On the night of April 21, 1977, fourteen armed men dressed in civilian clothes invaded the law office of my father Oscar Takashi Oshiro and his partner Enrique Gastón Courtade. They were forced to get into a Ford Falcon and set off for an unknown direction with no return.

That same night my mother, Beba, as everyone called her, my brother Leonardo and the person writing these lines were on the eighth floor of an apartment located on Avenida Acoyte 222, in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Caballito. Something was boiling in the kitchen; The table was ready for dinner but in the end it was left untouched, with the white porcelain plates and the orange and white flowered cotton tablecloth. There was something strange in the air that day, my mother was very agitated and didn't talk much. It was strange because she used to talk a lot. I was sitting on the cold black leather couch, wrapped in a wool blanket that stung against my skin. I was trying to concentrate on some television program. At just five years old, I knew that we were waiting for my dad to come home from work.

I had no idea of the time but I did know of everyday life: the sun was going down, my mother was finishing her work at her father Juan's textile company in the Boedo neighborhood. We got into the truck with my maternal grandmother Teresa, my grandfather at the wheel, they took us to the apartment, about twenty blocks away that went by very quickly while we sang traditional folk songs. At home my mother began to prepare dinner and moments later the sounds of keys were heard: the door opened while I ran to hug my dad to give him stories and drawings that I had created for him. On Sundays we went to lunch in the Pompeya neighborhood, to my paternal grandparents' house; Ikuko and Katsu Oshiro. Thus my days passed without too many events and they all blended together with some exceptions, like that April day that I was counting.

That night my mother continued to look at the clock on the wall and I stared at the white front door, waiting to hear the sound of the key turning in the lock. Suddenly we heard the sound of the elevator stopping on our floor and the squeal of the metal door as it opened. We ran as if in a race towards the entrance, my mother opened the door and, disappointed, we greeted the neighbor from the eighth apartment “18” who was walking towards his home. My mother closed the door and we did the same thing again, but this time, sitting on the couch, my eyes closed without me being able to help it. My mother sent me to sleep in my room, where my little brother had been resting for quite some time. I fell asleep until my mother hurriedly woke me and my brother up. We went to my maternal grandparents' house. The twenty blocks that a few hours before were full of joy were now endless and my grandmother's songs had been replaced by an unbearable silence. I didn't dare ask and I could feel my mother's tension.

I knew we were about to arrive at my grandparents' house as soon as I saw the San Lorenzo de Almagro field that was right in front. We used to go there with my dad to watch Huracán-San Lorenzo soccer games, two classic local soccer rivals. It was a “secret” walk, so that my mother wouldn't worry. That night we went to Boedo, the beautiful memories and the places we visited with my old man already had a different flavor. My brother was two years old then and I was barely five. I knew that something bad had happened: it was the first time I saw my mother cry, while my grandfather Juan tried to calm her down. They both decided to go to my dad's studio in the Avellaneda neighborhood in the hope of finding him.

When Beba and Juan arrived, Takashi's red Citroën had all the doors open, the studio was in total disarray but there were no traces of Gastón or my father, luckily Juan and Beba arrived much later than the task group that was there. He had returned a second time to steal, break, burn documents and take Gastón's Ford Falcon. My old man's car had a hidden device that cut off the electricity to the alternator and prevented it from starting.

After a long time, Beba and Juan returned without my father. We moved to the house of Teresa and Juan, my maternal grandparents. My mother began the endless journey in search of Oscar Takashi Oshiro.

The Argentina of those years

During the stormy 20th century, Argentina suffered six coups d'état. The last coup d'état occurred on March 24, 1976 and is remembered as the worst of all due to the massive and systematic violations of human rights. During the last Argentine military dictatorship (1976-1983) citizens did not know very well what was happening; there were concentration and extermination camps, like in Nazi Germany, which were called “clandestine detention centers.” Citizens opposed to the military government were kidnapped in absolute secrecy and sent to detention centers. They rarely appeared again. The "disappeared" were workers, students, political and union activists, professionals, artists and intellectuals. All of them could have occupied important positions in the not too distant future. The military dictatorship destroyed all that human potential, through kidnappings, torture and illegal executions. The military stole the babies of those pregnant women who were detained. The bodies of the victims never appeared, the military tortured to obtain information and then killed and then buried the bodies in common graves, without names or marks. Other detainees were thrown into the void from planes in the Río de la Plata.

I still cannot understand how some human beings can kill others with such cruelty and without any charge of conscience. I have listened to the few soldiers who are imprisoned and none of them repented for the very serious violations of human rights. Most of them think and express when they can that their terrible actions were justified and justifiable. They see themselves as heroes and patriots.

In addition to the deadly repression, workers lost their rights, their union representatives were persecuted, imprisoned and eliminated, many factories were closed as they were imported indiscriminately from abroad due to the trade opening policies imposed by the military government. Profits were eliminated to promote internal industrial growth, which caused the destruction of Argentine industry, or at least its less concentrated fraction.

The Argentine military dictatorship used the word "disappeared" to designate murdered opponents. Not only was there an attempt to hide the killings and bodies, but there was also an attempt to erase the identity and history of thousands of people.

