Can you please talk a bit about your own family history? Internment and where? How and when did they eventually get back to coastal BC?

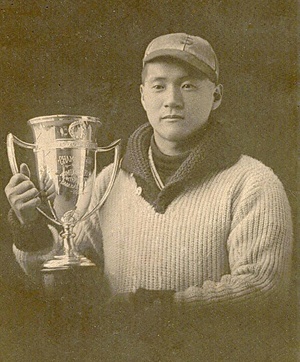

Lorene: My mother’s side of the family, the Dois, came to Canada in the 1800s from Hiroshima and settled in Cumberland on Vancouver Island. My grandfather, Kenichi Doi, was born in Cumberland. He worked in the mines, in the mills, and as a faller. He loved baseball and was a pitcher for a Cumberland team. He was recruited by the Vancouver Asahi and worked in a mill in Vancouver. There was a fire near the mine in Cumberland, and the family home burned down. He returned to Cumberland to help his family.

The family was shipped to Hastings Park, and then to the interior of BC. They stayed in Popoff, Bay Farm, and then Slocan City. My grandparents remained there until my grandfather died. A few years ago, my mom and I received a BC Sports Hall of Fame medal, a posthumous recognition, for my grandfather.

My dad’s side of the family came to Canada from Sendai, Miyagi ken, in 1906 on a ship called the “Suian Maru”. Everyone on that ship settled on Oikawa Island, Sato Island, and Annacis Island. When the forced uprooting happened, the names of the islands were changed to Don and Lion Islands. My dad died when I was little so I only found part of their story from the Oikawa journal that was turned into a book, Phantom Immigrants, and stories from my uncle before he died. My dad’s side of the family was shipped to Kaslo. My dad was pulled from school, and when Japanese Canadians were allowed to return to the coast, four years after the end of the war, he went back to Vancouver, where he knew a woman who could look after his baby sister. He was never able to pursue his dream of going to UBC to become a doctor. He had to look after his younger brother and baby sister.

While he was working to support his family, he did complete his high school education. It wasn’t just property and possessions that were taken during the uprooting and incarceration, it was the loss of family members who were separated or suffered ill health or death because of poor conditions, and it was the loss of education and opportunities.

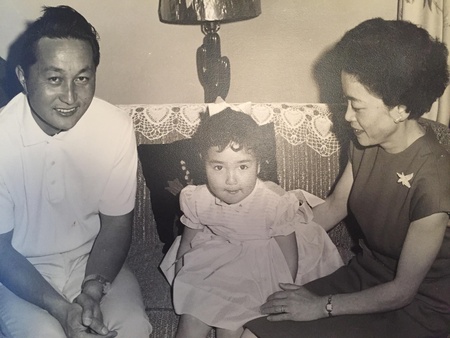

Sherri: I have an unusual history. I am adopted from Japan. But my Canadian family is Nikkei - my mother was born in Mission to a family who emigrated from outside of Kumamoto on the island of Kyushu, and my father was born in North Vancouver into a fishing family who originally came from Hiroshima. Dad’s father died when he was very young. Mom’s father, Shingo Kunimoto, was the head of the farmers’ co-op in Mission for many years. She was separated from her parents and all but one sibling by the events following Pearl Harbour. She had accompanied her older sister to Japan but then couldn’t return to Canada until well after the war ended. Her family, having been successful farmers in Mission, opted to go to Southern Alberta, like many of their neighbours, instead of an internment camp, with the dream of keeping the family together. Conditions were probably worse than in the camps initially. When Mom finally was able to return to Canada, she found her aging father and invalid mother living - literally couped up - in a dilapidated chicken coup in Picture Butte. My father also ended up in Southern Alberta - but some of his immediate family spent time in Hastings Park and then Taylor Lake. Mom and Dad met and married in Lethbridge, Alberta. Their story was encapsulated in media coverage for an award they received a Canada Cares Caregiver award in 2013 (B.C. couple honoured for caregiving)

And here’s a story that give more of my personal background: Sherri Kajiwara curates what it means to be Nikkei in Canada

My parents ended up back on the west coast because of my adoption, which was private. They promised my grandmother in Japan that they would do their best to ensure that I learned Japanese language and culture, which was a difficult promise to keep in Lethbridge in the late 60’s. We moved to Vancouver for my benefit. Many of the Kajiwaras had migrated back to the west coast earlier because of fishing, but only one sibling on the Kunimoto side had before we joined them. It would be more than a decade later that more of Mom’s siblings followed suit.

I often think of the opportunities that were lost with my own family members too. Can you talk a bit about any lasting legacy of the internment that are apparent in your own family? The larger community?

Lorene: When the government official told my grandfather he should ‘go back to Japan’, my grandfather told him he was born in Canada and Canada was his home. He wrote to the prime minister to tell him he was staying in BC and he wasn’t leaving. I didn’t know our history when I was growing up, but I knew it was important to stand up for what is right. It’s not just to do what’s right for our family, it’s about working together for safe, welcoming, healthy, thriving communities for everyone. It’s what drives me today. And I’m proud to say I’m Yonsei, fourth generation Canadian.

