If Dad were alive today, I think he would have been simultaneously embarrassed and proud that something of his is currently on display in one of the world’s most prestigious and famous museums. And my late mother, would be standing right beside him smiling with amusement about the improbability of it all.

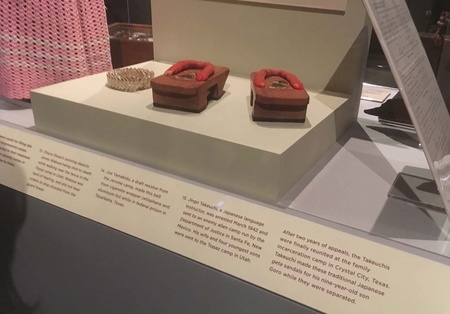

Yet since February, something of Goro Takeuchi’s indeed sits a few dozen steps away from Abraham Lincoln’s iconic top hat inside the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, Kenneth E. Behring Center. As part of a yearlong exhibit that opened in February titled Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II, his pair of childhood geta—complete with a possible copyright-infringing image of Mickey Mouse painted on top—have sat encased in glass under a spotlight in a museum that has welcomed four million visitors so far this year, while also being featured in the Washington Post, Reuters, National Public Radio, Japan’s NHK Television… and even the Irish Times(!). All of this prompted my wife Sheila to affectionately nickname them “Goro’s Famous Shoes”.

Months later, it still feels surreal thinking that it sat unnoticed and collected dust for over 50 years on a dining room shelf of our longtime family home in Santa Barbara. It wasn’t until my older sister Karen, my wife, and I were cleaning out our longtime home shortly after my 80-year-old father passed away in May 2015, did we find the footwear made by his father Jingo…the jichan who I never knew. Unfortunately, none of us, me, my sister, my older brothers David and Darren, or Dad’s younger brother Mamo—who along with my Uncle Kenji are the last surviving members of their generation—knew the story behind the geta’s origins.

With the words “Santa Fe” and “New Mexico” bordering above and below Mickey, it was safe to conclude that they were made during Jingo’s stint at the Enemy Alien Camp there. His ordeal began with his March of 1942 arrest by the FBI for the “crime” of being the headmaster at two language schools in Northern California while also helping establish the sport of kendo to the United States. Dad was seven-years-old at the time.

After a two-year separation from his family who were concurrently incarcerated at camp in Topaz, Utah, Jingo Takeuchi reunited with his wife Kiwa and the four youngest of his seven children at the Crystal City Internment Camp in southern Texas in 1944. Crystal City was a facility unlike the camps under the jurisdiction of the War Relocation Authority (WRA), It was run by the Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) and overseen by the Department of Justice (DOJ) operating within the prisoner-of-war stipulations put forth in the Geneva Convention. Crystal City housed not only Japanese and Nisei, but also Germans, Italians, and South and Central Americans of Japanese ancestry who were evicted from their country. The camp’s purported focus was to reunite families whose patriarch was originally sent to an enemy alien camp, but it was also used to assemble them for the purposes of prisoner-of-war exchange with Japan, Germany, and Italy.

While waiting for the approval of their request to stay in the United States following the war’s end (Crystal City internees living in the U.S. prior to the war were required to apply for non-repatriation if they wanted to remain in this country, including American-born Nisei like my father), my bachan passed away in a camp hospital due to heart disease two months after the war ended and five months before the rest of the family was finally released in 1946.

Uncle Mamo said that after his imprisonment and separation, the death of his 49-year-old wife crushed his father. Civically and culturally active prior to the War, jichan withdrew-declining job offers to be an editor at both Los Angeles’ Rafu Shimpo and San Francisco-based Nichi Bei newspapers, to quietly work as a gardener in Santa Barbara and raise four sons by himself-before passing away from the effects of a blood clot at 67 in Los Angeles in 1955-11 years before I was born.

Although family members shared a few stories at get-togethers over the years, the picture of who my grandparents were remained much like an abstract work of art that only maintained the essence of its subject. The details were left open to interpretation-with one 1928 photo of them as the only visual reminder…outside of jichan’s DOJ file, of my grandparents’ life together.

A few photos of jichan surfaced in recent years, but none of bachan and definitely no physical items were saved…until we found the geta.

I always knew that it would be selfish to just hold onto them forever, but I just couldn’t let them go right away. So for a while, I used them as an inspiration of sorts as I began a book project abut Uncle Keigo, my dad’s brother-a dancer who performed all over the world while dancing on The Ed Sullivan Show and in the movie version of The King and I (I wrote about the experience here).

