The untouched ground of America

I began to hoe

This virgin soil.Honda Fugetsu1

During the 1900s, many Japanese immigrants moved into agricultural work. At first, the Issei were drawn by better wages to work on farms. In 1909, farm laborers represented more than a quarter of the total 3,873 Japanese in Oregon. Known as buranke katsugi [blanket carriers], they were seasonal migrants, carrying blankets with a few other daily necessities. Many of these men subsequently invested their earnings and rose above the class of common laborers to sharecroppers, leaseholders, and farm owners. According to the Portland Japanese Consulate Report, the number of Japanese farmers jumped from 71 to 233 between 1907 and 1910.2

Japanese immigrant farmers tended to gather in restricted areas. Montavilla and Gresham-Troutdale were prominent among the many Japanese farm settlements in the eastern part of Multnomah County. Starting around 1904, Japanese emerged as berry and vegetable farmers in these areas. Land prices were high, from $500 to $800 per acre, so most Japanese were tenant farmers with three-to-six-year contracts. Initially, white landowners welcomed the Japanese on their land because they paid the highest rents, usually $15 an acre.3

Because of its close proximity to Portland, Montavilla was the first Japanese farming settlement with a sizable population. In 1908, 36 Japanese farmers held a total of 665 acres.4 Three years later, the community had approximately 200 Japanese residents with an additional hundred laborers during the harvest seasons. Half of the total acreage in the area was under Japanese control by then.5 The first Japanese producers’ association in the state was established here. Montavilla was indeed, as a Japanese immigrant writer called it, “the Japanese farm village” at the time.6

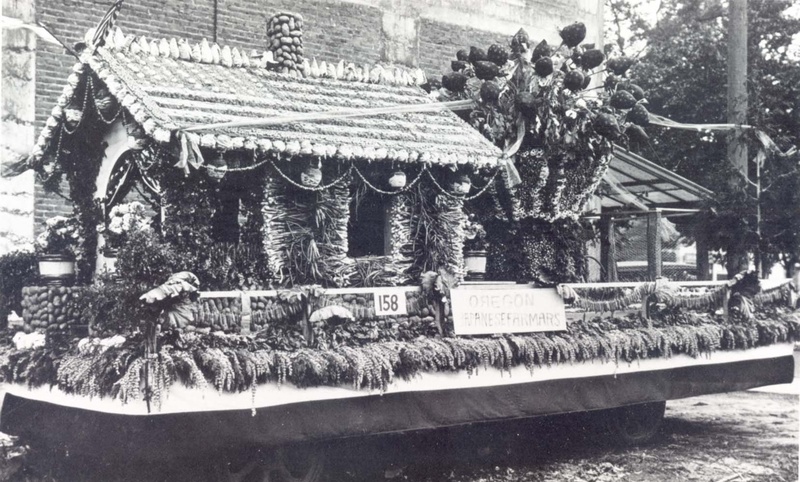

The Japanese farming settlement expanded further east, and the Gresham-Troutdale area became its center. By 1920, local Japanese farmers were reported to have occupied half of the acreage of raspberries, 90 percent of the strawberries, 30 to 40 percent of the loganberries, and 60 percent of all the vegetable and truck gardens. As did their Montavilla counterparts, the Gresham Japanese organized a farmers’ association in 1918 in order to market crops and purchase equipment and supplies. The Gresham-Troutdale Farmers’ Association had an initial membership of 50 farmers. In the eastern part of Multnomah County, there were almost 300 resident Japanese in 1920.7

Hood River, located some 60 miles east of Portland along the Columbia River, was another major farm settlement for Japanese immigrants. The small valley was undeveloped until the turn of the century. When Japanese immigrants first came to the area around 1904, they were neither tenant farmers nor field hands. Many were employed to cut trees and to clear land by local landowners. They were given five acres in exchange for clearing 15 acres under a unique working arrangement with their employers. This arrangement enabled the immigrants to become landowners without accumulating capital.8 By 1909, several Japanese owned five to ten acres by this method, and a dozen others were clearing land in order to acquire the acreage. In the years to come, Hood River became a very distinctive Japanese community in which most of the farmers were settled landowners.