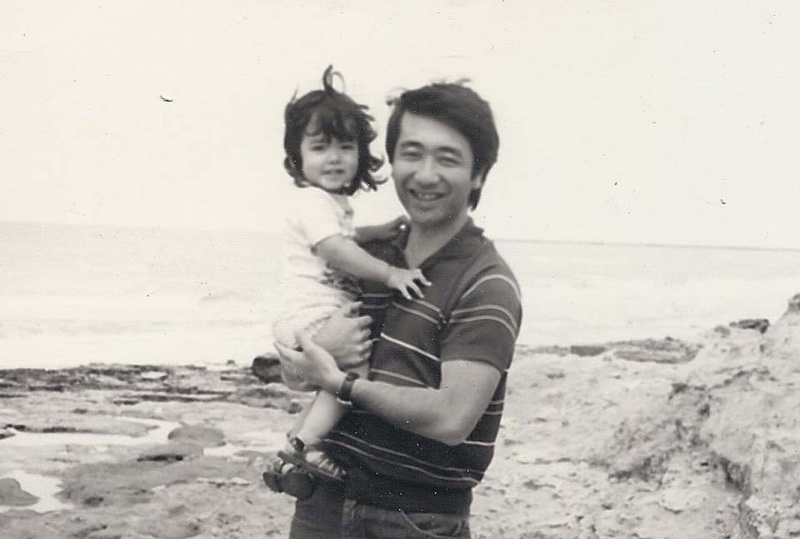

This is exactly what happened to my family. Oscar Takashi Oshiro was my father. The reader will hardly recognize that name, but for my family and me, he was the center of our world. My father was 36 years old when he was kidnapped on April 21, 1977. He was married to my mother Edvige "Beba" Bresolin. They had two children, Leonardo and Gabriela, who writes these lines.

We were a family like many others, surrounded by family and friends. We enjoyed vacations on the beach. We had dreams to realize. My family was an “intercultural” family; on my dad's side my relatives were Japanese from the island of Okinawa and on my mom's side, we were of Italian descent. At that time, it was not very common for people of Japanese descent to marry people from other communities. My father was very different, like the other sixteen missing Nikkei, he was not the typical “Japanese”, although my father knew the history of Japan, the language and was familiar with its traditions. He embraced the Argentine culture, he became completely “Argentinianized”: he played soccer in the second division for the Atlético Huracán club and he loved tango and folklore.

I don't honestly know what the other Japanese communities scattered around the rest of the world are like and what the characteristics of Japanese migration out of Japan were, but in the first part of the 20th century in Argentina, the Japanese arrived attracted by the economic opportunities that the South American country offered. The central idea of many emigrants was to earn enough to then return to Japan. After Japan's defeat in World War II (1939-1945), most decided to stay and adopt the country as their new home, trying to keep the cultural roots as intact as possible.

Nikkei in Argentina

The Japanese in Argentina formed a united and closed community. My father, along with his younger sister Yoko, studied the Japanese language at the Nichia Gakuin school, which at that time was on Finochietto Street, in the Barrancas neighborhood. They competed in athletics in the undokai, which were Japanese club sports competitions. My father practiced karate inspired by my grandfather Katsu who had studied at Shuri High School in Naha, Okinawa, where they taught karate as physical education.

The Japanese with their families were considered “guests” of the country, which meant that they remained on the margins of local society, that is, they married among themselves, and did not participate in local politics, but continued with their own lives without too many links with the Argentines. Many years later, my grandmother Ikuko told me that my parents took several years to get married because they did not want to accept my mother, since she was of Italian origin. They liked my mother as a person but at the same time they followed the customs to the letter, without questioning whether they were fair or not. During the courtship period, my parents took my grandfather Katsu or (“Antonio” as they nicknamed him) to watch boxing and to the theater. My grandfather really enjoyed the company of the couple.

My father wanted to change the status quo, he defied my grandparents' tradition and finally married whoever he wanted. He had that mentality, that trait of those who leave traces in the world. Everything my father did, he did with great passion. For many years I could not understand my father's passion for politics, his tendency to help workers, those most in need. Now after a long time of reflection, I understand that my father's feeling was similar to what I feel towards music and art. I had never understood before why, for my father, politics was so important. Probably because I somehow unconsciously blamed politics for considering it responsible for his disappearance.

My dad was a “hybrid” of two different cultures that he loved equally. When I remember him, I see him with a book in his hand, with his head buried in it, a gesture that denoted his thirst for knowledge. He took speed reading classes so he could devour more and more books. He spoke Japanese, Spanish, Italian and was learning French at the Alliance Française when he disappeared.

He wasn't the kind of person who did things halfway. My father turned words into actions. He studied law and one of his obsessions was the defense of workers' rights. When my father was in his second year of law school at the University of Buenos Aires, he decided to leave school and look for a job at the BTB metallurgical factory in Avellaneda to better understand the problems and needs of the workers. He became a union steward, although he was later fired during a factory strike in 1972.

© 2017 Gaby Oshiro