I am beginning to wonder about some of the health issues that affect subsequent generations. So much more is now known about trauma which results in cellular changes, and poor dietary and living conditions affecting future children.

Definitely the push to deny our culture and families not talking about the incarceration, and falsely believing the racism wouldn’t happen again if they “fit in” better, has had a huge impact on our community. Japanese Canadians have about 79% mixed unions compared to the next largest group at 48% is Latin American and 40% Blacks. The lowest are South Asians at 13% and Chinese Canadians at 19%.

When you look at the sites that were chosen, what kind of community emerges that we all shared before 1942?

Sherri: The pre-1942 community was largely in southern BC with significant primary resource (fishing, forestry, mining) communities elsewhere. The key word though is community. Wherever Japanese settled in Canada, they settled into Japanese Canadian communities. Prefectural bonds (where the early immigrants originated from in Japan) influenced where communities developed, but consistent in all areas was the strength of family, a strong spiritual and educational foundation - in every community there was some representation of a Japanese language school and a Buddhist temple - and an inspirational pattern of thriving and mastering whatever life held.

Do you see any gaps in the types of sites that were chosen or not?

Sherri: I feel the Evaluation Committee led by Heritage BC did an excellent job in choosing a broad spectrum of places for recognition. With over 200 sites to review, we were originally instructed to narrow our selection to 20, but after vigorous discussion, and extreme editing, we could only shave this down to 56. Luckily the Ministry and Heritage BC managed to work some budgetary magic, and all 56 sites were officially recognized.

What happens to those places now? Are they given any special protection? Will plaques be placed on those sites?

Lorene: We, the community group that self-organized when the government first put out the call, are continuing to press for a higher quality interactive map, and signage to make the recognition of the historic sites more meaningful, and to have this part of BC history included and taught in our education system. This is only one piece of what needs to be done to ensure our stories are known, and to make the history of BC and Canada more inclusive.

Sherri: This project was not about physical signs. The end ‘product’ from Heritage BC is a map and submission of all recognized placed into the National Registry. The Heritage BC sites can be seen here.

Please know that each place will have a full SOS (statement of significance) which is still being written by staff at Heritage BC with consultation of the Evaluation Committee. Full SOS content will not be completely uploaded until Fall/Winter 2017. That will be the final output of the Heritage BC project.

However, remember the Japanese Canadian Legacy committee I mentioned previously? The grassroots community collective that was born of the Heritage BC Significant Places project? They are pursuing talks with the Ministry of Transport and Parks Canada to have official signage markers for the road camps and internment sites that Japanese Canadians were incarcerated at. And the Vancouver Japanese Language School successfully received a BCMA Canada 150 project grant to create an interactive visitor experience based upon the Heritage BC recognized places.

What are your hopes for how BC and all Canadians remember what happened to our JC community contributed to the building of Canada for future generations to come?

Lorene: Japanese Canadians have been here since the 1800s. The first documented Japanese Canadian is in 1877, 140 years ago, but there are many stories being uncovered and also, Indigenous oral history that suggests earlier contact. Our ancestors struggled, endured much racism and hardship, and they survived and thrived. Their contributions are everything they did as individuals and families in their communities, and as workers, pre-war and post-war. They were in mining, mills, fishing, farming, shop keepers, inn keepers, restaurant owners, administrative workers, chefs, teachers, doctors, lawyers, photographers, writers, artists, musicians, performers, architects, newspaper editors, government workers, soldiers, scientists, and they created and produced, and started organizations, unions, and companies.

I want everyone to remember Japanese Canadians are Canadians who contributed a lot, and continue to contribute.

Sherri: Just as our ancestors who lived through the 1940s have always tried to teach - never let the atrocities of the Second World War be repeated - my hope is that this 75th anniversary year will be informative, educational, and inspiring not only in BC but throughout Canada.

There was silent suffering and gaman (enduring the unbearable with dignity) from the Issei (first generation), many to their graves, which genetically transmuted to their Canadian-to-the-core Nisei (second generation) offspring who survived the internment years. Despite sparks of reunion and storytelling since the 1980s, many third, fourth, and fifth generation Nikkei are only now learning of this dark time in our nation’s history. My hope is for a greater understanding of our community’s past. My hope is for healing, sharing, and preservation of an important piece of our history in this country.

Any final words to the greater community about the importance of this?

Lorene: The historic sites project is just one piece of the work that is happening, and more needs to be done. We must organize, and make sure our stories are embedded in the history of Canada, and that our stories are shared and learned in our education system. Our history is not limited to historical injustice, but it’s crucial people know about and understand the uprooting, dispossession, and incarceration of Japanese Canadians was wrong, otherwise we keep repeating the errors of the past.

Sherri: A mere 75 years ago there was an attempt to erase the existence of Canadians of Japanese ancestry on the westcoast of this country through a perfect storm of fear, racism, and war. Given that today the world faces those very same vices aimed at different faces in different places, the JC historical experience is even more relevant than ever before. Our community not only survived but has thrived.

The Heritage BC sites can be seen here.

© 2017 Norm Ibuki