Outside of Multnomah County, Hood River was the largest Japanese farming settlement. Many Japanese farmers appeared during the early 1910s. Between 1910 and 1913, the farming population in Hood River, Dee, and Parkdale rose from 12 to 53. Japanese land ownership went from 137 to 767 acres, while their leasehold increased from 73 acres to 105 acres.9 Thereafter, the number of Japanese immigrant farmers did not increase as sharply, but their acreage continued to grow. In 1920, some 70 Japanese were reported to farm 2,050 acres, of which they owned 1,200 acres. As a result, the average Japanese farmer in Hood River held larger acreage than his counterpart in other locales.10 This was indicative of the strength of the Issei farmers in Hood River.

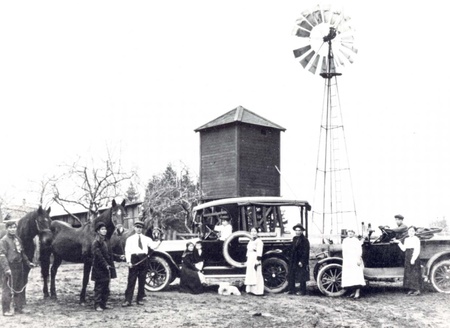

Masuo Yasui played an important role in the rapid development of this farming community. Born in Okayama Prefecture, he came to Seattle in 1902 at the age of sixteen to join his father and brothers, who were railroad workers. After going to Montana, he worked as a cook for a Japanese railroad gang. When he was eighteen, Yasui moved to Portland. After a few months, he found a position as a domestic worker with a white family and enrolled in night school. He learned English quickly and acquired a good command of the language. Working as a labor contractor, he became an active leader of the Portland Japanese community.

In 1908, Masuo Yasui established the Yasui Brothers General Store in Hood River with his brother, Renichi Fujimoto. When he visited the small valley community the previous year, he was impressed by the beauty of the area and inspired by business opportunities he saw serving the increasing number of Japanese residents. Furthermore, the local Japanese led the sort of life that he himself believed in: permanent settlement in America. Shortly after his visit, Masuo Yasui wrote a thirty-page letter to his brother, Renichi, in which he stressed this belief:

People always talk about “Going back to Japan as soon as possible.” Should it really be the ultimate goal to live an idle life [in Japan] with American dollars?...I hope that you summon your wife and make a peaceful home in this great land of freedom. What is the use of going back to Japan and spending the rest of your life in that countryside?”11

Yasui envisioned his store playing a pivotal role in the development of the Japanese permanent settlement in Hood River. Eventually, Renichi was persuaded to invest his savings in a general merchandise store.

The store became the hub of community activities for the Japanese living in the Hood River Valley. As Masuo Yasui had envisioned its mission, the store was a meeting place, an information center, a rooming house, a mail drop, and a travel and insurance agency for the convenience of local residents. Masuo, with his command of English, also served as a liaison between the Japanese and the local white residents, assisting the farmers in buying land and the laborers in finding employment. Opposing isolation from the white community, he urged his fellow countrymen to spread out and mingle with their white neighbors.12

Masuo Yasui also moved into agriculture. His farming operation reflected his belief in permanent settlement in America. He purchased 320 acres of marginal land, which he offered to a dozen Japanese to cultivate. In exchange for their labor, these Japanese were given a part interest in the farms and orchards so that they could become landowners. Masuo also offered the settlers his financing and management skills.13 Moreover, he showed his fellow Issei farmers the potential of such a new crop as asparagus and inspired them to try their hands at it. With the leadership of Yasui, Japanese asparagus farmers later established the Mid-Columbia Vegetable Growers’ Association which annually shipped 50,000 crates of asparagus to eastern markets. Masuo Yasui also provided large quantities of strawberries and other fruits. On the eve of World War II, ten percent of all the apples and pears in Hood River were shipped from his farms throughout the United States and to Europe. By that time, he owned a total of 880 acres in Hood River and 160 acres in Mosier.14

Although few in number, Japanese immigrants also played a crucial role in the agricultural development of Lake Labish near Salem. In 1909, a former railroad worker, Roy Kinzaburo Fukuda, cleared 100 acres in the area to grow hops. Before long, he found the area most suitable for the production of celery and developed the famous Golden Plume Celery. By 1917, the dry lake was the exclusive settlement of Japanese farmers who cultivated between six acres to 20 acres each. Three years later, Lake Labish had some 30 farms with the population of 58 Japanese.15

