“It is never too late to investigate the roots. Not to live from the longing for the past, but to understand how that past speaks to us about our present,” says Mexican anthropologist Dahil Melgar.

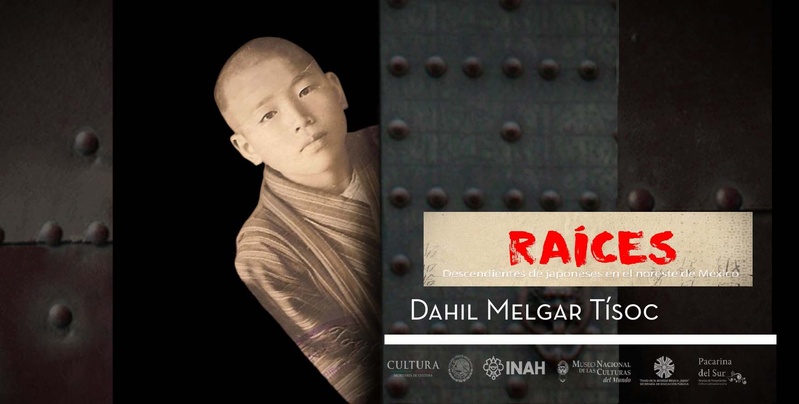

It is never too late, even if 100 years have passed. Dahil demonstrates this in the documentary Raíces , which contains testimonies from Mexican Nikkei about their family history and what it means for them to be descendants of Japanese.

They are stories that could inspire a saga, with its epic and dramatic load, that begins in Japan at the end of the 19th century or the beginning of the next, with Japanese people who go to sea pursuing a dreamed future in distant America, and that It ends in present-day Mexico, with its Mexican descendants reconstructing their history. And in the middle, many things: the arrival of immigrants to Mexico, the settling down in the new homeland, the outbreak of the Second World War and the concentration of Japanese, the reconstruction of the community, the revaluation of Japan as a world power and Nikkei pride.

Stories like that of Ricardo Pérez Otakara, who in the documentary says that he did not know that his grandfather was concentrated during the war or the meaning of the term Nikkei. After discovering his grandfather's story, he decided to found the Mexican Japanese Association of the Northeast.

Dahil offers details:

“His grandfather was an exception to the profile of migrants at the beginning of the 20th century, since he was a first-born male — most migrants were not first-born since they inherited the lands. The Otakara family in Japan transmitted, from one generation to another, the promise of finding the firstborn lost in Mexico. With the passage of time and new technologies, the search became possible. One of his nieces decided to call the Mexican Japanese Association in Mexico City and ask if they knew anything. Locating him was a complex task because the family did not participate in Nikkei community life, but they managed to be located and an interrupted family and cultural bond was reestablished.”

Chance, unintentionally, can play a crucial role in the destiny of a family. In the case of Miguel Ángel Kiyama and his father, it was chance disguised as sport.

“Mr. Kiyama's father lost contact with his family in Japan as a result of World War II. But during the 1968 Mexico Olympics, he was invited to be a translator for a delegation of Japanese boxers who, in gratitude, looked for his family in Japan and helped him reestablish contact. Years later, Mr. Kiyama would travel to Japan to meet them,” says Dahil.

One of the interviewees, Miguel Ángel Romero Ogawa, reveals that he never had any interest in his Japanese origin. He even made fun of one of his sisters for “thinking” she was Japanese. From his immigrant grandfather he knew the Spanish name that he acquired in Mexico, but not the real Japanese name. Not even his mother knew his name.

“Everything changed when one day a woman from the town to which his grandfather migrated searched for him on Facebook and began sharing photos and documents of the Ogawa family,” says Dahil.

In the short, Romero Ogawa shows a letter that his Mexican grandmother wrote to the governor of Sonora to ask him to return her concentrated husband, since he was the breadwinner of the family. “It was heartbreaking,” he confesses. The request found no response.

120 YEARS, THE STARTING POINT

The migration of Japanese to Mexico began 120 years ago. To celebrate the anniversary, various activities were carried out in the country. The anniversary motivated Dahil Melgar to make the documentary. “This commemoration led me to think, what does 120 years of history mean in terms of family memory and identity?”

The answer is Roots . “I wanted to propose an audiovisual story in which Mexicans of Japanese origin, from different generations, would narrate the immigration stories of their families, but above all, their life experiences as descendants.”

His desire was “to show how identity changes and transforms according to historical episodes and personal experiences, and that we cannot speak of a single way of being and thinking as a Nikkei.”

An important actor in this story is the Japanese anthropologist Shinji Hirai, who created a workshop to help Mexicans of Japanese origin delve into their ancestors through documents and family albums. Dahil became particularly interested in the project when he learned that the participants were Nikkei who knew little or nothing about their family history.

The lack of knowledge of the history of their ancestors was influenced, as she points out, by the fact that “until 1924, Japanese migrations were still mainly male. This implied that the first migrants established marriages with Mexican women, and that the education and transmission of culture at home was local. Several of those interviewed remember—either from their own experiences or family stories—their Japanese parents or grandparents as distant, uncommunicative; and they even show surprise at having found photographs that show them sociable, in more playful scenarios of community and festive coexistence. “An image that contrasts with the memory they have.”

As in the rest of the American countries where Japanese immigrants settled, the Second World War was a watershed in the history of the Japanese community in Mexico. The Mexican government, aligned against the Axis countries, established “forced relocation camps for Japanese in the cities of Temixco, Mexico, and Guadalajara. After the concentration, not all the Japanese and their families returned to the towns in which they had settled.”

That the Mexican Nikkei were unaware of the history of their ancestors is also explained by the fact that the concentration of the Japanese during the war became a taboo subject in the community.

THE JAPANESE ORIGIN: FROM STIGMA TO EMBLEM

Anthropologist Shinji Hirai affirms that in the past, especially during the war, being of Japanese descent in Mexico was a kind of disadvantage or stigma. Now, it's like an emblem.

Dahil explains: “It can be said, today more than ever, that pride in Japanese ancestry is at its best. On the one hand, in the last four decades, Japan repositioned itself economically, technologically and industrially; but also in the last two, it capitalized on its manga, anime, fashion, food and music industries.”

Speaking of anime, one of the Nikkei interviewed, Soichi Sakay, remembers that when he was a child he wanted to change his name. He had up to 15 nicknames related to his Japanese name.

Everything changed when works like Sailor Moon and Dragon Ball became fashionable in Mexico. Everything Japanese was cool. Soichi remembers that they once told him: “Hey, your name is Soichi, what a father. I want a name like that.”

Technology has been instrumental not only in connecting the Nikkei to their immigrant ancestors, but also to Japan.

“Third and fourth generation Nikkei are having opportunities to connect to Japan that their parents did not have through virtual platforms that allow them to connect with other descendants in the world, walk the streets of Japan on a virtual level, stay up to date through videos and media production, among other possibilities,” says Dahil.

For the Mexican anthropologist, the story does not stop here. He wants to make a second part, a short film about the meetings of the Mexican Nikkei who appear in Raíces with their families in Japan.

The value of his work is not only because it documents the reconnection of descendants with their roots, but also because it shows how those who were disconnected or whose connection was weak, by discovering their family history, also begin to be part of a community. , generating a strong sense of identity and belonging.

Ricardo Pérez Otakara sums it up perfectly, when at the end of the short he says: “My story is the story of many Nikkei. And his story is my story.”

© 2017 Enrique Higa