft resisters and the FBI during the war, which is covered in Part One of the film, and I will have to look at how to fairly portray conflicts within the redress movement in Part Two. Also, given the fact that I am not a professional filmmaker by trade, it has been extremely challenging to learn what I need to know in order to not only make the film but also distribute it, get it out to the public.

JANM: If your father were alive today, what would his take be on the Trump administration and its policies?

HY: I think he would be appalled by the thinly veiled racism and bigotry inherent in many current initiatives such as the Muslim travel ban and the wall between Mexico and the United States, as well as anti-democratic efforts like supporting charter schools, taking away Medicare from thousands of people, and putting the fox in charge of the henhouse on environmental and civil rights enforcement. I have no doubt that he would vociferously oppose any and all policies rooted in discrimination based on race, religion, and/or national origin. I remember in the 1970s and ’80s, when the Iran hostage crisis sparked xenophobia and hate crimes against Iranian students, legal residents, and persons who “looked like” Iranians, he spoke out and unequivocally condemned such attitudes and actions.

As Director of the Denver Commission on Community Relations, a government agency charged with facilitating access to programs and services by underserved minorities (at that time, primarily Black, Latino, Asian, and Native American people), my father did have a great respect for our system and its elected officials. I think he would be disturbed by the tremendous lack of dignity and idiotic “tweeting” by the current chief executive.

JANM: What kind of advice do you think your father would give to young activists today?

HY: Never give up! Keep on fighting, stand up and speak out! Work for the common good, help to make the world a better place in whatever way you can, according to your own convictions and passions and life experiences.

© 2017 Japanese American National Museum