Lake Labish Japanese farmers were well-known throughout the country for their superior celery. With Fukuda as the leader, they organized the Labish Meadow Celery Union. In 1925, the union shipped 314 freight cars, of which over 70 percent went to the eastern market. Interested in the fast growth of the farm community and its product, Senator Charles L. McNary of Oregon even paid a personal visit to Fukuda’s farm. In appreciation, Fukuda sent a sample of celery to McNary and to President Coolidge.16 In response, the Senator wrote, “I distributed it among several of my senatorial friends, all of whom pronounced it the most delicious they [have] ever eaten… I took a genuine pride in their commendation.”17 He added that the President also praised the celery. In the 1930s, the growers association increased its shipment to 700 carloads a year.18

Notes:

1. Tachibana Ginsha, Hokubei Haikushu, p. 37.

2. Gaimusho, Nihon Gaiko Bunsho: Tabei IminMondai Keika Gaiyo, p. 375.

3. Nichibei Shimbun-sha, Nichibei Nenkan, Vol. 6 (San Francisco: Nichibei Shimbun-sha, 1910), pp. 203-204.

4. Ibid. p. 203.

5. Marjorie R. Stearns, “The History of the Japanese People in Oregon,” p. 2. In her thesis, she calls the community “Russellville” instead of “Montavilla.” However, the common name that Japanese immigrants usually used to refer to the community was Montavilla.

6. Junichi Torai, Hokubei Nihonjin Soran, pp. 126-133.

7. Frank Davey, Report on the Japanese Situation in Oregon (Salem: State Preinting Department, 1920), p. 5.

8. Nichibei Shimbun-sha, Nichibei Nenkan, Vol. 6, p. 204.

9. Hokubei Jiji-sha, Hokubei Nenkan, Vol.2 (Seattle: Hokubei Jiji-sha, 1911), p. 228; and Nichibei Shimbun-sha, Nichibei Nenkan, Vol. 10 (San Francisco: Nichibei Shimbun-sha, 1914) pp. 158-159.

10. Frank Davey, Report on the Japanese Situation in Oregon, p. 14; Baqrbara yasui, “The Nikkei inOregon, 1834-1940,” pp. 241-242.

11. Letter from Masuo Yasui to Renichi Fujimoto, June 14, 1907, in Homer Yasui Collection. The ideal of permanent settlement was shared with other prominent Issei leaders. In California, for example, Kyutaro Abiko disseminated the ideal through his newspaper, the Nichibei Shimbun. In order to put it into practice, he also purchased a large tract in the central San Joaquin Valley, which he subdivided into smaller parcels for the Issei who intended to settle down as farmers. Before moving to Hood River, Masuo Yasui apparently had studied Abiko’s project as a model.

12. Robert Yasui, The Yasui Family of Hood River, Oregon (Hood River, OR: Holly Yasui, 1987), pp. 6, 10; and Barbara Yasui, “The Nikkei in Oregon, 1834-1940,” p. 241.

13. Robert Yasui, The Yasui Family of Hood River, Oregon, pp. 7-8; Barbara Yasui, “The Nikkei in Oregon, 1834-1940,” pp. 248-249.

14. Hokubei Jiji-sha, Hokubei Nenkan (Seattle: Hokubei-Jiji-sha. 1936), pp. 207-222.

15. Marvin G. Pursinger, “The Japanese Settle in Oregon, 1880-1920,” p. 257; Kojiro Takeuchi, Beikoku Seihokubu Nihon Iminshi, (Seattle: Taihouku Nippo, 1929), p. 885; and Kazuo Ito, Issei: A History of Japanese Immigrants in North America, pp. 513-514.

16. Letter from Roy Fukuda to Chas. L. McNary, October 2, 1925, in Frank Fukuda Personal Collection.

17. Letter from Chas. L. McNary to Roy Fukuda, November 2, 1925, in Frank Fukuda Personal Collection.

18. Ko Murai, Zaibei Nihonjin Sangyo Soran (Los Angeles: Beikoku Gangyo Nippo-sha, 1940), pp. 963-964.

* This article was originally published in In This Great Land of Freedom: The Japanese Pioneers of Oregon (1993).

© 2017 Japanese American National Museum