Shortly after Dad died, I went to the final Crystal City Internment Camp reunion in Las Vegas in October 2015. Here, I got to know people who knew my family, wonderful folks like Hid and Etsu Kasai, Mas Okubo, Joe Ando, and longtime event organizer Toni Tomita. Toni’s family are unrelated Takeuchi’s, who nevertheless have treated me like we were kin. Writer Jan Jarboe Russell, who authored the wonderful book “The Train to Crystal City: FDR’s Secret Prisoner Exchange Program and America’s Only Family Internment Camp During World War II” was the keynote speaker. Noriko Sanefuji, a curator at the National Museum of American History who was also on hand to seek artifacts for the then upcoming visit.

Noriko’s presence conjured up a long-ago memory of Dad enthusiastically telling a local Congressman how impressed he was by the Smithsonian at a JACL picnic. It stuck out because the only things I remember Dad being impressed about in the past, were the 1970’s Oakland Raiders and when golfer Tiger Woods was dominating the links.

About a year after sending the geta to Washington, I went down to southern Texas to see the Crystal City site. It was quite emotional to see not only the place my bachan died in, but how dad’s life began to take shape. Something I chronicled on my Kickstarter page.

February 16, 2017 Washington D.C.

The evening started inauspiciously when despite being only a block away from the event, we were prevented from crossing the street for several minutes so that the newly sworn in President’s motorcade could pass by. Arriving several minutes late at the museum’s entrance an early 2000’s model Toyota pulled up to offload a group of people rushing into the same event. Figuring they knew where to go, I quickly followed the group, stopping only to exchange bows with the smiling man holding the door. It took me a few seconds of wondering where my wife was to realize that while she went through the correct entryway via the museum’s security check, I had inadvertently joined Japanese Ambassador Sasae Kenichiro’s group.

Oops.

Delicious as it was, the sushi paled in comparison in not only meeting Ambassador Sasae, but spending a delightful time speaking with his wife Nobuko-an accomplished translator-about the beauty of nature in Japan.

It was also a great honor to meet U.S. Senator Mazie Hirono, Congresswoman Doris Matsui-whose late husband Bob gave an award years ago to my Uncle Kenji, the JACL’s national president Gary Mayeda, and Karen Korematsu, the daughter of the legendary activist Fred Korematsu. John Gray, the museum’s director and of course Noriko warmly expressed their gratitude and appreciation, making me realize we made the right choice.

Just outside of the bright golden sign announcing the exhibit’s entrance, tables of items were displayed with museum staffers and interns educating visitors about each item. Once inside, the warmth of good cheer we absorbed at the reception was chilled considerably while we took several minutes to ingest the actual Executive Order 9066 that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt enacted two months after the start of World War II.

On the other side of the center island, lay the geta. On the flight over, I wondered if I my emotions would get the best of me, so I made sure to pack some tissues with me. But once I saw the familiar tiny “famous shoes”, I wasn’t so much sad-but more of a feeling of being awestruck that my family’s history was on display for millions to see. Once there, I could only repeat the words “wow” and “sugoi” over and over while looking at them.

When this offer came along, I wanted to honor a father who I often clashed with and disagreed with as a boy and a younger man, but later made peace with him enough where we actually became friends in the last few years of his life. Seeing the geta in the glass case was overpowering emotionally, yet there was still a lingering sadness present not from just the passing of Dad, but also that of my mother 14 years before him and how after essentially being orphaned at 11, lost the love of his life too early much like his father did before him.

Not ready to say goodbye, I kept going back to the exhibit for the next few days. Camping myself in a far corner, I watched people look at them. I mostly left them alone, but if they lingered or discussed them, I approached to tell the story-prompting tears, many of them my own. The most memorable meeting occurred on our last afternoon in D.C. when I approached a small group of middle school students. As it turned out, they went to Carden Country School in Bainbridge Island, in Washington state, a mere few miles away from Seattle where my jichan emigrated to this country. He lived for a decade here, marrying bachan and having the family’s first two children. These kids, who raised their own funds to make this trip, were along with their teachers and parents, enthusiastic listeners.

Kismet.

After taking photos and then saying our goodbyes, the lingering sadness that had been hovering over me the last two years seemed to dissipate considerably. I felt a certain lightness and knew I was ready to go home.

Closure.

Shortly after takeoff on our flight home, the Washington Mall came into view. As the museum appeared to shrink as we rose and pulled away, I said goodbye to the geta…I mean Dad—happy that they/he have a new home.

And if Disney’s legal department calls, I’ll tell them to contact the Smithsonian.

© 2017 Michael Goro Takeuchi