In writing this remembrance of Minoru Tamesa, one more memory of Min’s father, Uhachi Tamesa, comes to mind. My Jichan (grandfather) Nisaku Araki was a friend of Uhachi’s. On one of Uhachi’s visits to our house, I remember hearing raised voices from the kitchen, almost as if Uhachi and Jichan were having an argument. Such raised voices were unexpected and different from the usual low murmurings of polite conversation, so I peeked into the kitchen alcove, where they were seated around the table. Their voices were raised but both had smiles on their rather flushed faces, so they weren’t angry. Eavesdropping, I realized that they were having a bragging match about their respective grandchildren!

Searching a commercially available database, I found the name “Minola Tamesa” in the University of Washington yearbook of 1927. He was listed as a member of a UW scholastic and activity fraternity known as Purple Shield. Min often went by the name of Minola, and he would have been 19 years of age in 1927. I believe that Min attended UW in 1927 and excelled in his studies. My cousin Paul remembers that Min was interested in architecture. Undoubtedly, circumstances prevented him from completing his studies.

Before World War II, the Tamesas raised chickens, sold at the Pike Place Public Market. They prospered in this business; Paul recalls seeing a photo of the Tamesas’ Kelly Springfield gas-powered truck with solid rubber tires and wooden spokes. It seems the Tamesas were driving a truck at a time when everyone else, like my Jichan, was driving horse-drawn carts! Later though, the orchard fruits, especially peaches, became the best-remembered product of the Tamesa farm. [For more about life on the Tamesa farm, look for the upcoming remembrance by Dave Sabey, a friend of my cousins who worked on the farm as a youth.]

Researching the Tamesas in online newspaper archives, Ken Izutsu found that the Tamesas converted their chicken-raising business to a peach orchard in 1928—the year after Min entered UW. Min probably withdrew from UW because he was needed to set up the peach orchard. 1929 brought the Great Depression, likely ending forever Min’s college dreams.

I had long been concerned about Min’s physical safety as well as his spiritual health during the three long years he spent at Leavenworth because of his draft resistance. In doing research for this article, however, I uncovered a few facts that helped to assuage my fears.

My cousin Lillian gave me the telephone number of a former tenant of the Tamesas, whom I shall call “Mrs. C.” I spoke to this fine lady who shared her fond memories of Min with me. She had seen graduation certificates for Min for classes he had taken in fruit grafting and foundry work at Leavenworth. I knew then that Min had been preparing all along for a new life after he got out of prison! Clearly his spirit was not broken and he was already looking to the future.

Sensing that ghosts of the past were asking to be heard, I decided to re-watch Conscience and the Constitution, Frank Abe’s 2000 documentary. Min is not mentioned by name in this video but his photographs and his name appear on many documents that were filmed. In the video, Frank Emi, a leader of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee, described how many of the Nisei draft resisters, Min among them, were skilled at judo. Several of those men gave a judo demonstration at Leavenworth, during which much larger opponents were defeated. After that, the Nisei resisters were given a wide berth by the criminals who surrounded them. Thanks to the “ghosts” who spoke through this video, I knew that Min embodied gaman throughout his life. It took leukemia to wear him down to an early death at 56.

One memory that Min, my cousins, and Ken Izutsu all had in common was working at the Olympic Foundry. Izutsu remembers the foundry’s owner, John W. Kucher, as a man who was a friend to Japanese and Japanese Americans; the foundry was one place where Japanese Americans coming out of camp could still get work and fair wages. Min and the others all worked there at one time or another.

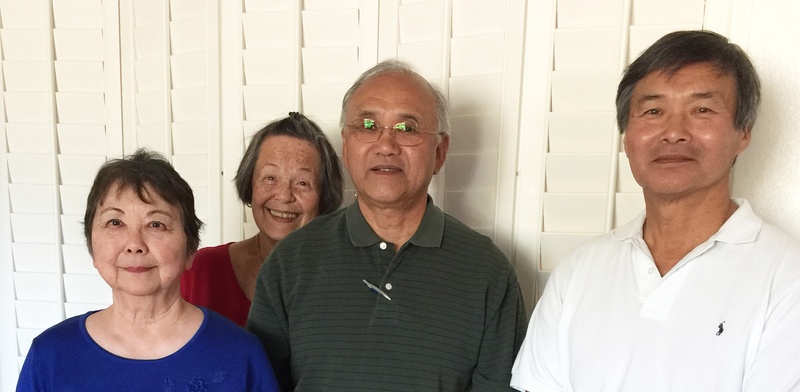

In gathering information for this article, it seemed that everyone I contacted wanted to share positive memories of Minoru Tamesa. How extraordinary to find that Min is very well remembered and with great admiration by many people, 53 years after his death! Thanks to Discover Nikkei, Ken Izutsu, Dave Sabey, Brian Niiya, and my cousins Bobby, Paul, and Lillian Sako, I have come to know Minoru Tamesa better than I ever knew him when I was a child. I hope others will come to know the fine person he was too.

© 2017 Susan Yamamura