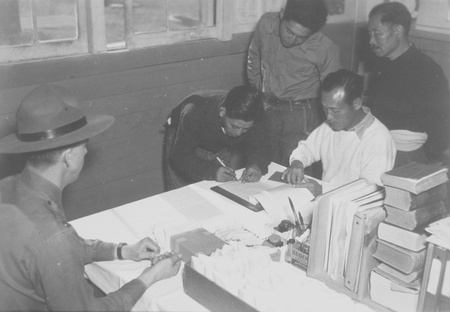

Isamu Carlos Shubayama, the son of Japanese immigrants, was born in Peru in 1931. When he was still a boy, his parents, siblings and grandparents were arrested in Lima in response to a request from the U.S. government in 1944. The Shibayamas were taken to the United States, where they were held in detention for two years at a concentration camp in Crystal City, Texas. During the war, the young boy's grandparents were exchanged for citizens of the Allied countries, and Isamu never saw them again.

Shibayama, now 86 years old (going by the name Art), is a U.S. citizen and still has the strength to demand justice for the human rights violations committed against his family by the U.S. government. On March 21, 2017, Isamu attended a hearing at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), part of the Organization of American States (OAS), to proclaim the reasons for his grievance. Thirteen years ago, Isamu and his two younger siblings filed a lawsuit with that international organism to demand compensation and a well-deserved apology from the U.S. government.

Although the Inter-American Commission does not have the authority to force governments to abide by its rulings, if the Shibayamas were to succeed in their lawsuit it would constitute public recognition of the flagrant legal violations committed by the governments of the United States and Peru against a group of citizens who had not committed any crimes. The pretext under which the U.S. government detained Japanese Latin Americans was the accusation that they were "illegal foreigners" when in reality it was the authorities of that country who arrested them and confiscated their identification papers.

Once the United States entered the war, its citizens of Japanese descent became victims of that government's persecutory policy. Through an executive order issued in February 1942, President Roosevelt ordered the detention of more than 120,000 people in 10 concentration camps. Some Japanese Americans filed lawsuits immediately after the concentration order was issued to prevent such an arbitrary action. Unfortunately, the courts threw out those lawsuits. However, decades later, the perseverance of Japanese Americans resulted in a great triumph with the signing of the Civil Liberties Act by President Ronald Reagan in 1988.

The Act authorized compensation of $20,000 and a formal apology from the U.S. government to its citizens who had been unjustly imprisoned. The Act also stated that racial prejudice and war hysteria had caused these violations of citizens' rights. This victory by Japanese Americans forced the U.S. government to agree to compensation of just $5 million and a tepid personal apology to the Japanese Latin Americans who were also detained. This offer was rejected by the Shibayamas, since it was clearly discriminatory and unjust.

The enormous suffering that the U.S.’s persecutory policy caused the Shibayamas and the more than 1,800 Japanese and their descendants who were sent to the U.S. from Peru can never be healed by any sum of money. That's why the Shibayamas want, more than anything, to raise awareness about their case and ensure it serves as a precedent so that no one, from any part of the world, has to endure what they suffered, as Isamu stated in his hearing before the Inter-American Commission.

The persecution of Japanese people wasn't limited to the United States and Peru. Across the continent, Japanese immigrants and their descendants were victimized by the U.S. government. In addition to to the 1,800 Japanese Peruvians, close to 400 people were taken from Panama, Colombia and nine other Latin American countries and placed in concentration camps in the United States. It should be noted that the Mexican government refused the request to send immigrants to the United States. However, a group of fisherman living in the port of Ensenada, Baja California were arrested after arriving in the port of San Diego and interned in the same camps, accused of being “foreign enemies” even though some of them were already naturalized Mexican citizens (see “La guerra de odio y persecución contra los emigrantes japoneses en América. ¡NUNCA OLVIDAR¡” [Spanish]).

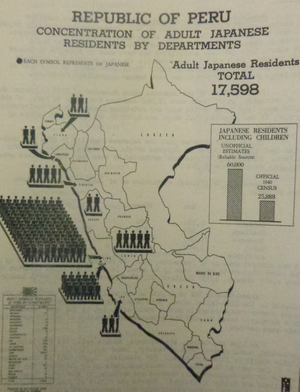

It is also important to emphasize that persecution and harassment of immigrant communities throughout the continent did not start with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Decades before, in the face of Japan's advance as a great imperialist power in Asia in the early 20th century, the U.S. War Department requested that its embassies throughout Latin America report on the number and activities of Japanese immigrants (starting in 1910).

In parallel with the U.S. government's surveillance policy, xenophobic attacks against immigrant workers in the United States and Peru had been occurring since they began arriving in the early part of the century. In the United States, restrictive laws were enacted to segregate the children of immigrants in San Francisco public schools in 1906. Years later, a law was passed that prevented immigrants from buying farmland, and they were forced to transfer land they owned to their children, who were U.S. citizens by then. Finally, in 1924, the U.S. president signed a law that prohibited more Japanese immigrants from entering the Unites States and also banned those who had lived there for decades from becoming citizens, allegedly to prevent "racial contamination."

By the 1930s, the differences between Japan and the United States, in defense of their imperial interests in Asia, had widened. This situation resulted in even more surveillance and harassment by the U.S. government of Japanese interests on the continent. As the war loomed, the FBI and U.S. intelligence began to track not only the movements of Japanese diplomats on the continent, but they also considered immigrants established in various Latin American countries to be "fifth columnists"; in other words, part of an invading army installed in America to serve the Japanese imperial government.

Once again, Peru was the setting of the most serious event that immigrants faced prior to the war. Spurred by rumors, angry mobs looted and attacked Japanese businesses, based on the mistaken belief that they contained weapons caches to be used to overthrow the government. In the anti-Japanese atmosphere that existed throughout the continent, in addition to the animosity between the United States and Japan, immigrant communities began to experience the war even before it broke out. At the time, the FBI kept detailed information on immigrants, their organizations, schools and their preferred activities in every country in America.

Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor only heightened mistrust and hatred against immigrants throughout the continent. Governments in the region were then able to implement a detention policy that resulted in the creation of internment camps for immigrants in several countries. Furthermore, their personal property and real estate were confiscated, with the support of most citizens. Fear of a supposed "Japanese invasion" that would be aided by immigrants was used to justify internment of Japanese immigrants and their descendants, who were said to represent a threat to the security of the continent given the war against Japan.

The battle being fought by the Shibayamas in the continent's human rights defense organism is expected to be a long one. Justice may take some time to arrive; hopefully the Shibayamas' precarious health, due to their advanced age, will enable them to embrace it. But in addition, the Shibayamas' struggle has recently become even more important, for two reasons: 1) No Latin American government has ever recognized the many violations committed against Japanese immigrants, much less apologized for them. 2) Racist, discriminatory and persecutory elements–which have never completely disappeared from U.S. society–have been unleashed once again with great power by the leadership of that country's very own government.

© 2017 Sergio Hernández Galindo